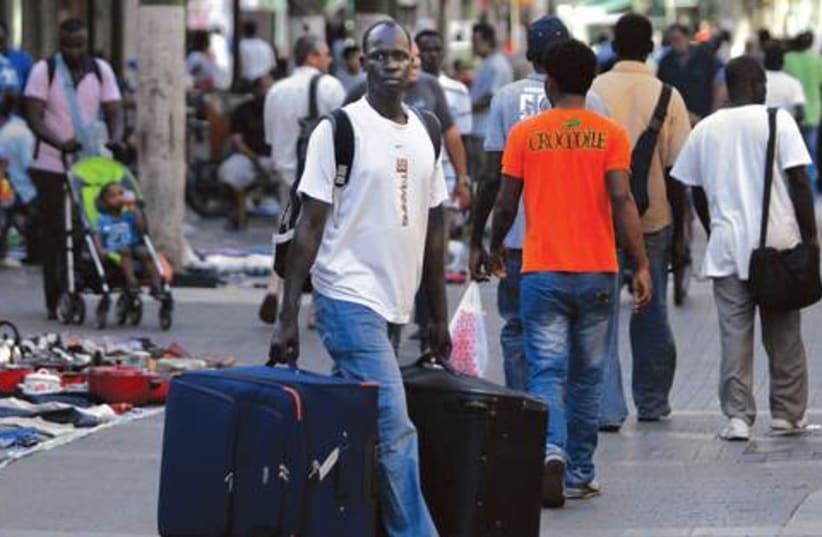

What rankles almost as much as Israel’s erratic treatment of African asylum seekers is the callous ignorance of some its leaders. No one at all familiar with Jewish history would call displaced persons “purveyors of disease,” as Interior Minister Eli Yishai did, or claim with Likud lawmaker Miri Regev that they are “a cancer in our body.”Not surprisingly, these inflammatory statements triggered hate crimes against asylum seekers in south Tel Aviv and elsewhere in June.Although the government was quick to condemn the violence, for many it was guilty on at least two counts: Not doing enough to stop the incitement and pursuing a confused policy on refugees.In an angry letter to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, a group of leading intellectuals accused him of hiding “behind the street” and “behind coalition members inciting in the style of the 1930s.”William Tall, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in Israel, also blamed the government for the continuing unrest in the poorer urban areas where the asylum seekers live. In his view, by calling asylum seekers “infiltrators” and implying that it could deport them all in double quick time, when it knew that the vast majority had been granted collective immunity and could not be repatriated, the government was creating unrealistic expectations that would blow up in its face.Of the 60,000 asylum seekers in Israel, around 50,000 or 83 percent are Eritrean or Sudanese. In 2008, at UN insistence, Israel granted both groups “collective immunity.”This meant undertaking not to return them to their home countries as long as this put their lives at risk. But, in a move opposed by the UN, Israel took this collective undertaking as a license to stop processing individual applications for refugee status, with attendant residency rights. The thinking was to keep members of both groups in a limbo status so that they could be repatriated en masse as soon as conditions in their home countries permitted.Social disaster The result was social disaster: Around 50,000 asylum seekers in Israel who cannot be deported, but cannot legally work because their temporary residency permits don’t allow it, have no access to social services or non-emergency medical treatment and cannot receive international aid because they are not classed as refugees. Draconian legislation in January and early June made matters worse: The threat of heavy fines and long jail terms frightened away people who had been employing asylum seekers illegally.The policy has left huge concentrations of unemployed asylum seekers eking out whatever subsistence they can in poor urban areas like south Tel Aviv and inevitably clashing with local residents falsely led to believe that the newcomers would soon be deported.The government’s answer: detention facilities near the Egyptian border. This would take the asylum seekers off the streets, house, clothe and feed them until deportation opportunities presented themselves.But there are two gaping holes in the plan.The detention facilities will be able to hold 15,000 asylum seekers at most. What about the other 45,000? How are they supposed to fend for themselves? Moreover, indefinite detention of asylum seekers without processing their individual applications for refugee status violates international laws ratified by Israel.After the Holocaust, Israel was one of the initiators of the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which it ratified in 1954. But although it also accepted the additional protocols in 1968, it never incorporated the convention into domestic law. As a result its asylum policies are governed by Interior Ministry regulations enforced by the ministry’s Population, Immigration and Borders Authority.On the face of it, three aspects of these regulations and consequent Israeli practice violate the UN convention: failure to consider individual eligibility for asylum; failure to provide asylum seekers with social, health and employment rights while their applications are processed; and indefinite detention of asylum seekers.To this Israel added two draconian laws that clearly contravene the convention. In January, the government quietly adapted a 1954 antiinfiltration law against terrorists to apply to all those illegally crossing the border, enabling detention of asylum seekers for up to three years. In June, a new law imposed up to five years in jail and fines of up to $1.3 million on people who employ them.Israel has not always taken such an uncompromising stand. In 1977, it was among the first countries to welcome Vietnamese refugees.Between 1977 and 1979, it took in over 300 Vietnamese “boat people.”“We have never forgotten the boat with 900 Jews, the St. Louis, having left Germany in the last weeks before the Second World War…traveling from harbor to harbor, from country to country, crying out for refuge,” declared Prime Minister Menachem Begin, displaying a sense of Jewish history some of his successors seem to lack.Some argue that the fervor with which Interior Minister Yishai is acting against today’s asylum seekers stems from a hidden economic agenda. They charge that companies bringing in foreign workers for a fee make at least $10,000 per worker. Every asylum seeker who takes a job means one foreign worker less and a $10,000 loss to one of around 160 manpower companies, some of which are said to have close ties with Yishai’s Shas party.In June, Yishai began targeting South Sudanese asylum seekers, after a ruling by a Jerusalem Court that South Sudan, after gaining independence, was no longer dangerous.The South Sudanese were offered resettlement stipends if they accepted voluntary repatriation, 1000 euros for adults, 500 euros for minors. If they didn’t, they would be rounded up and expelled empty-handed.The number of South Sudanese is estimated at barely 1,000. So that even if they are all repatriated, it will make only a tiny dent in the numbers. Moreover, in summarily expelling South Sudanese who refuse to go voluntarily, Israel would again be contravening the strict letter of the law. According to UN procedure, it is legally bound to first consider their individual asylum applications.Part of the problem is that the refugee status determination process is log-jammed. In 2009, it was transferred from the UN High Commission for Refugees to the Interior Ministry, where there are only 14 officials handling tens of thousands of applications.The heady brew of insensitive government policy, incitement and violence has played into the hands of Israel’s detractors. It has also hurt Israel’s image in the US, especially among Afro-Americans.Israel would be much better off allowing asylum seekers their full rights: legal permission to work as well as access to social and health services while their asylum applications are processed efficiently and according to clear guidelines.To keep the numbers down to manageable proportions, it could take a few internationally acceptable steps: • Complete the 150 mile fence along the porous Egyptian border, which asylum seekers have been crossing in growing numbers.• Cut the number of foreign workers brought into the country by the number of asylum seekers in work. In 2009, Israel brought in 120,000 foreign workers, compared to just over 4,000 asylum seekers.• Have a fixed refugee quota, something like opposition Labor leader Shelly Yachimovich’s proposal that no more than 2,000 asylum seekers can be granted refugee status each year.New legislation sponsored by the Kadima Party seeks to address the overall question of migration to Israel. It seems to be going in the right general direction: Making it difficult for migrants to get into Israel, but granting them full social, employment and temporary residency rights once they do, and instituting tough but clear criteria for permanent residency.