I have just finished reading a book. Well, that’s not unusual – I read at least one book a week. Sometimes I even review them. But this one was different from any book I’ve ever read.

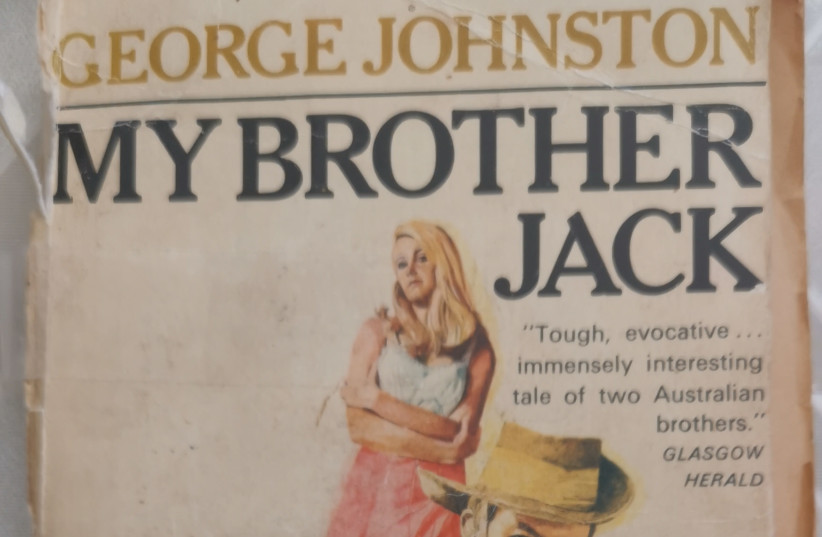

My sister Bobbie (Roberta) now 97, had been trying to get me to read it since 1964, when it was first published. I never would. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s because it’s a battered paperback with the cover half-torn off. Maybe because the print is small. I kept avoiding it. But just before the pandemic, miraculously, I went to visit her in my birthplace, Melbourne, Australia – and when I unpacked when I’d returned to Jerusalem, she’d somehow smuggled it into my luggage. A year has gone by, and just now I finally read it.

When I closed the last page, my eyes were wet. I wouldn’t call them tears – just all the memories leaking out. For this amazing book took me right back to my childhood – my parents, my siblings (three of whom are no longer alive); the shabby house at 9 Jackson Street, St. Kilda (which has been pulled down and a block of flats built there); the child I was – the way we spoke; the way we lived … The book is called My Brother Jack by George Johnston, a journalist whose byline I remember from the newspapers we read.

It’s a riveting story about a poor family after World War I – the father a drunken bully; the mother a nurse; the older brother Jack a tough guy – “a larrikin” – fighting, drinking, swearing and “wenching.” It’s narrated by his young brother Davy, just as World War II is about to begin. This was my childhood (not like his parents), but the way we used to speak, idioms you wouldn’t understand if you hadn’t lived there at that time. Jack always called his young brother “Nipper” which is what my brothers called me (they were 14 and 12 when I – the fifth child – was born.)

The suburb they lived in was like St. Kilda where we lived. They weren’t exactly slums – they accepted their mediocrity and strove for suburban respectability. Our street was behind Fitzroy Street and The Prince of Wales Hotel, so at weekends you had to avoid drunks lurking around. And once the war started and the Yanks came to Australia, the queues of soldiers and sailors filed into Molly Delafield’s house. She lived in our street – a “lady of the night” whom in my childish mind I thought of as the most popular woman in Melbourne as she had so many friends visiting her.

As I turned the pages, I was there. I was eight-years-old again. We were very poor although I don’t suppose I realized it because it was the Depression and no one had money. My pocket money was a penny a week, and if I saved up for four weeks, I could buy an ice cream. If I wanted to visit a friend, I could only do it if I had enough money for the tram fare. Or they lived close enough to walk there. Dad was an accountant, whose only relaxation was putting five shillings each way on his favorite in the horse races. If he lost, the atmosphere was bleak.

If he won, at good odds, he would say: “We’re all going to the pictures!” and mum would put on her “best” dress and we’d go to the Memorial Cinema (affectionately known as “the flea house”) for a magical evening… first “The March of Time” newsreel, followed by a Western with John Wayne, or a musical. And if he’d had a really good win, we went out for coffee afterward. One such night we saw my 3rd grade teacher there – Mr. Webb – and dad invited him to join us. I felt like the luckiest and happiest little girl in the world.

AS I WAS growing up, I wanted to be rich so that I could buy my mother pretty new dresses. Her ambition was to be “a lady in a flower shop” but my dad said self-righteously: “No wife of mine is going out to work” as she slaved from morning to night cleaning and making delicious meals from the cheapest ingredients for our family of seven, with no household appliances at all – not even a refrigerator, but an ice-chest.

A man with a horse and cart would come once a week to bring a block of ice for sixpence. His horse would leave manure on the road, which dad would collect and always say: “God’s gift to the garden.” My mother loved geraniums and grew them in all colors... red, pink, white, purple... because they grew from cuttings that other gardeners gave her.

I read the book and my heart broke with every page, because it was my family’s story and I was there again. Today I could help my parents have an easier life... even install mum as “a lady in a flower shop,” but it’s too late. There are just memories.

So I am looking back trying to remember the little things, because now I realize they were the big things. When we leave a place, we leave something of ourselves behind. And there are things in us that we can find again only by going back there.

Today my yesterdays are walking with me. They keep step and are the faces that peer over my shoulder. Even if you forget your past, it remembers you. And so I read the book my sister always wanted me to read. And somehow it has changed my life and I will never forget where I came from.

This battered paperback I avoided for so long has become a treasure!

The writer is the author of 14 books. Her latest novel is Searching for Sarah. dwaysman@gmail.com