Quentin Tarantino's latest movie may turn out to be many things, but one fate it will likely avoid is the controversial uproars raised by Munich and The Passion of the Christ.

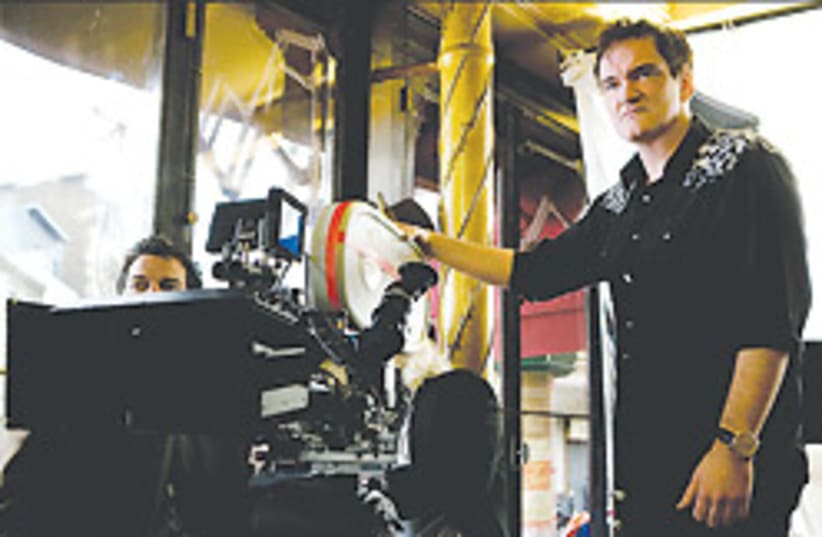

Weeks before it reaches theaters, publicity efforts are escalating into high gear for Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds, a very loose (and purposely misspelled) adaptation of a 1978 B-movie set in wartime Europe. The director will even come to Israel for the premiere in September.

Described as Tarantino's "new masterpiece" on the cover of next month's GQ, the film appears in many ways typical of its writer-director's previous work: filled with stylized dialogue, loaded with references to earlier films and, perhaps above all else, hyperviolent. But where Tarantino's earlier movies - Pulp Fiction, Reservoir Dogs, the Kill Bill films - dealt exclusively with fictional characters and were set mostly in Los Angeles, Inglourious Basterds takes the Oscar winner into new territory: the very real historical horrors of Nazi-occupied France.

"It is kind of surprising that he took this on," says Lawrence Baron, a University of California at San Diego history professor who has written extensively on film and the Holocaust. "It's not what you would expect from him."

Coming at the end of a decade that's seen fierce cinematic fights over depictions of Jews in works by major directors, Inglourious Basterds might appear in some eyes as perfect fodder for another round.

While it takes up one of the central conflicts of the Second World War - the Germans versus the Jews - Tarantino's new film adopts a highly unconventional - and highly fictionalized - perspective, focusing on a made-up unit of Jewish-American soldiers charged by their non-Jewish leader (Brad Pitt) with hunting down Hitler's occupying troops.

"Each and every man under my command owes me 100 Nazi scalps," the Pitt character orders, "and I want my scalps."

Despite the film's premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in May, many details of the plot remain unknown, as does the accuracy of Internet rumors that Tarantino has re-edited the movie. ("Those stories are all untrue," Harvey Weinstein, one of the film's executive producers, says in the new GQ.)

WHAT IS clear is the movie's irreverent view of World War II - for Tarantino, a period when Jews carved swastikas into German foreheads and a cartoonish Hitler attended a history-altering film premiere in Paris.

A trailer for the film released in February opens with a splattering of blood and the words, "Once upon a time."

Following an Oscar season that was especially laden with Holocaust-themed contenders, Inglourious Basterds has received a largely placid response in the run-up to its US premiere. In contrast to firestarters of the past five years - particularly Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ and Steven Spielberg's Munich - the reaction from the organized Jewish community has been silence, despite potential questions about the film's view of the German-Jewish relationship during World War II.

Several Jewish organizations declined to comment on the upcoming movie, with the Anti-Defamation League, a particularly vehement opponent of The Passion of the Christ, writing in an e-mail, "We have not yet screened the film. Until we do we defer comment."

Such a strategy stands in sharp contrast to the organization's response to the Gibson drama, an account of Jesus's final hours, described by the ADL as potentially "fuel[ing] latent anti-Semitism" with its portrayal of Jews as "blood-thirsty." The organization began voicing concerns about that movie months before its release, publicly requesting to see the script and a rough cut of the film. Asked in a follow-up e-mail whether its reticence about the new film might be related to the massive public interest generated by the controversy - The Passion grossed more than $370 million in the US - the ADL elected not to respond.

For another widely quoted critic of the Gibson movie, Simon Wiesenthal Center dean Rabbi Marvin Hier, the divergent reactions to the two films lie in their contrasting ambitions, with The Passion focusing on a story accepted as a "historical reality" by many viewers and Tarantino's movie avoiding similar claims. Emphasizing that he had not yet seen Inglourious Basterds, Hier rejected the suggestion that Jewish organizations might be holding back because of the experience with The Passion.

"I disagree with those who say it backfired," he said. "I think that when a [movie] has a possibility to spread hatred… it needs to be repudiated, and if such a film would be made again and would cause similar damage, I, for one, would speak out."

For Baron, who also hasn't seen Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino's latest project is hardly the first of its kind, falling into a genre of mostly European films that treat the Holocaust as a source of titillation.

"There is this whole tradition - it's not something new, but no one so high profile has made one," Baron said, citing a series of mostly Italian movies known as "nasties" or "video nasties" from the 1960s and 1970s that often exploited real events, including the Holocaust. "What I argue," he said, "is that the Holocaust has become a sort of major image of evil and has become a generalized image… It lends itself to many types of cinematic treatments, and from what I can tell this is first and foremost a cinematic treatment."

Hier, a two-time Oscar winner for his work as producer of The Long Way Home and Genocide, two documentaries dealing with the Holocaust, held out the possibility that the Tarantino film could do some good for the image of Jews in wartime Europe.

"If the Holocaust has shown one thing we have to fight against, it's the idea that we are sheep to the slaughter," he said. "Anyone has a right to create a script of fiction. If you take fiction out of Hollywood and filmmaking, there'd be hardly any movies left."

| More about: | Steven Spielberg, Quentin Tarantino, Mel Gibson, Brad Pitt |