| More about: | Italy, Academy Award, The Syrian Bride, Mohammad Bakri |

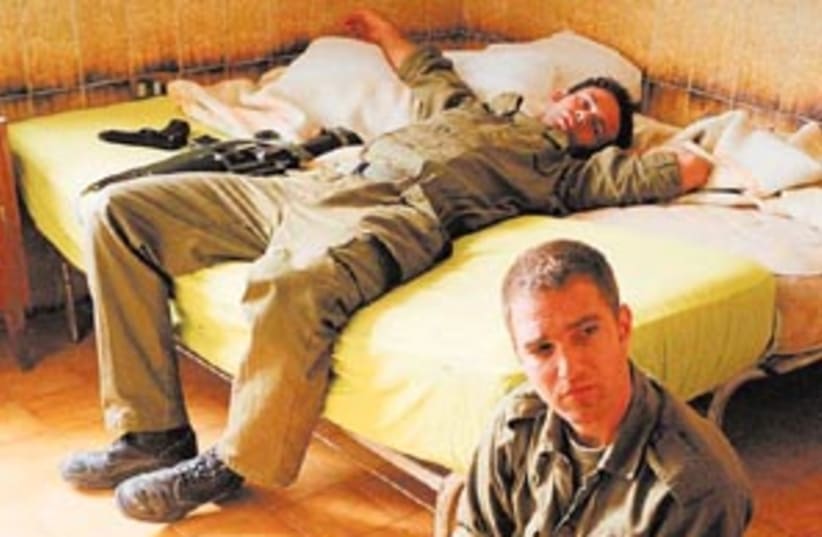

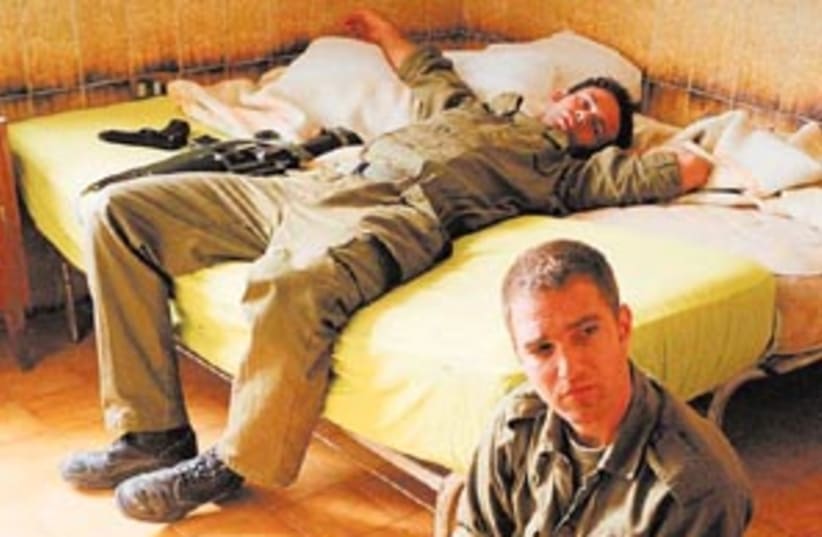

Oscars reject Italy's 'Private' submission

Producers hint disqualification due to pro-Palestinian slant, Academy says it's over language.

| More about: | Italy, Academy Award, The Syrian Bride, Mohammad Bakri |