Battle for the beach

A private contractor has begun building a resort on one of Israel's last remaining "wild" beaches.

(photo credit: Michael Green)

Battle for the beach

Crouching precariously on a small outcrop of rocks 20 meters from the shore, Sameer Mabjeesh grasps his rod, hoping to catch one of the fish swimming off the Israeli coast in the Mediterranean Sea. "I didn't catch so many today," he concedes. "But I don't really come here just for the fish, it's for contact with nature. I've been coming to this beach for over 20 years. I know this place, I love it."

As the waves lap at his feet, the orange glow of the setting sun signals that it is time for Mabjeesh and half a dozen other fishermen to pack up and go home for the day. Today's catch will be mostly for his mother, he says before setting off for the 15-minute drive back home to Rehovot, where he works at the Faculty of Agricultural Science on the Hebrew University's satellite campus.

The small, secluded bay where Mabjeesh comes to catch fish three or four times a week is surrounded by the Palmahim Beach National Park and lies immediately south of Kibbutz Palmahim, halfway between Tel Aviv and Ashdod. The beach itself may be small, but it is much loved by the fishermen and beachcombers who seek a refuge there from the urban sprawl of other parts of the country.

"It's special because there are no people. The beach is better [the way] it is now," says Oded, who is playing matkot (paddleball) with his girlfriend on the larger, commercial Palmahim Beach a few minutes' walk south. Indeed, the intimate spot, known to locals as the "fishing" or "wild" beach, seems forgotten by the rest of the country, all but deserted except for a handful of amateur fishermen and a small boat - until now.

