See the latest opinion pieces on our page

The odds are very good that one small party will have the power to make – and break – the next government. Such a configuration – which of necessity means bringing together parties that are natural rivals with leaders who can’t stand each other – is unlikely to be much more stable than the last government, which lasted only two years and accomplished nothing.In a January campaign speech, Netanyahu said, “We are splitting into little parties none of which can lead the state, and this problem is getting worse. In the last 66 years since the establishment of the state there have been 33 governments – that comes out to an average government lifespan of less than two years. This has cost us billions, not just in election costs but as a result of the economic uncertainty and the lack of governability.”Responding to the recent election results in an article in The New York Times, Yohanan Plesner of the Israel Democracy Institute said the results show the need for electoral reform because Israel’s “system is so fragmented, so unstable, so difficult to govern.”Instability is not the only problem that the current system causes. Of equally great concern is the out-sized power the system gives to small parties. The haredi parties have often benefited from this – securing laws and funding for their constituencies at the expense of everyone else because they are often the kingmakers in a coalition.In essence, our current electoral allows small parties to blackmail the large parties. Many proposals have been floated to fix the problem. Some say all we have to do is keep increasing the threshold to get into the Knesset.Avigdor Liberman of Yisrael Beytenu managed to push through a law increasing the threshold from 2 percent to 3.25% (at the time of the founding of the state it was 1%). I wonder if he still thinks that was a smart move, as the people he was trying to hurt (the Arabs) unified and turned out in droves, increasing their influence, while his own party struggled to make it past the new threshold.Increasing the threshold in the past hasn’t contributed to stability, and there’s no reason to believe doing the same thing again would solve the problem. Even with a 5% threshold you could have a lot of parties around the six- or seven-seat mark. Even a 10% threshold, as they have in Turkey, could just mean there would be temporary alliances that fall apart quickly after the elections, as many expect will happen with the Joint List.Netanyahu’s proposed reforms are tailor-made to boost his chances of staying in power, and are an undemocratic approach to the problem. He proposes taking away from the president the power to grant anyone but the largest party first crack at forming a coalition, and requiring a super-majority to bring down a government.The first proposal may seem odd coming from him, considering that he was the beneficiary of the president’s discretionary power when he came in second to Tzipi Livni and Kadima in 2009. The super-majority requirement seems a waste of time, as that would do nothing but preserve a government that was then unable to rule because it didn’t really have a coalition of 61 supporters in the Knesset. But Bibi’s biggest goal has always been staying in power – rather than getting anything done.There’s an additional problem with the current system: lack of individual accountability among MKs. As an American immigrant, one of the things that has always disturbed me about Israeli elections is that you don’t vote for a person, you only vote for a party. I often voted across party lines in America, at least back in the 1980s when it was possible to find centrists in either of the major parties.There is a sense of connection and individual responsibility when you vote for someone who personally represents you. If you don’t like him or her you can always “vote the bum out.” I’m not talking about direct election of the prime minister – we tried that, and it was a disaster. You can’t have direct election of the prime minister unless you completely change the way you govern and go to an American model with a strong executive branch. Such a radical change isn’t going to happen any time soon, and it’s not necessarily advisable.After looking around to see what works in other places, I believe New Zealand has a system we should emulate. They have a unicameral legislature of 120 seats, with half of the seats based on geographical districts, where voters select an individual representative, and half of the seats based on a nationwide proportional party vote, as we currently have. New Zealand has 13 parties, eight of which made it into the last legislature, and its governments generally survive the full three-year term.If this system were applied in Israel, the small parties would be at a disadvantage in the district elections; in any particular neighborhood the odds are that one of the larger parties would prevail. This would strengthen the larger parties and add the sense of individual responsibility that goes with having an individual who represents you and your area in the Knesset. At the same time, smaller parties with a non-geographically concentrated following would still have a chance to have a voice and be heard. Strengthening the large parties would strengthen the Center at the expense of the extremes – which would help the government more closely reflect the will of the people.This is not a new idea in Israel: in 2008 Labor and the Likud co-sponsored a bill that would have set aside 60 Knesset seats for district voting. The bill also would have reduced the cabinet to 18 ministers and raised the electoral threshold to 2.5%. Religious and liberal small parties, fearful of losing their clout, joined forces to defeat the bill.Even though I personally support a small party, I don’t believe the current system is working or is in the best interests of the nation. The best thing that could happen would be for Herzog and Netanyahu to agree to a national unity government, pass this bill, and then call for new elections.The author is a rabbi and entrepreneur who lives in Jerusalem. He is the former chairman of Rabbis for Human Rights.

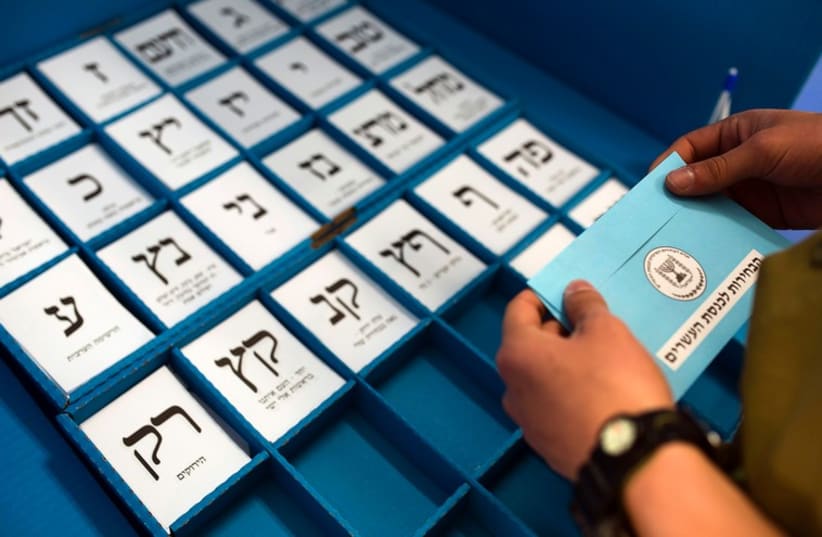

Fixing the electoral system

"The election results lay bare the deep schisms in Israel, the deep polarization, and the fragmented nature of our electoral system."