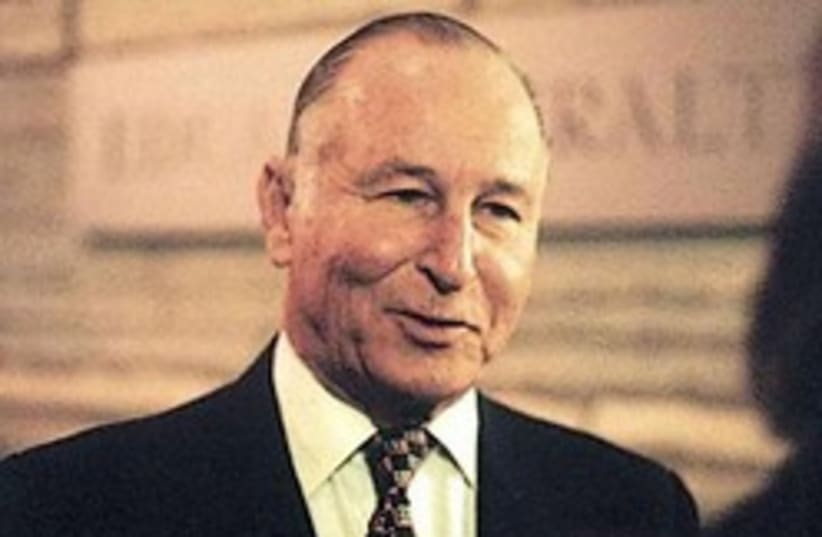

One who got away

An alleged Estonian Nazi war criminal died last week in Costa Rica. This is the story of the thwarted effort to bring him to justice.

