That's not the house Moshe Katsav grew up in. Born in Iran in 1945, Katsav and his family made aliya in 1951 and moved into the Kastina ma'abara, or immigrant transit camp, out of which Kiryat Malachi grew.

Located on the northern edge of the Israeli South, the town of Kiryat Malachi is named after Los Angeles, whose Jewish community was one of its prime benefactors. (Both places mean "city of angels.") Locals like to point this out to English-speaking visitors; however, the name association with Los Angeles has been about the only spot of glitter in this stagnant development town of 20,000.

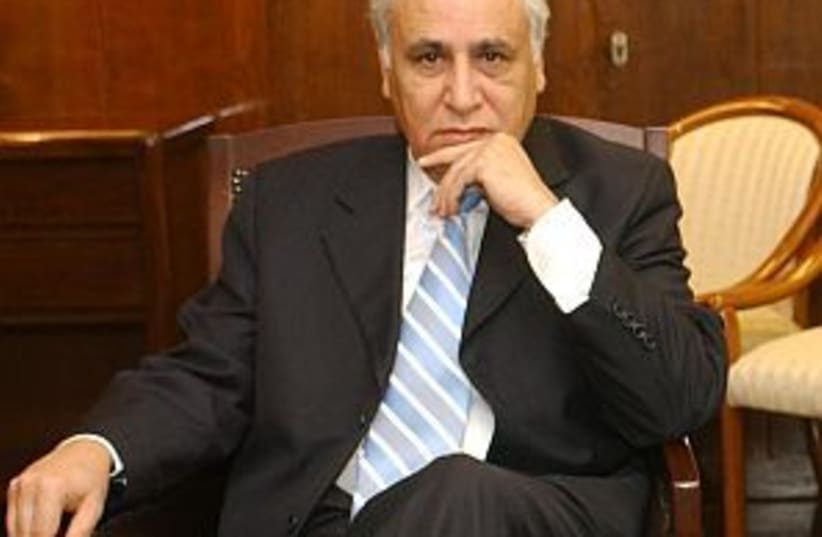

Until July 31, 2000, when, in a huge upset, the Knesset elected Katsav over the favored Shimon Peres as president of the State of Israel. Now, when the president went home on weekends, it wasn't to super-rich Caesarea, home of Katsav's predecessor Ezer Weizman, or to the aristocratic, Ashkenazi neighborhoods of Jerusalem, home to previous presidents, but to Kiryat Malachi, a backwater of what used to be called "the Second Israel," the Israel of the Mizrahi poor.

Katsav is Israel's first Mizrahi president, first Likud president, and certainly its first development town president. He was a symbol of the underdog who made it to the top, and his success reflected on Kiryat Malachi. For the first time, the town had something to show for itself, a point of pride, a calling card.

A lot of people in town identify with him, and echo his resentment against what they consider false charges, and blame his troubles on forces in Israel who couldn't tolerate such a low-born figure standing at the pinnacle of the nation.

"It's all out of envy," says Juliet Zano, sister of Ilana Attia, sitting in their yard next to the Katsav house. "He's the little boy who grew up to be bigger than any of them. People will do anything out of envy. I know 100 percent, 1,000 percent, that he's innocent. One day all the people who threw dirt on him will come and beg for his forgiveness."

In the Toto/Lotto candy store/cafe in what passes for downtown Kiryat Malachi, Meir Vaknin, a contractor sitting and smoking with several other middle-aged men, maintained, "It's a conspiracy against him by all those who didn't want him to be president in the first place."

Did he mean Peres, who now is gunning to become Katsav's successor? Or Binyamin Netanyahu, who has the Likud to himself now that Katsav won't be returning to politics as a beloved ex-president?

"I'm not accusing anyone," Vaknin said diplomatically. "But there's a lot of factionalism going on."

FROM BOYHOOD in Kiryat Malachi, Katsav was uncommonly ambitious. The eldest of eight children, he headed the local chapter of Young Bnei Brith, then went on to write for Yediot Aharonot and earn a degree in economics and history at Hebrew University in 1971.

Katsav was the first resident of Kiryat Malachi to attend the university in Jerusalem. Once there, he headed the campus Likud faction while teaching high-school math and history to support himself and his family.

While still studying, he was elected mayor of Kiryat Malachi in 1969 at age 24 as the coalition leader representing Gahal and the National Religious Party. Katsav, the youngest Israeli to serve as mayor, only stayed in that capacity for a mere two months before a second round of elections forced his party out of the coalition. He was reelected mayor in 1974 and then entered the Knesset with the Likud upheaval of 1977. While in the Knesset, he held a number of high-profile positions, among them: Labor and Welfare Minister, Transportation Minister, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Tourism.

Part of the first generation of development town Mizrahim to stake a claim in Israeli politics, Katsav naturally became a member of the camp of the pioneer of that movement, David Levyr. However, Katsav never fit or tried to fit the profile of an Israeli ethnic politician - he wasn't angry enough, in fact he wasn't angry at all, and was known for his friendliness and graciousness and his shining smile. He was a solid establishmentarian.

