Some 2,000 years ago, one scribe wrote at least eight of the Dead Sea Scroll manuscripts, making him the most prolific sofer ever identified, according to a group of scholars.

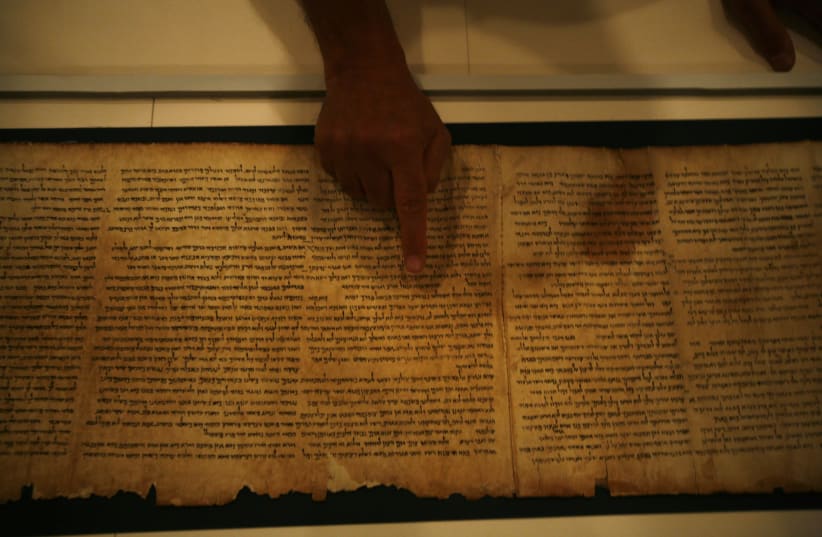

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a corpus of some 25,000 fragments unearthed in caves on the shores of the Dead Sea in the 1940s and ’50s. The artifacts include some of the most ancient manuscripts of the Bible, other religious texts that were not accepted in the canon and nonreligious writings.

Over the past few years, an artificial-intelligence-based paleographic project carried out by scholars at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and supported by the European Research Council has been focusing on understanding more about the identity of the scribes who copied the scrolls.

“We are pioneering Qumran research at the level of the individual scribe,” paleographer Gemma Hayes told The Jerusalem Post last month after presenting the preliminary results of her research at an academic conference at Groningen.

“The main purpose of my work has been using artificial intelligence, an extraction algorithm and statistical analyses to test 51 manuscripts that share a particular handwriting style,” she said.

The style is known as round semiformal.

“It’s a very beautiful handwriting that dates back to the late first century BCE,” Hayes said.

The manuscripts analyzed by the researchers had already been grouped together in the past. Celebrated paleographer Ada Yardeni, who passed away in 2018, suggested that some 90 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments featuring this specific style were the work of one individual.

“[Yardeni] had a method,” Hayes said. “She identified the specific way a certain letter, a lamed, was written, and she argued that based on this letter, you could group all these manuscripts together.”

The researchers have not been able to test all of the manuscripts Yardeni clustered together because some of them did not present enough material for the technology to examine them.

“We need a certain amount of characters,” Hayes said.

The results from the 51 artifacts that were tested were very significant: The system recognized that eight of the manuscripts were written by the same person, making him the most prolific scribe ever identified, in addition to demonstrating his ability to work in two languages.

“One of the really exciting aspects of our findings is that these manuscripts are very diverse,” Hayes said. “We found seven Hebrew manuscripts and one Aramaic manuscript, so-called sectarian manuscripts associated with the community in Qumran and nonsectarian manuscripts, as well as some para-biblical texts, including the one known as the testament of Naftali and some writings about Rachel and Joseph.”

Among the scrolls written by this individual author is the iconic Miqsat Ma’ase ha-Torah (MMT) scroll, considered by scholars a foundational document of the Jewish sect that many scholars believed lived in Qumran.

That the same person wrote texts of different natures might help shed new light on the identity of this community and their relationship with the rest of the Jewish people.

Scholars from “The Hands that Wrote the Bible,” led by Prof. Mladen Popovic, head of the Qumran Institute of the University of Groningen, used their algorithm to recognize background and foreground and to measure the movement of the writing and calligraphy.

The system allowed them to establish whether manuscripts that looked very similar were actually written by the same person or just in the same style.

“The fact that many wrote in a similar way can potentially tell us something about the training they received,” Hayes said.

Apart from the eight manuscripts written by the same scribe, the rest were penned by the different people, with one possible exception: two fragments that could have been written by just one person. They are also very diverse and include some biblical manuscripts.

Hayes is continuing her research and is studying the texts’ spelling characteristics.

“I’m looking into putting flesh and bones into this scribe,” she said.