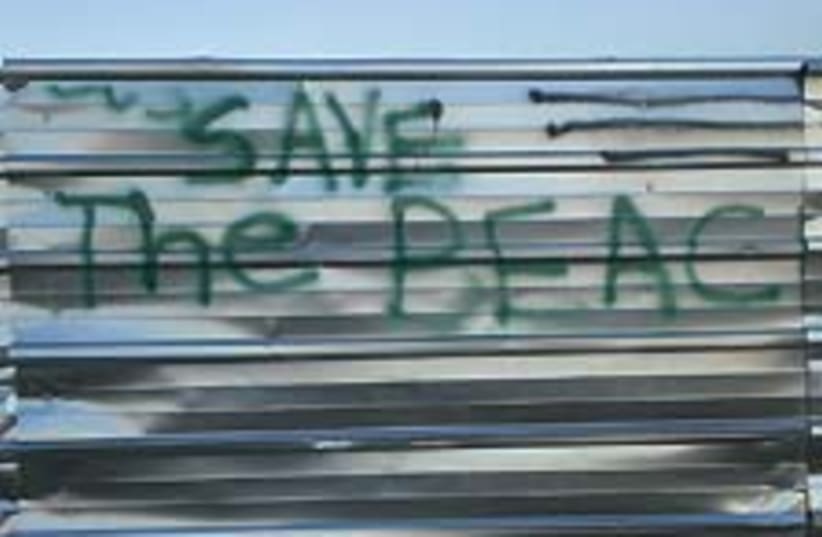

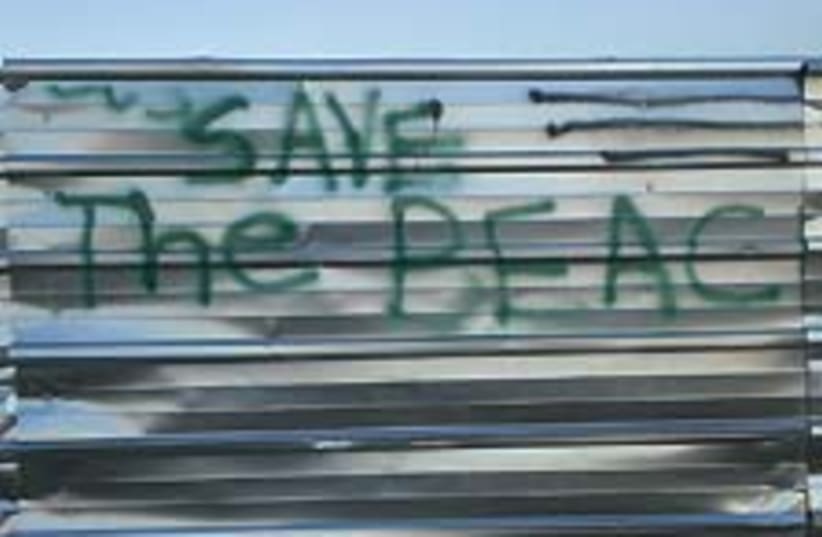

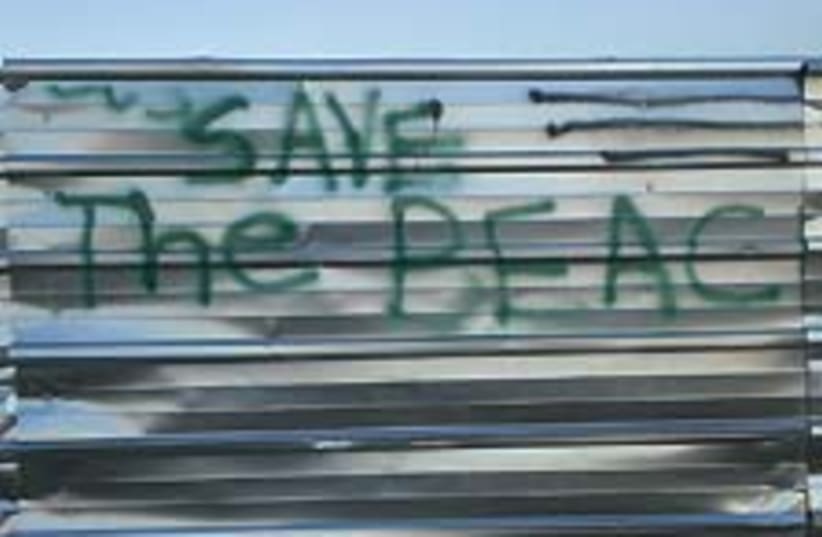

Construction has recently begun on a 350-room resort, Kfar Nofesh Palmahim. Fishermen, beach visitors, and locals fear the project will destroy what they say is one of the last open, "wild" spaces on the country's coast.

Plans for the resort include low-rise villas as well as a spa, health club, swimming pool, conference center and an 18-dunam public parking lot. Although the Gan Raveh Regional Council approved the Palmahim beach for tourism development several years ago, many were shocked when building commenced a few weeks ago.

"I live very close to Palmahim and try to go there every day to watch the sunset," explains Adi Lustig, 18, a high-school student from nearby Moshav Beit Oved. Lustig says she first saw the construction about three weeks ago. "It was so sudden… [Local] citizens didn't know anything about the construction work until they put the fences up."

In an attempt to rally people around her cause, Lustig organized a demonstration at the fishermen's beach last Sunday. Over 100 people participated. "It's our beach. We don't want the buildings there. I don't want them to ruin it - I want to stop them," says Lustig, who has been protesting the construction by sleeping in a tent on the beach for over a week. "They're going to ruin everything here. This place is the only [unspoiled] beach we have."

Kibbutz Palmahim residents were also taken by surprise. "The situation is very unclear. The building has been going on for just a few weeks. It started quietly, so many local people don't know about it," says R., who prefers to remain anonymous. "It's very strange. It took me a long time to realize what was happening."

While some parts of Palmahim Beach already feature showers, lounge chairs and cafés, the "fishermen's beach" has remained practically untouched. But access is already being limited and fishermen can hear the hum of vehicles razing the ground. A two-meter-high metal fence has recently been erected where the fishermen used to park. Now, many of them park at the main Palmahim Beach, which charges NIS 20 during the peak season, and carry their equipment to the bay on foot. "They're taking the seashore away from us, literally," says Mabjeesh.

