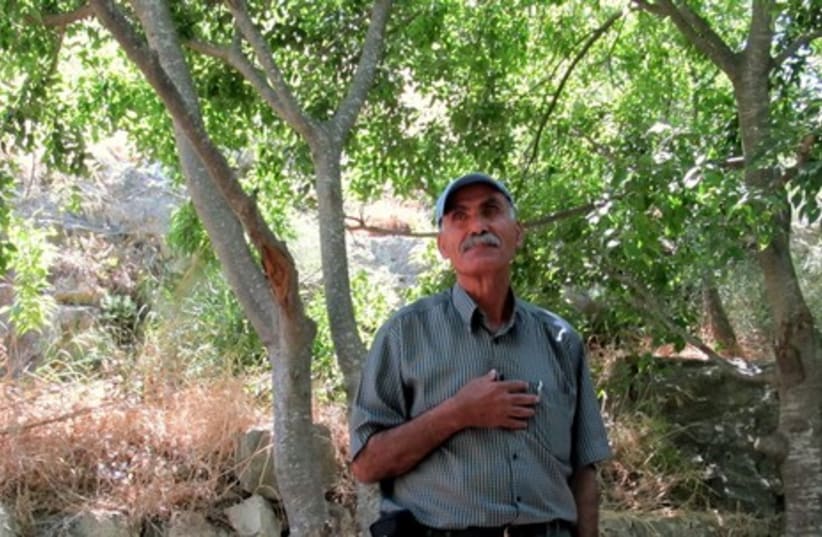

Odeh was eight years old in 1947 when the residents of Lifta, an Arab village at the entrance to Jerusalem, fled. The strategic location of the village, climbing up a steep wadi and stretching towards the Old City, looking down on most of modern-day Jerusalem, meant it was one of the first villages to experience violence leading up to the siege of the city.RELATED:Plans for Lifta luxury housing project temporarily halted Apartments to be built on top of abandoned Arab village Today Lifta is in the middle of a different struggle, one that not only pits Arab history against Jewish history, but delves into the question of how much the city needs to preserve as it grows and develops.In January, the Israel Lands Authority published a tender to build 212 luxury apartment villas and a hotel in the area of Lifta, turning the crumbling stone houses into lavish residences.A coalition of activists successfully petitioned the Jerusalem District Court to halt the tender in March. The petition, filed by former Lifta residents, Rabbis for Human Rights, and Jafra, a Palestinian heritage organization, calls for the courts to freeze the bidding process and for the ILA to require that an independent monitoring organization complete a survey of the area to determine what should be preserved and what can be developed.The activists argue that contractors performing a survey of the land, as is currently required, will be inadequate since the contractors have a commercial interest to preserve as little as possible. The court granted a temporary freeze until a trial is held to determine if the ILA can move forward with the bidding process. The court date at the Jerusalem District Court, which has been delayed by more than two months, is now set for July 7.But the current legal impasse seems miles away from the peacefulness of Lifta, which has stood abandoned but largely intact for 64 years. It is the only completely abandoned Arab village that was not destroyed or inhabited by Jews after 1948, though its empty buildings have provided a haven for drug dealers, prostitutes and the homeless.The stone pool in its center has become a popular mikve ritual bath for haredi men, who spend summer Fridays lounging in the sun and barbecuing.Jerusalem hikers have long delighted in the narrow paths that wend their way between crumbling stone buildings with tall weeds growing out of the cracks, and the quiet island of untamed greenery surrounded on three sides by highways.Odeh remembers a different Lifta, with a garden next to the pool that had strawberry plants up to his waist and neighbors who planted blooming cactuses for fences. He can still remember how his grandfather’s house, perched up high on one side of the wadi, served as the perfect spot for the muzzein’s call. When his grandfather called the community to prayer five times a day, his voice would echo through the canyon, slicing through the quiet of the sleepy agricultural village.Lifta has been inhabited since the First Temple Period, and isone of the original suburbs of Jerusalem’s Old City, along with Malha and Ein Karem.Like many Arab homes, the houses were living beings that tended to expand as the family grew, climbing into the hillside to three or four or five stories. In some houses, the massive stones from the Crusader period are topped by roughly hewn stones from the Ottoman period, and a ceiling with steel reinforced support beams from the time of the British Mandate.Historical Lifta reached from Mevaseret Zion to the walls of the Old City, said Odeh, an expansive 100,000 dunams (10,000 hectares) that was home to 3,000 people and had 600 houses. “Old Lifta” is the part that travelers on Highway 1 see upon entering the capital, though there are still a few original Lifta houses near the Hyatt hotel in Sheikh Jarrah.A quarter of Lifta’s land was terraces of fruit trees, and there was 1,500 dunams of olive trees. “Olives were like petrol today,” said Odeh. The village’s olive presses, which are still intact and visible, as well as the proximity to the major commercial center of the Old City, made the village one of the wealthiest in the area.The descendents of the original nearly 3,000 residents of Lifta now number more than 20,000 and have spread to locations across east Jerusalem, the West Bank, Jordan and Europe.Odeh lives in the French Hill neighborhood with his family, though he visits Lifta nearly every week.For Odeh, the question of Lifta’s development is political: It should return to the Palestinian refugees, many of who added the suffix al-Liftawi to their names to denote their connection to the land.