Park or alight from bus #185 at Afek Junction, on Route #444. The jagged outline of the 16th-century Turkish- built fort at the source of the Yarkon River is the first port of call (there is an entrance fee). Prepare to spend at least an hour and half at the site; double that time to include the very pleasant gardens containing sources supplying water to the Yarkon.

The gently sloping view to the coast helps to explain its importance. It oversees the Via Maris, the ’Way of the Sea’ coastal overland trading route between the two major Middle Eastern powers of the day — ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia (now Iraq). Whoever commanded that site had a firm hand on the windpipe of international commerce and travel.

Joshua must have known the strategic value of Afek, as it was then known, and successfully targeted it (Joshua 12:18): a small portion of the Canaanite monumental building has been exposed just inside the gate of the fort, with arrowheads from the period found driven into the walls. The conquering Philistines, however, were a technologically advanced and far more formidable enemy. They occupied the coastline including Afek, and were making partially successful incursions onto the higher ground — to the continuing anxiety of Samson, Eli and Samuel. Their capture of Afek enabled them to rout the Israelites and carry off the Ark of the Tabernacle as a trophy from the battlefield (I Samuel 4).

LEAVE THE site the way you came in, and follow the Israel Trail signs across Route #483 for the first surprise of this 20 km., eight-hour trek: fields of ripening cotton in the shadow of Rosh Ha’ayin. Their flowers — cotton wool - contain tightly embedded cotton seeds extractable only with difficulty. I hadn’t realized that these natural fibers grow so far north. Neither had I expected to see rows of Beduin-type tents, which on closer inspection, I saw had the sole purpose of shielding the fields from the sun.

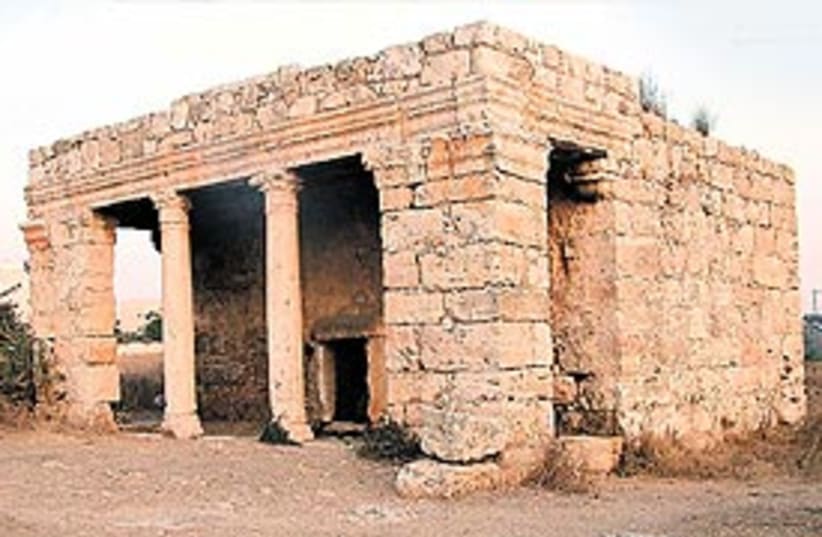

This small building with a classical portico comes as a surprise. Cube-shaped, the structure functioned as a family burial vault at the beginning of the fourth century CE. The very diminutive entrance is thought to resemble the open mouth of a dolphin, which was believed to accompany the deceased to the Next World. The adjoining room inside has some 60 incisions: it is unclear whether they were holes for raising pigeons as part of pagan Roman ritual, or whether they were to hold the ashes of the owner’s deceased slaves. It has survived in good condition, as it subsequently became a venerated Muslim holy place, Makam en-Nabi Yahya. Use a flashlight to find the mihrab (Mecca- facing prayer niche) in the southern wall of the main room.

Right behind ancient Mazor is contemporary Elad, whose many newlyweds form a large part of its 100% religious population, which include virtually all streams of Orthodox and haredi Jews. It offers affordable, well-designed housing, frequent bus services to Petah Tikva and Tel Aviv, and a sea view down to the Mediterranean. Its accelerating population growth approaching 30,000 souls and 18 synagogues contains (in contrast to nearby Modi’in) few native English speakers, other than a handful of Americans of Sephardi origin. This settlement is fenced off from Mazor, and also from the Israel Trail, which skirts its southern side.

Opposite are the remains of the far more basic settlement of Hatzrot Koah. The Hebrew letters kaf het spell ’strength.’ They also have the numerical value of 28 — in commemoration of that number of soldiers killed in the struggle for the nearby strategic high ground in the 1948 War of Independence. More recently, its caravans have served as emergency temporary housing for Ethiopian immigrants, as the supply of suitable accommodation at nearby Modi’in reached saturation-point.

Now comes the most pleasant part of the walk. Candle- shaped, well-placed cypress trees herald Israel Trail and other walkers into very attractive mixed Mediterranean woodland. Faint but unmistakable fragrance breaks through — of fresh eucalyptus, oaks, pines, cedars and cypress.

The amply shaded area climbs steadily above the Mazor Valley, for much part avoiding the scars of the nearby quarrying. Within an hour from Mazor, the trail clambers over limestone outcrops, and then plunges down into a 250- meter ruler-straight tunnel under Route #6. These tunnels do not only serve the walker, but link together wildlife communities arbitrarily fragmented by the recent construction of the Trans-Israel toll highway.

I trod carefully, half-expecting to disturb a community of snakes or hyenas, but the wildlife yearning to reunite with their brethren on the other side - if any — were appropriately discreet. The same could not be said of the horned cattle a little further on, but they soon relented and returned to their lazier pursuits.

With glimpses of the red roofs of nearby Shoham, and the chimneys of Reading Power Station at Tel Aviv far beyond, the rest of the way to Modi’in proved to be a losing battle against the gathering dusk — those wishing to examine the Roman-Byzantine mosaics, water cisterns and neatly cut stones of Navalat (entrance is free), just north of the modern settlement of Beit Nehemia, should time their arrival more wisely. Better hurry before it is fenced and zoned as a pay-as-you-enter tourist attraction.

The path becomes challenging towards the end with its steep ascent through olive plantations to the remains of the late-Bronze Age settlement of Tel Hadid — which received a mention in the writings of Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (fourth century CE) and on the Madaba Map (sixth century) in Jordan. By now, you may feel you are on an endurance test — proving your loyalty to the trail.

Eventually, the way descends under Route #443 to a clearing of oak trees, facing Mitzpe Modi’in — covered in the next stage of the trail. The bus stop is a short walk westwards, with services to Lod.

| More about: | Ottoman Empire, Yarkon River, Rosh HaAyin, Petah Tikva |