Until forced to evacuate their homes during Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, farmers from Kibbutz Beit Ha’arava tilled barren, saline soil just north of the Dead Sea. On occasion they would journey to Ein Fash’ha, on the seashore, and wash the grime off their exhausted bodies in its restorative waters.

Eleven bridges altogether were destroyed during the operation, part of a protest against the British policy of strangling Jewish immigration. After the blast, which was executed under heavy fire, Palmah soldiers managed to reach Ein Fash’ha and hide out in the oasis’s wild brush.

Ein Fash’ha fell into Israeli hands during the Six Day War. Recognizing its unique and special qualities, Israeli authorities declared it an official nature reserve and renamed it Einot Tzukim (Cliff Springs).

Next they closed off the northern and southern areas to preserve the region’s plant and animal life, and opened the middle section to the public.

In 1986 the Nature Reserves Authority leased our peaceful retreat to a private company that lost no time in wrecking its aura — to say nothing of its natural assets. Soon the air was filled with smoke from a multitude of barbecues and thousands of cigarettes; loud Mizrahi music boomed all day long throughout the reserve, and the place became as noisy and crowded as a shopping mall. Because people were careless with their fires, the reserve suffered frequent, devastating conflagrations. We stopped coming, of course, and so did other nature lovers.

Fortunately, the company went broke a few years ago and the Nature Reserves Authority — now the Nature Reserves and Parks Authority — returned to Einot Tzukim in 2000. Logically, people these days should be flocking to the reserve, just as they did in the past. But most folks don’t realize that tranquility once again reigns at Einot Tzukim.

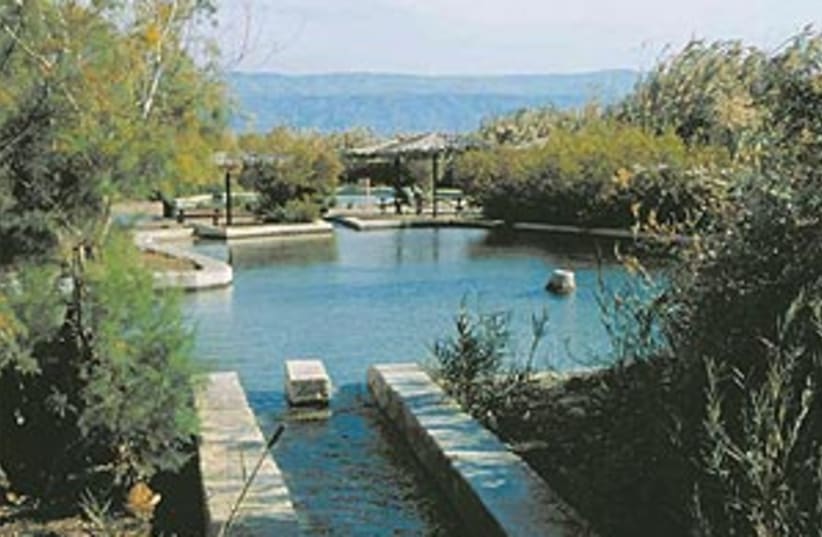

Erez Baruchi, the site’s 27-year-old director, is using every ounce of his youthful energy to return the public to the site. Inviting pools with constantly flowing water are full of minerals believed to have wonderful therapeutic properties. The springs are lined with tall, refreshing foliage; restrooms, showers and picnic tables are clean and in good repair.

There are even some new attractions at the reserve. Baruchi and his tiny staff toiled for over a month to clear weeds and masses of debris off historic ruins dating back 2,000 years. Boasting fascinating artifacts, a well-preserved staircase, a decorative entrance and the largest installation for preparing balsam oil (the talmudic afarsemon) in the country, this Herodian-era estate was excavated in the mid-1950s and then all but forgotten.

Sadly, the Dead Sea has been steadily shrinking for decades and there is no longer a beach at Einot Tzukim. Beach-type pleasures have been replaced, instead, by treks into what rangers call the ’hidden reserve.’ A wilderness that is three times as large as the public area, this well-concealed jungle is not visible from the highway and in the past was effectively closed to outsiders. Indeed, until recently few people were aware of its existence.

Baruchi opened the hidden reserve to visitors and provides them with accompanying guides. People who come for the guided tours are often surprised to find that Einot Tzukim is actually the Ein Fash’ha of earlier times! Delighted to have returned to the site, they enjoy the hidden reserve and spend the rest of the day at the pools and springs.