Anyone enjoying a winter stroll along Palmahim's sun-drenched shore could be forgiven for forgetting that this is February, and two weeks ago parts of the country were covered in snow. According to locals, summer sees as many as 200 fishermen a day flocking to the tiny bay. Fishermen are worried about the effect that unprecedented volumes of tourists will have on their occupation. "It will be bad for the fish, because fish like the quiet. If there are cars, noise, lots of people and children, it will disturb them and frighten them away," says Zaven Vartanian, who has been fishing here for 30 years. "There are fewer fish [at the commercial beach] because there are people there all the time." The 55-year-old Ramle resident says he didn't catch much today, but it's not just the fish he comes for. "I come here three times a week. It's quiet here, and you don't have the chaos of the city - there's just you, God and water."

The rugged look and leathery skin of Shlomi Menahem, from Ness Ziona, bear testimony to the hours he has spent out on the rocks, in the salty spray. "I come here for fun, to spend time here and be with nature. It's quiet today, because people are at work during the week, but on Shabbat, it's full of people. It's amazing."

The Environmental Protection Ministry deems guarding the Mediterranean coastline from the demands of tourism and urbanization a national priority. The ministry's Web site states that: "The coastal strip serves a vital role as open space. Yet much of Israel's 190-kilometer shoreline is closed to the public, [taken up by] national infrastructure, defense, and building… While in 1948… each citizen had an average of 31 centimeters of coast at his disposal, this amount has shrunk to 2.5 cm of coast per person."

While none of the locals doubt that the resort will permanently alter the area's atmosphere and ecological balance, the property developer, Evelon, maintains that the villas will harm neither the environment nor the fishermen. "There won't be any pollution. According to our contract, we have to be connected to the sewage system, so waste won't be going into the sea," claims Offir Asher, one of Evelon's project partners. "The beach will always stay open. By law, it's a public area. The fishermen are still going to have access, one way or another… We definitely won't stop people from coming to the beach - we want them there. People will be coming to stay [here] from all over the world, and we… want them to interact with Israelis."

But for many users of Palmahim Beach, Evelon's assurances fall on deaf ears. R. is "very concerned [about] the project. It's very close to the kibbutz and eating away at [our] free space for [the benefit of] people from the cities. It's the only public open space in this area; the land north of the kibbutz is reserved for military use."

Mabjeesh is equally skeptical: "In the summer, people come with their families and camp. It's a very nice atmosphere. I think it will be destroyed, they'll put up fences and private guards. It'll be just like the Kinneret."

"They want to destroy it all - the beach, the fish, the coyotes, all this nature. When I used to come here 20 years ago, I would see all kinds of wildlife - foxes, gazelles, and even crabs on the beach at night. But most of this has already been destroyed and what's left it is going to be destroyed too," believes Mabjeesh.

And not only the pastoral fishing beach will be affected by the new development, locals predict. They say that the larger, already developed stretch of Palmahim Beach will not remain unaffected by the influx of hundreds of tourists. "We're worried about the whole [of Palmahim] Beach," Lustig says.

A number of people have also questioned the development's legality. The border of the complex is slated to extend as close as 25 meters to the shoreline, although the buildings themselves will remain a distance of 100 meters from the water, according to Evelon's Web site.

"Something stinks. It feels dirty," Lustig maintains.

However, the Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority says the resort is as "legitimate as they come" and that the site does not lie within the Palmahim Beach National Park. INNPPA spokesman Omri Gal says that while the Parks Authority would "love" to turn Palmahim Beach into a nature reserve, the complex was authorized before the Law for the Protection of the Coastal Environment was passed in 2004 and before the interministerial Committee for the Protection of the Coastal Environment was established.

"The committee is usually very aggressive, and doesn't allow any building on beaches, but they don't have any power on this issue," says Gal. "The plan was authorized years ago by every committee it had to go through… Our job now is to minimize any [environmental] impact, especially on the adjacent National Park. The contractors have actually been quite cooperative with our demands."

Kibbutz Palmahim, founded in 1949 and now home to some 500 people, stands near the remains of an ancient city. The kibbutz's Beit Miriam Museum contains many archaeological artifacts from various historical periods. Museum director Dror Porat explains that the site slated for development contains a Hellenistic-period winery. "[Evelon] understands the importance of the site and wants to include archaeology in the [resort's] activities."

