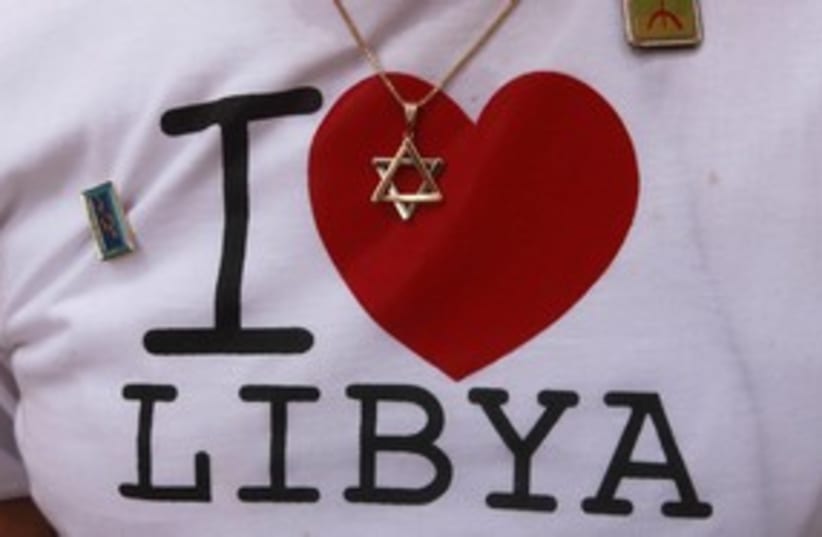

Libyan Jews abroad deeply ambivalent about uprising“I did what I had to do to raise the issue and see what kind of a country this will become.”On Saturday, Gerbi showed up at the city’s abandoned central synagogue wearing an “I heart Libya” T-shirt and carrying a sledgehammer. He broke through a wall sealing the Jewish place of worship and told reporters he planned to reopen it to prayers.But when he returned the following day he was greeted by a group of armed men with assault rifles warning him his life was in danger. The door was locked and neighbors who had previously expressed support warned him to stay away.“It’s not the right time for this,” one of them was quoted by National Public Radio as saying. “It’s a very sensitive matter. We appreciate having different religions in our country. We want that. But not at this time.”Back at his hotel room, Gerbi was angry at those who barred him from returning to the temple.“I was told I was abusing an archeological building. This is the place where my uncle is buried,” he said.Gerbi’s initiative and its failure made headlines around the world. Meir Kahlon of the World Organization of Libyan Jewry, a diaspora group based in Israel, hailed his efforts for raising awareness to the rights of Jews exiled from Libya, while others, including the National Transitional Council, said they were provocative and premature.“The fact that he can move around freely is an indication of how Libya has changed,” a spokesman for the NTC was quoted as saying. “The NTC is a temporary body and isn’t prepared to deal with this sensitive issue right now.”Gerbi even came under fire from other members of the Libyan Jewish diaspora, which numbers about 200,000 people living mostly in Israel and Italy.“Anyone really interested in finding a collective negotiated solution on the Jewish-Libyan question would do well to refrain from seeking personal results and return to the ranks of the Jewish community,” wrote Elio Racch, a member of the coordinating committee of the Libyan Jewish diaspora in Italy.But Gerbi, who left Libya with his family at the age of 12 because of state-sanctioned anti-Semitism that emerged in response to the Israeli-Arab conflict, said he had waited long enough.“The Libyan government needs to prove it is not anti-Semitic and justify the support from the US and Europe,” he said.Regarding his critics from within the Libyan Jewish diaspora, he rebuked them for not returning to the country in person like he did.“They can speak from there and have their opinions but they don’t know what the reality is like here,” he said. “Only by being here and being part of the revolution I have respect. Why aren’t the people of Libya on our side? They ask. Why are they so indifferent? They think we don’t exist, that we don’t support them.”In hindsight he admitted he had not expected the backlash over his attempt to reopen the dilapidated synagogue, but said he was glad he tried.“I’m going to stop now and start to talk but it transformed the issue,” he said. “I thought the reopening was going to be a happy end and there’d be a Jewish delegation coming over to do a kadish [mourner’s prayer], but it didn’t happen like that.”

Libyan Jew demands new regime tackle anti-Semitism

David Gerbi to 'Post': Failed bid to reopen synagogue in Tripoli has transformed debate on rights of Jews in country.

Libyan Jews abroad deeply ambivalent about uprising“I did what I had to do to raise the issue and see what kind of a country this will become.”On Saturday, Gerbi showed up at the city’s abandoned central synagogue wearing an “I heart Libya” T-shirt and carrying a sledgehammer. He broke through a wall sealing the Jewish place of worship and told reporters he planned to reopen it to prayers.But when he returned the following day he was greeted by a group of armed men with assault rifles warning him his life was in danger. The door was locked and neighbors who had previously expressed support warned him to stay away.“It’s not the right time for this,” one of them was quoted by National Public Radio as saying. “It’s a very sensitive matter. We appreciate having different religions in our country. We want that. But not at this time.”Back at his hotel room, Gerbi was angry at those who barred him from returning to the temple.“I was told I was abusing an archeological building. This is the place where my uncle is buried,” he said.Gerbi’s initiative and its failure made headlines around the world. Meir Kahlon of the World Organization of Libyan Jewry, a diaspora group based in Israel, hailed his efforts for raising awareness to the rights of Jews exiled from Libya, while others, including the National Transitional Council, said they were provocative and premature.“The fact that he can move around freely is an indication of how Libya has changed,” a spokesman for the NTC was quoted as saying. “The NTC is a temporary body and isn’t prepared to deal with this sensitive issue right now.”Gerbi even came under fire from other members of the Libyan Jewish diaspora, which numbers about 200,000 people living mostly in Israel and Italy.“Anyone really interested in finding a collective negotiated solution on the Jewish-Libyan question would do well to refrain from seeking personal results and return to the ranks of the Jewish community,” wrote Elio Racch, a member of the coordinating committee of the Libyan Jewish diaspora in Italy.But Gerbi, who left Libya with his family at the age of 12 because of state-sanctioned anti-Semitism that emerged in response to the Israeli-Arab conflict, said he had waited long enough.“The Libyan government needs to prove it is not anti-Semitic and justify the support from the US and Europe,” he said.Regarding his critics from within the Libyan Jewish diaspora, he rebuked them for not returning to the country in person like he did.“They can speak from there and have their opinions but they don’t know what the reality is like here,” he said. “Only by being here and being part of the revolution I have respect. Why aren’t the people of Libya on our side? They ask. Why are they so indifferent? They think we don’t exist, that we don’t support them.”In hindsight he admitted he had not expected the backlash over his attempt to reopen the dilapidated synagogue, but said he was glad he tried.“I’m going to stop now and start to talk but it transformed the issue,” he said. “I thought the reopening was going to be a happy end and there’d be a Jewish delegation coming over to do a kadish [mourner’s prayer], but it didn’t happen like that.”