One sunny December morning, when the air was crisp and cool, we joined Baruchi for a guided tour of our own. Walking through a wonderland of jungles and sparkling streams, we delighted in the sound and sight of water tumbling over rocks. Like thousands of visitors before us, we were reminded of the Tel Dan Nature Reserve in Galilee. Scattered here and there throughout the reserve, majestic palm trees provide a striking contrast to other foliage. None of the trees were planted here. Instead, rangers assume that they stand where date-loving jackals and birds left droppings full of date seeds.

Wild animals roam the reserve at night after everyone goes home.

Rangers have actually seen the jackals, says Baruchi, and have been able to identify tracks belonging to wolves, foxes, hyenas, and leopards. During the day, however, the only mammals you see here are donkeys, brought here nearly two decades ago to devour some of the reeds.

Baruchi explained that in the aftermath of a fire, of which there were so many in the past, reeds dominate the reserve. They multiply so rapidly that they cast a shadow over the landscape and prevent the growth of other flora.

Initially, nature experts thought goats could control their spread. But the goats ate everything in sight, got terribly upset stomachs and had to be removed. Camels were next, but they blindly follow a leader and would trample over a spot, crushing the foliage.

Donkeys were a last resort but they, too, are unsatisfactory and most have been removed. Those who still roam the reserve eat the wooden bridges and the legs on the wooden watchtower, and are slowly killing off one of the reserve’s most interesting natural residents, the weaving ant.

Weaving ants subsist on a honeydew that is secreted by cicadas, which drink sap from the tamarisk tree, absorb its protein and excrete its sugar. Weaving ants protect their source of supply by building shelters for the cicada young to shade them from the sun and prevent birds and insects from devouring them. Ants even accompany the baby cicadas when they leave their shelter to gather food.

So what is the connection with donkeys, you ask? Donkey droppings apparently contaminate the ground on which weaving ants live in summer, and the result has been a significant drop in the weaving-ant population.

We were strolling along a path lined with masses of bulrushes, reeds, saltbush, and tamarisk trees when we ran smack into a clear blue lake surrounded by tall green foliage. To our surprise, we could see freshwater fish swimming merrily to and fro in its salty waters.

The explanation was simple: Sometime before the Six Day War, the late King Hussein of Jordan took a trip to the Dead Sea’s northern shore. He was so enchanted by Ein Fash’ha that he vowed to turn the oasis into a luxurious desert spa. In the meantime, he asked a good friend from east Jerusalem to keep an eye on this precious find.

Captivated by the sight of the shimmering lake and apparently unaware of its saline quality, the friend decided to stock the waters with St. Peter’s fish. Strangely, although lighter in color and much smaller than those in the sweet waters of the Kinneret, the fish have adapted well to their new environment.

On our way back to the open reserve at the end of our tour, we saw a bizarre and disturbing sight. Several hundred meters of desolate brown bog, once under water, stretched from where we were standing all the way to the sea. Now we understood why Einot Tzukim doesn’t have fixed dimensions: since the reserve is bordered to the east by the ever contracting Dead Sea, it grows proportionately larger every year.

Finding the hidden reserve

You might prefer to wander the ’hidden reserve’ without a guide in tow.

But rangers are very adamant about the need to protect this stunning oasis — indeed, there hasn’t been a single fire since nature authorities returned to the reserve. Besides, the guides answer questions and show you all kinds of phenomena you might otherwise miss — like the small praying mantis that site director Erez Baruchi pointed out on one of the trees.

Tours almost always take place at noon on Saturdays, and generally at other times of the day as well. Nevertheless, it pays to call before you come to make sure that nothing has changed.

Guides are more than happy to take you through the ’hidden reserve’ during the week as well. Call first to set up a time: if possible, come as part of a small group of friends. Although tours are in Hebrew, English-language tours can be arranged. There is no extra charge. Phone: (02) 994-2355.

How to get there: Ein Fash’ha is near the northern tip of the Dead Sea, across from Qumran National Park on the Arava highway (Route 90).

Bus 486 or 487 from Jerusalem.

Hours:

Winter: Saturday-Thursday 8 to 4; Friday to 3. Summer: Saturday-Thursday 8 to 5; Friday to 4.

Entrance: adults NIS 25; children five-18 NIS 12. Under five, no charge.

| More about: | Hussein of Jordan, Saint Peter, Qumran, Allenby Bridge |