Evelon says it is "working as a team" with both the kibbutz and the government. "We are working closely with the Kibbutz Palmahim Museum. We'll allow them to bring people here, and our tourists will visit their museum, too," says Asher. "The Culture Ministry and the Israel Antiquities Authorities are completely behind the plan. We are in the process of debating whether to leave the winery in the Village, or move it."

The fishermen are skeptical: "Why is there going to be an archaeological site in a hotel? Will we even be able to go there?" Mabjeesh wonders. Further along the beach, Vartanian points to the notices designating the surrounding area a National Park: "Why build on history?" he asks.

Porat says the resort could benefit the local economy. "People here are not unemployed, but it will open good opportunities for kibbutz members… It will put us on the map… We want people to know about the area. It's an interesting place with a rich past." Porat says that the archaeological site isn't well-enough known. Calling himself "optimistic," he says he hopes for good relations with the resort. "The only thing I'm concerned about is the environment. I hope they'll preserve the coastline," he adds.

Campaigners against the resort believe that Palmahim Beach's intrinsic ecological and public value far outweigh any potential gain from development. "The beach is one place where we don't need [shopping malls and restaurants.] Work and money have to stop controlling our lives," complains Lustig.

Mabjeesh predicts that where one development springs up, others will follow. "I think it will be very commercial… It will be like the beach at Rishon Lezion. I don't know if tourists will be happy that [the resort] was built on [unspoiled] nature," he says.

Ultimately, however, the question at the heart of the battle for the beach isn't about jobs, fish swimming in the sea, or archaeological discoveries; it is whether a resort is necessary in the first place. "For sure, the resort is going to be beautiful for the tourists, the archaeology will be nice for them, but it doesn't serve the public interest. What makes the beach beautiful is that it's far from the city… That's what makes it different from Tel Aviv, Holon or Ashdod," Mabjeesh stresses.

Last Sunday afternoon, as the crowd of protesters began to disperse, Lustig returned to her beachside tent, which she says will be her makeshift home for "as long as it takes."

The Parks Authority believes that chances of stopping the development are slim. Gal says that people should have objected to the development plans when they were first presented, years ago. He says that at the time, the military could have weighed in and suggested that the resort not be authorized. "I think maybe some people didn't [protest] because they didn't think it would actually happen," Gal explains.

Evelon says that construction will start in earnest in April. "[The resort] is scheduled to open in September 2009, and has already been delayed. We signed an agreement with the government and must open according to the contract," Asher says.

Despite the prevailing feeling that the fate of Palmahim Beach is sealed, activists believe their battle is not in vain. "I really think it's possible to protect the beach," declares Lustig. "We can't give up, we have to stop it."

if(catID != 151){

var cont = `Take Israel home with the new

Jerusalem Post Store

(photo credit: Michael Green)

Battle for the beach

Crouching precariously on a small outcrop of rocks 20 meters from the shore, Sameer Mabjeesh grasps his rod, hoping to catch one of the fish swimming off the Israeli coast in the Mediterranean Sea. "I didn't catch so many today," he concedes. "But I don't really come here just for the fish, it's for contact with nature. I've been coming to this beach for over 20 years. I know this place, I love it."

As the waves lap at his feet, the orange glow of the setting sun signals that it is time for Mabjeesh and half a dozen other fishermen to pack up and go home for the day. Today's catch will be mostly for his mother, he says before setting off for the 15-minute drive back home to Rehovot, where he works at the Faculty of Agricultural Science on the Hebrew University's satellite campus.

The small, secluded bay where Mabjeesh comes to catch fish three or four times a week is surrounded by the Palmahim Beach National Park and lies immediately south of Kibbutz Palmahim, halfway between Tel Aviv and Ashdod. The beach itself may be small, but it is much loved by the fishermen and beachcombers who seek a refuge there from the urban sprawl of other parts of the country.

"It's special because there are no people. The beach is better [the way] it is now," says Oded, who is playing matkot (paddleball) with his girlfriend on the larger, commercial Palmahim Beach a few minutes' walk south. Indeed, the intimate spot, known to locals as the "fishing" or "wild" beach, seems forgotten by the rest of the country, all but deserted except for a handful of amateur fishermen and a small boat - until now.

