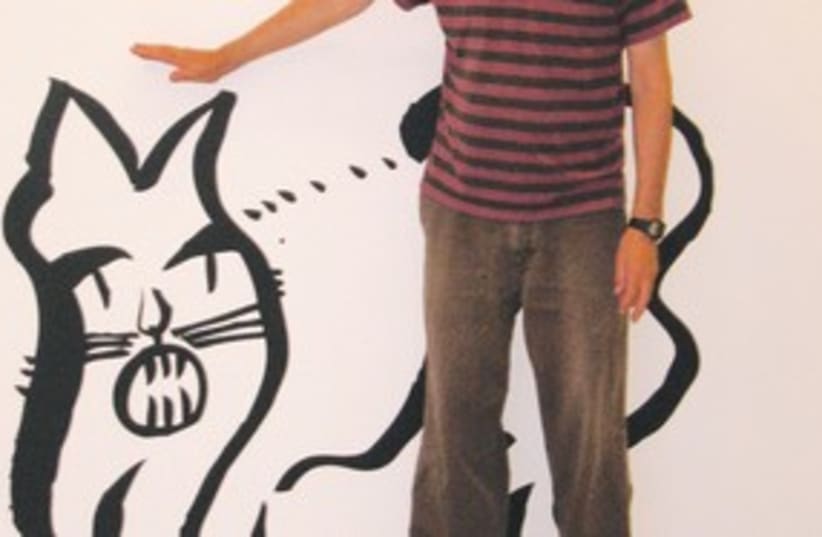

Drawings of cats seem to be a far cry from designing lights and chairs. Are you pushing the boundaries between art and design? Well, I started out years ago doing both industrial design and fine arts. I come from the two media. After doing art and industrial design, in the mid-1970s I moved totally to industrial design.Why?All my work in the mid-Seventies was narrowing according to the streams of that time – to minimalist art, which was dry. And I was drying myself up with this art and decided to start full-time with industrial art. And since then I’ve been doing industrial design in two areas, lighting and furniture. And I have doing research and studies in morphology, the form, shape and structure of things.I’ve published two books. One of them had to do with the study of a chair, which somebody once said is an animal with four legs. It was a morphological study, a history of the chair, all made in drawings.Did you benefit from any early influences? I didn’t want to be what my father was. My father was a shoemaker. He did the upper part of the shoe. He was a craftsman, working at home. I spent much of my childhood seeing how a product is made. He was a craftsman doing things, and I am a designer designing things. Very similar – and yet very different. My father would never dare to change a model, which for him was like something from God. And I wanted to be more like God, making and changing the model.So what is the difference between art and design? Art is looking at life from above. The aim of art is to look at life in many, many ways. It shouldn’t be about creating something functional. Design is about creating something functional. Like this cup, or a hook that you hang your hat on, or your glasses – it’s something that you use.There are, of course, certain things in art and design that are the same. The tools that we use – a designer is drawing his idea, a draftsman is drawing his idea, and an artist is also drawing his idea. So these tools of drawing form links among to many individual kinds of media. So I’m making drawings that are technical, and with the same stroke I’m sometimes running away to “unfunctional’ drawings.But my interest is really shape, structure, morphology. This is kind of universal. An architect can have the same interest, a painter can have the same interest, but the outcomes will be different.Is the creative process the same? Well, the creative process is always an enigma. I also teach, and I look at my students, and I’m always puzzled, again and again, about how people behave so differently. You can never make big, general assumptions about the creative process. That is a very personal, individual thing that cannot be generalized.Is your current exhibit of cat drawings “art”? No, I call them morphological studies. Ninety percent of these drawings were done in front of the TV, during commercials or boring parts of the program. It’s a kind of pastime. It started when a friend of mine, a veterinarian, had her 40th birthday. So I did 40 drawings. After you have a group of 40, something tickles you. So, I’ve continued.Why a cat?Just by accident. It could have been a dog, a horse, or anything else. We have a cat at home, and that became the model for what I was looking at.

So what were you looking at? I would say it’s about how to draw a cat – how a blank page, at a certain moment, becomes something you can point to and say: “This is a cat, this is its head, this is its face, this is its tail,” and so on. It’s when something becomes something. This is what interests me. And in many cases, the context is important also.If you took many of these pages out and looked at each one individually, you wouldn’t recognize them as cats. Because it is here, you can relate to each one as a cat, because of the context.What is the minimum number of marks you need to make on a page before someone can call it a cat? I don’t know. One or two of these were made with just one stroke of a brush. You look, and you decide whether you see a cat or not.There is an old saying to the effect that a camel is a horse designed by a committee. Having made over 4,000 morphological studies of the cat, would you say that it is designed well or badly? For me, the cat is designed perfectly. And as for the saying about the camel, it was probably invented by people who own horses, not by Arabs or Mongolians. Of course the Arabs and Mongolians might differ on how many humps a camel should have, one or two.Were any of your previous exhibitions similar to this one? I exhibit frequently, usually once or twice a year. But these exhibitions are usually of products. My last exhibition like this was about circles, rings, a morphological study of rings.When does a piece of metal become a ring? I had about 300 rings. And I’m now going to make a book out of it, the morphology of the ring. Rings are more abstract, not like cats, but like the cat exhibition, it’s all about when something starts to become something, or ceases to become something. When is the thing enough to be a ring, or too much to be a ring – like a popular dish cooked with so many spices it becomes inedible.There have probably never been so many drawings of a cat – or anything, for that matter – assembled together in one place before. How were you able to maintain your interest in this subject through so many drawings? You know the painter Mark Rothko? At certain times in the past when I saw his paintings, it always annoyed me how someone could spend his time painting one square into another and another, just changing some color, and so on. And when I was studying art, I promised myself that I would not repeat anything again and again.And now, I find myself obsessively doing the same thing, again and again. There are about 2,000 here, but when we were planning the exhibition, my curator Hanna Bergman took out about 50 percent of my drawings, so there are around 4,000 or more in all.But no two of these cats are the same.Yeah, the repetition is okay.Is it true that you do not use a computer, even when you’re doing complicated industrial design? Personally, I cannot use a computer. It’s simply after my time. If I’m doing three-dimensional things, like products, I design in my head and then write it down on the paper. When it’s things like this, the cats, then my mind is going down to the tip of the finger. I’m almost not there. I know that some designers don’t use their pens as a medium to transfer their ideas. They use other ways, like computers. Luckily I’m skillful enough to work with a page.You mention other designers. How would you characterize the state of design in Israel at the moment?Well, Israel is a developing country, but I think we are reaching a state of critical mass here, from hundreds of active young designers. We’re starting to see a lot of fresh, very good things. I think there are many very good signs. It’s also becoming more viable as a full-time profession. I make a living from it.

That, then, may be the biggest difference between design and art.

[Laughter.] I think that in general, in the art fields one is tempted to go into, people don’t look for money but for how to spend their lives. Artists are prepared to be hungry for some time; designers are prepared to be hungry for less time. Less time, and a lot less hungry. Still, I’d say that designers are prepared to be a little bit more hungry than, say, lawyers. So there’s a kind of sociological scale of who is prepared to be more hungry, and for how long. And who might please or disappoint his parents more.Are you done with cats? Have you gotten them out of your system? Yes.What’s next? Well, it’s a secret. Some people go to India for their inspiration, I go back to my sketchbook. I will say, though, that I have been drawing a lot of pictures of masks lately. African masks.Ya’acov Kaufman’s “Shunra” is showing until December 18 at the Israeli Museum of Caricature and Comics.

Tel: (03) 652-1849.