“We are in a campaign to prevent project 6063, to build 212 villas and a hotel and a museum,” he said. “To change Lifta for a colonial resort means to remove it, not to preserve the houses you used to see.”“My memories and my history are linked to Lifta and these houses, the graveyards and the spring water... All of these things are my memories and I’ll never forget them. And I also teach my kids that Lifta was an eyewitness for the Nakba [the “disaster” in 1948] and an eyewitness for history,” he added.A coalition of activist groups has formed to save the complex.Rabbis for Human Rights, Jafra and Zochrot, a Tel Avivbased NGO whose aim is to promote awareness of the Palestinian Nakba, are leading monthly tours of the site to raise awareness about the possible loss of the last Palestinian village left unchanged from before 1948.“It’s going to be a terrible message for the Palestinians and the world that basically we’re continuing what we started in ’48,” Eitan Bronstein, spokesman for Zochrot, said when the tender was announced in January.Both the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel and the Council for the Preservation of Historic Sites favor the development of Lifta.Isaac Shweky, the director of the council, takes a pragmatic approach to Lifta’s development: The site is in desperate need of repair, and if nothing is done it will continue to crumble away and eventually be reduced to nothing, as the weeds and vandals reclaim all 54 of the remaining structures. The cost to preserve the buildings would be astronomical, in the hundreds of millions of shekels. The only way to fund the preservation of the buildings, he believes, is to develop the site commercially.“Every day that goes by the buildings are being destroyed as time takes its toll,” he said.“There are a lot of people who are totally against the project. They want this to be Macchu Picchu of ‘occupied Arab lands.’ They want everyone to see how an Arab village used to be, but that isn’t true, what you see today is just what’s left,” said Shweky, pointing out that the 300 plus homes in the wadi next to Highway 1 have been whittled down to just 54.Empty buildings fall apart with time, he said, and what nature doesn’t reclaim, vandals will.Nearly all of the ornate metalwork has been stolen from the homes, and squatters have destroyed the traditionally decorated tiled floors.Wall paintings are covered by graffiti, as are many of the buildings.Shay Farkash, a Lod-based expert in uncovering wall paintings from old, ruined buildings, was astounded by the number of homes where he could uncover wall paintings and stencils in Lifta. “This is one of the best preserved domes I’ve seen,” he said, using a special scraper to remove decades of grime in a small prayer room that is now home to a squatter, who was absent at the time.“Lifta is one of the last places like it... It’s a magical corner of Jerusalem,” he said. Like Shweky, Farkash agreed that paying the enormous costs of restoration would only be possible through commercial development.The high cost of preservation, which is much more expensive than building a new home from scratch, means the 212 apartments will be very expensive, out of reach of most Israelis. The complex runs the risk of becoming a “ghost town” owned by foreigners who use the apartments once or twice a year. But the construction of the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv high speed train may dampen the uniqueness of the future luxury village, with several trains an hour rushing in and out of tunnels dug deep into the rolling hills next to Highway 1.Both activists and preservationists seem resigned to the fact that some kind of building is inevitable.Shweky said that he preferred that the construction be done now, in a carefully planned way, rather than keeping the site empty and run the risk of having it haphazardly developed in 50 or 60 years when Jerusalem completely runs out of housing options.In the quietness of Lifta on a Friday morning, the rush of the highway traffic is barely audible over the chirping of birds and the sound of the wind through the grass. It’s difficult to picture trains, or luxury apartments, or anything but the silent stone buildings that have stood witness to war and bloodshed and difficult chapters of history.Standing next to the pool, Odeh points towards a house 20 meters up the hillside.“This was the house of Hashan Ali Bedeem,” he recalled. “This house was filled with flowers, beautiful flowers all up the stairs. We would try to steal the flowers, but his mother would catch us,” Odeh laughed. “She would say to us ‘kids, okay, go on, you can smell it [on the vine]. But if you cut it off, then what will you have tomorrow?’”