Construction has recently begun on a 350-room resort, Kfar Nofesh Palmahim. Fishermen, beach visitors, and locals fear the project will destroy what they say is one of the last open, "wild" spaces on the country's coast.

Plans for the resort include low-rise villas as well as a spa, health club, swimming pool, conference center and an 18-dunam public parking lot. Although the Gan Raveh Regional Council approved the Palmahim beach for tourism development several years ago, many were shocked when building commenced a few weeks ago.

"I live very close to Palmahim and try to go there every day to watch the sunset," explains Adi Lustig, 18, a high-school student from nearby Moshav Beit Oved. Lustig says she first saw the construction about three weeks ago. "It was so sudden… [Local] citizens didn't know anything about the construction work until they put the fences up."

In an attempt to rally people around her cause, Lustig organized a demonstration at the fishermen's beach last Sunday. Over 100 people participated. "It's our beach. We don't want the buildings there. I don't want them to ruin it - I want to stop them," says Lustig, who has been protesting the construction by sleeping in a tent on the beach for over a week. "They're going to ruin everything here. This place is the only [unspoiled] beach we have."

Kibbutz Palmahim residents were also taken by surprise. "The situation is very unclear. The building has been going on for just a few weeks. It started quietly, so many local people don't know about it," says R., who prefers to remain anonymous. "It's very strange. It took me a long time to realize what was happening."

While some parts of Palmahim Beach already feature showers, lounge chairs and cafés, the "fishermen's beach" has remained practically untouched. But access is already being limited and fishermen can hear the hum of vehicles razing the ground. A two-meter-high metal fence has recently been erected where the fishermen used to park. Now, many of them park at the main Palmahim Beach, which charges NIS 20 during the peak season, and carry their equipment to the bay on foot. "They're taking the seashore away from us, literally," says Mabjeesh.

Anyone enjoying a winter stroll along Palmahim's sun-drenched shore could be forgiven for forgetting that this is February, and two weeks ago parts of the country were covered in snow. According to locals, summer sees as many as 200 fishermen a day flocking to the tiny bay. Fishermen are worried about the effect that unprecedented volumes of tourists will have on their occupation. "It will be bad for the fish, because fish like the quiet. If there are cars, noise, lots of people and children, it will disturb them and frighten them away," says Zaven Vartanian, who has been fishing here for 30 years. "There are fewer fish [at the commercial beach] because there are people there all the time." The 55-year-old Ramle resident says he didn't catch much today, but it's not just the fish he comes for. "I come here three times a week. It's quiet here, and you don't have the chaos of the city - there's just you, God and water."

The rugged look and leathery skin of Shlomi Menahem, from Ness Ziona, bear testimony to the hours he has spent out on the rocks, in the salty spray. "I come here for fun, to spend time here and be with nature. It's quiet today, because people are at work during the week, but on Shabbat, it's full of people. It's amazing."

The Environmental Protection Ministry deems guarding the Mediterranean coastline from the demands of tourism and urbanization a national priority. The ministry's Web site states that: "The coastal strip serves a vital role as open space. Yet much of Israel's 190-kilometer shoreline is closed to the public, [taken up by] national infrastructure, defense, and building… While in 1948… each citizen had an average of 31 centimeters of coast at his disposal, this amount has shrunk to 2.5 cm of coast per person."

While none of the locals doubt that the resort will permanently alter the area's atmosphere and ecological balance, the property developer, Evelon, maintains that the villas will harm neither the environment nor the fishermen. "There won't be any pollution. According to our contract, we have to be connected to the sewage system, so waste won't be going into the sea," claims Offir Asher, one of Evelon's project partners. "The beach will always stay open. By law, it's a public area. The fishermen are still going to have access, one way or another… We definitely won't stop people from coming to the beach - we want them there. People will be coming to stay [here] from all over the world, and we… want them to interact with Israelis."

But for many users of Palmahim Beach, Evelon's assurances fall on deaf ears. R. is "very concerned [about] the project. It's very close to the kibbutz and eating away at [our] free space for [the benefit of] people from the cities. It's the only public open space in this area; the land north of the kibbutz is reserved for military use."

Mabjeesh is equally skeptical: "In the summer, people come with their families and camp. It's a very nice atmosphere. I think it will be destroyed, they'll put up fences and private guards. It'll be just like the Kinneret."

