| More about: | Tripoli, Roman Empire, Israel, Muammar al-Gaddafi |

Tripoli's ghosts

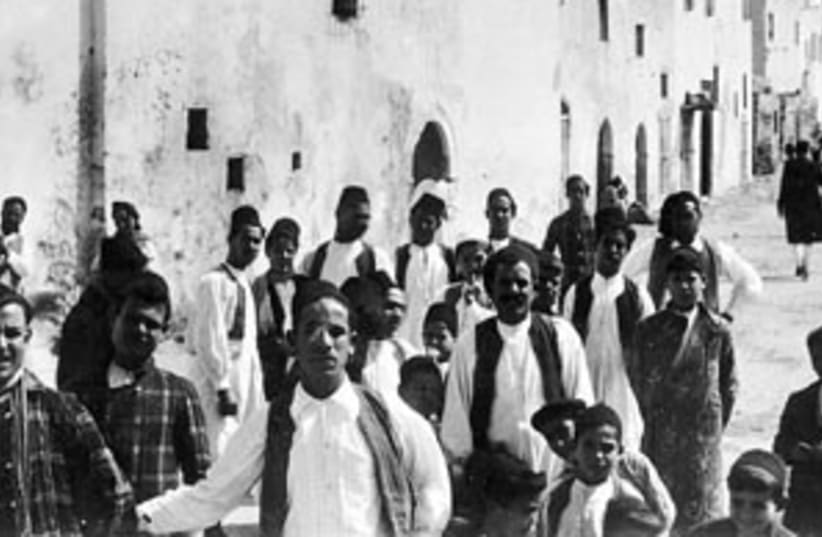

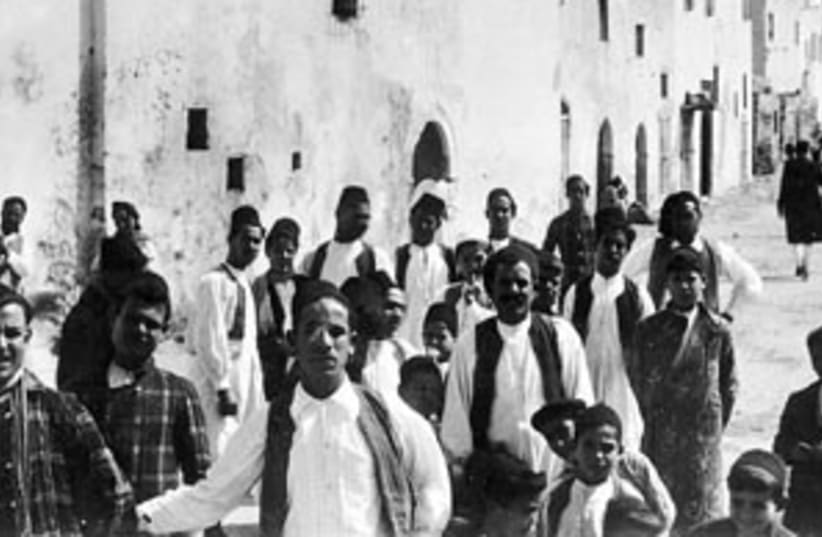

Libya was home to one of the most thriving Jewish communities, whose descendants want to visit the graves.

| More about: | Tripoli, Roman Empire, Israel, Muammar al-Gaddafi |