Yet it was his appeal to Mizrahi solidarity that won him the presidency in 2000; through the agency of fellow Mizrahi Likudnik Silvan Shalom, Katsav convinced Shas, which was in the Labor-led government, and probably also David and Maxim Levy, who were part of prime minister Ehud Barak's One Israel list, to cast their secret ballots for him.

In a recent interview, Katsav suggested that the antipathy for him in the media was based on ethnic prejudice. But this theme is not picked up by the people of Kiryat Malachi.

"No, they go after all the politicians. Look at Haim Ramon, he's Ashkenazi," noted Ilana Attia in her backyard.

"I'm not saying it's ethnic," said conspiracy theorist Meir Vakhnin at the Toto/Lotto shop, likewise bringing up the example of Ramon, who is standing trial for forcibly kissing a woman.

Kiryat Malachi is consistently at the top of the national unemployment and welfare-recipient lists. It is usually grouped with other southern development towns such as Kiryat Gat, Sderot, Ofakim, Dimona, Netivot and Yeroham, whose populations are likewise based on poor Mizrahi, former Soviet and Ethiopian immigrants. Yet Kiryat Malachi is hardly in the periphery at all. Sitting 17 km southeast of Ashkelon, you have to travel a long way south before the desert begins.

Nevertheless, it is a backwater, a place young people dream of escaping. A couple of blocks from Katsav's home, on Rehov Jabotinsky, stand old, ruined, trash-and-graffiti-marred tenement buildings that look as if they should be condemned. The slums here are real slums. On a "downtown" corner, we asked some kids trotting by where the local mall was, and they pointed in two different directions. A man overhearing us laughed softly and said, "There's no mall here like the kind you're looking for."

When we told them we just wanted to find people with time to talk, he pointed down the street to the shops and little cafes and falafel and pizza joints; this is the entertainment life in Kiryat Malachi.

TO OUTSIDERS, the most important thing about Kiryat Malachi is that it's the hometown of the president. To the people who live here, though, that interesting bit of trivia is badly overshadowed by the entrenched poverty and dreariness of the town. And Katsav's long career as mayor, MK, minister and finally president didn't change that at all.

"He didn't do a thing as mayor," says "Ruth," sitting in front of her Jabotinsky tenement with two friends. "We hoped that he would raise Kiryat Malachi up, but he didn't," says "Shoshana," her neighbor. Even after he became president, Katsav didn't use his power for the benefit of his home town.

"When his brother Lior was mayor, and the city workers hadn't been paid for a year, they went to his house to protest, and he went out the back door," said Avi, one of the men sitting around the TV in the National Lottery Toto/Lotto shop.

However, it's hard to say that Kiryat Malachi's enduring miseries have cost Katsav local sympathy for his legal battle. Meir Vakhnin, for instance, says, "Except for giving us a good name, Katsav didn't do anything for us. But that points to his honesty."

And tenement-dweller Ruth, who wrote off Katsav's five-year mayoral tenure as empty, contends nevertheless that he is the victim of "false charges made by that woman ["Aleph," the first of ten women to accuse him of sex crimes] because he refused to give her money."

This is a small town where if everybody doesn't really know everybody else, everybody thinks they do.

"I don't want to say anything bad about him, my mother is his neighbor, that's all I need - for them to read that I'm talking against the president," said Shoshana.

Rumors about Katsav are kept strictly off the record. So are flat-out declarations of belief in his guilt.

There are a lot of warm, loyal, neighborly, sentimental people in Kiryat Malachi, and Katsav gets a lot of moral support from them.

"I pray that God will save him," says Germaine Zano, 82, his neighbor for 30 years.

"My dream is to bring him a wreath of flowers on the day he is found innocent," says Zano's daughter Juliet.

But not everyone in town is so sentimental. "They say where there's smoke, there's fire," says Juliet's sister, Ilana Attia.

And some people in town aren't sentimental at all.

"I know Aleph," says a man on his way out of the Toto/Lotto shop, "and I challenge any man to stand face-to-face with her and not get a hard-on!"

While the people here might be expected to rally en masse around the pride of Kiryat Malachi, blaming the media and the "elites" for taking out a contract on him, there seems to be a considerable body of local opinion that treats the Katsav affair very matter-of-factly.

"There will be an indictment, and in the end he'll get off lightly," says Avi, citing the many other Israeli politicians whose trials have ended this way.

"I don't know if he did it or he didn't do it," says Ilana Attia. "I only hope the truth comes out."

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, when Mizrahim of the "Second Israel" were starting to speak up and emerge from anonymity thanks, in part, to the emergence of a cadre of Mizrahi development-town politicians, the stark decline of Moshe Katsav might have ignited a spirit of outraged solidarity among the people of Kiryat Malachi.

But that era has passed. Politics doesn't mean what it once meant, and politicians aren't anybody's heroes anymore. Today, Moshe Katsav's fate doesn't seem all that terribly important to most of his townspeople.

"We don't talk about it with the people we know," says Attia.

Even here, the Katsav affair isn't a matter of life and death, but rather, finally, a juicy news item, something you watch on TV.