Last week, suspected Estonian Nazi war criminal Harry Mannil died unprosecuted in San Jose, Costa Rica at the age of 89.Mannil, who served for the first year of the Nazi occupation in the Estonian Political Police in Tallinn - which was responsible for the arrest and murder of numerous Jews and communists - was ranked No. 10 on the Simon Wiesenthal Center's most recent "Most Wanted" list.His case came to my attention in the early 1990s as a byproduct of the investigation of his superior, Evald Mikson, a notorious murderer and rapist, whom I exposed living in Iceland and who died suddenly after the local authorities opened up a murder investigation against him.Mannil escaped after the war to Venezuela, where he became a multimillionaire. This is the story of our efforts to bring him to justice.The Evald Mikson case was not our only investigation that related to Nazi war crimes in Estonia, but it is of special significance for two reasons.The first is that it clearly reflected the ambivalent attitude of the Estonian government to the issue of local Nazi collaborators. On the one hand, I was granted access to the KGB files, where I found extremely incriminating testimony against Mikson. On the other hand, if I recall correctly, the Estonian Foreign Ministry issued an official statement that asserted that Mikson was not guilty of any crimes, and least of all against the Jewish people, a total distortion of the historical facts.A second reason for the case's significance is that it led me to two additional suspects who had worked under Mikson in the Estonian political police - Martin Jensen, who had immigrated to Toronto, Canada, and Harry Mannil, who had escaped to Caracas, Venezuela.Jensen died on August 8, 1992, not long after I had notified the Canadian War Crimes Unit of his presence in Toronto. Mannil was still alive, and his case proved to be one of the most difficult I ever dealt with.In theory, everyone is supposed to be equal in the eyes of the law, but being one of the richest Estonians in the world and a generous donor to Estonian cultural institutions apparently can help protect a suspected Nazi collaborator from prosecution in Estonia. Thus, all our efforts to facilitate the prosecution of Mannil for his alleged role in the arrests and interrogations of Jews who were murdered by the Nazis and their Estonian collaborators were unsuccessful.Part of the problem stemmed from the fact that we were never able to prove that Mannil personally committed murder. While there was testimony recorded by the Sandler Commission (which investigated the Baltic refugees who escaped to Sweden) that Mannil had killed as many as 100 Jews, we were unable to corroborate this accusation.Still, over the years, we were able to record several victories against him. For example, I made sure that he was put on the American watch-list of individuals barred from entering the United States because of their purported Nazi past. Mannil was actually kicked out of the country upon arrival at a Florida airport at least once. (The list is secret and he had no idea that he was on it.)Another victory was the resignation of Henry Kissinger from the board of the Baltic Institute for Strategic and International Studies, which Mannil established in Tallinn. After I brought Mannil's past to the attention of the former secretary of state, he resigned from the board on January 24, 1994, and thanked me for informing him of the matter and bringing the relevant documentation to his attention.A third such victory, which was unfortunately shortlived, was Mannil's expulsion on February 4, 2003, from Costa Rica, where he had business interests and often visited, because according to the immigration director Marco Badilla, "His presence could compromise national security, public order, or way of life."Nine months and three days later, however, Badilla secretly rescinded his original order, allowing Mannil to reenter the country.In early 2001, I decided that our best bet to bring Mannil to trial was to try to convince the Estonians to do so. That summer, I met with the Estonian prime minister Mart Laar in Tallinn to discuss the possibility that the Estonians would open an official investigation against Mannil and to persuade him to seek the assistance of the OSI (the US Justice Department's Office of Special Investigations), which I understood had obtained new documentation in the case.The investigation was eventually opened, but the visit, my first to Estonia in almost a decade, was marred by several ugly run-ins with the local media. In the course of an interview with the Estonian daily Eesti Paevaleht, I was asked whether any Estonian civilians had murdered Jews during the Holocaust. I answered in the affirmative, noting the murders carried out by the Omakaitse during the initial weeks following the Nazi invasion.Imagine my consternation the next morning when someone translated the headline of the interview. It read, "Nazi-hunter Accuses Estonian Nation of Murders" - precisely the type of assertion that, besides being patently false, was certain to infuriate Estonian public opinion and increase its opposition to the prosecution of Harry Mannil and any other suspected local Nazi war criminals.Another manifestation of the deep-seated local resistance to my efforts to hold Estonian murderers of Jews accountable was the most offensive caricature of me ever published anywhere, which appeared in the August 23, 2001, issue of Eesti Ekspress, Estonia's most popular weekly newsmagazine.It portrayed me as the devil, complete with horns, and holding a pitchfork upon which were impaled several discs with swastikas on them. In my other hand, I was holding a cup emblazoned with the inscription "Wiesenthal Keskus" (Center), into which prime minister Laar was seen pouring Harry Mannil's blood. The caption read, "Kutsumata Kulaline" ("Unwanted Guest").A year later I clashed with the Security Police Board, the agency responsible for the investigation of Estonian Nazi war criminals. In 1998, Estonia, like its Baltic neighbors, had established an International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity, which was mandated to examine all crimes committed under the Communist (1940-1941; 1944-1991) and Nazi (1941-1944) occupations of Estonia.One of the surprising initial findings of the commission, which was published in 2001, was that on August 7, 1942, the 36th Estonian Security Police Battalion participated in the mass murder of the Jews of Nowogrudok, Belarus.Several months later, based on this information, I submitted to Juri Pihl, the director-general of the board, a list of 16 members of the unit who had been awarded the Iron Cross second class by the Nazis in December 1942 on the assumption that those decorated might have excelled in the murder of Jews.Less than two weeks later, the board informed the media that they had no information regarding the participation of the 36th Battalion in the murder of the Jews of Nowogrudok, a direct contradiction of the findings of the Estonian international historical commission.I used this example in an op-ed piece I published in Eesti Paevaleht on August 7, 2002, the 60th anniversary of the murders, to demonstrate how Estonia was not facing its Holocaust past, and urged the government to designate a day to commemorate the annihilation of European Jewry.A date was decided on that same day, but the date chosen was January 27, the day of the liberation of Auschwitz, which, considering the fact that no Estonian Jews had been deported to that camp, only strengthened the opinion of many Estonians that there was no connection between their country and the Holocaust. An opinion poll held right after the decision confirmed the problem. Ninety-three percent of those polled opposed a Holocaust memorial day in Estonia.In the conclusions of the International Commission, there was an unequivocally negative evaluation of the activities of Evald Mikson, who was "particularly singled out," along with six other Estonian Nazi collaborators, as being "actively involved in the arrest and killing of Estonian Jews."He and three others - Ain-Ervin Mere, Julius Ennok, and Ervin Viks - were named as the ones who "signed numerous death warrants." Not that these findings in any way convinced his children that their father had done anything wrong during the war.As far as Mannil is concerned, as could be expected, the investigation was finally closed by the Security Police Board on December 30, 2005, after several years of investigation, with no charges brought against him.What made this decision particularly infuriating was that the Estonian investigation confirmed not only that Mannil had worked for the dreaded Estonian political police, but that at least seven persons (all named) whom he had arrested and interrogated had been executed by Estonian Nazi collaborators. This confirmed an important component of our original accusations, albeit with the exact opposite conclusion.In other words, those findings would have almost certainly been sufficient to have Mannil prosecuted in any country that treats Holocaust crimes seriously, but clearly Estonia is not such a country.Excerpted and adapted by Efraim Zuroff from his book Operation Last Chance. Copyright © 2009 by the author and reprinted by permission of Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved.

if(catID != 151){

var cont = `Take Israel home with the new

Jerusalem Post Store

Shop now >>

`;

document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont;

var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link");

if(divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined')

{

divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e";

divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center";

divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "40px";

divWithLink.style.marginTop = "40px";

divWithLink.style.width = "728px";

divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#3c4860";

divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff";

}

}

(function (v, i){

});