"They want to destroy it all - the beach, the fish, the coyotes, all this nature. When I used to come here 20 years ago, I would see all kinds of wildlife - foxes, gazelles, and even crabs on the beach at night. But most of this has already been destroyed and what's left it is going to be destroyed too," believes Mabjeesh.

And not only the pastoral fishing beach will be affected by the new development, locals predict. They say that the larger, already developed stretch of Palmahim Beach will not remain unaffected by the influx of hundreds of tourists. "We're worried about the whole [of Palmahim] Beach," Lustig says.

A number of people have also questioned the development's legality. The border of the complex is slated to extend as close as 25 meters to the shoreline, although the buildings themselves will remain a distance of 100 meters from the water, according to Evelon's Web site.

"Something stinks. It feels dirty," Lustig maintains.

However, the Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority says the resort is as "legitimate as they come" and that the site does not lie within the Palmahim Beach National Park. INNPPA spokesman Omri Gal says that while the Parks Authority would "love" to turn Palmahim Beach into a nature reserve, the complex was authorized before the Law for the Protection of the Coastal Environment was passed in 2004 and before the interministerial Committee for the Protection of the Coastal Environment was established.

"The committee is usually very aggressive, and doesn't allow any building on beaches, but they don't have any power on this issue," says Gal. "The plan was authorized years ago by every committee it had to go through… Our job now is to minimize any [environmental] impact, especially on the adjacent National Park. The contractors have actually been quite cooperative with our demands."

Kibbutz Palmahim, founded in 1949 and now home to some 500 people, stands near the remains of an ancient city. The kibbutz's Beit Miriam Museum contains many archaeological artifacts from various historical periods. Museum director Dror Porat explains that the site slated for development contains a Hellenistic-period winery. "[Evelon] understands the importance of the site and wants to include archaeology in the [resort's] activities."

Evelon says it is "working as a team" with both the kibbutz and the government. "We are working closely with the Kibbutz Palmahim Museum. We'll allow them to bring people here, and our tourists will visit their museum, too," says Asher. "The Culture Ministry and the Israel Antiquities Authorities are completely behind the plan. We are in the process of debating whether to leave the winery in the Village, or move it."

The fishermen are skeptical: "Why is there going to be an archaeological site in a hotel? Will we even be able to go there?" Mabjeesh wonders. Further along the beach, Vartanian points to the notices designating the surrounding area a National Park: "Why build on history?" he asks.

Porat says the resort could benefit the local economy. "People here are not unemployed, but it will open good opportunities for kibbutz members… It will put us on the map… We want people to know about the area. It's an interesting place with a rich past." Porat says that the archaeological site isn't well-enough known. Calling himself "optimistic," he says he hopes for good relations with the resort. "The only thing I'm concerned about is the environment. I hope they'll preserve the coastline," he adds.

Campaigners against the resort believe that Palmahim Beach's intrinsic ecological and public value far outweigh any potential gain from development. "The beach is one place where we don't need [shopping malls and restaurants.] Work and money have to stop controlling our lives," complains Lustig.

Mabjeesh predicts that where one development springs up, others will follow. "I think it will be very commercial… It will be like the beach at Rishon Lezion. I don't know if tourists will be happy that [the resort] was built on [unspoiled] nature," he says.

Ultimately, however, the question at the heart of the battle for the beach isn't about jobs, fish swimming in the sea, or archaeological discoveries; it is whether a resort is necessary in the first place. "For sure, the resort is going to be beautiful for the tourists, the archaeology will be nice for them, but it doesn't serve the public interest. What makes the beach beautiful is that it's far from the city… That's what makes it different from Tel Aviv, Holon or Ashdod," Mabjeesh stresses.

Last Sunday afternoon, as the crowd of protesters began to disperse, Lustig returned to her beachside tent, which she says will be her makeshift home for "as long as it takes."

The Parks Authority believes that chances of stopping the development are slim. Gal says that people should have objected to the development plans when they were first presented, years ago. He says that at the time, the military could have weighed in and suggested that the resort not be authorized. "I think maybe some people didn't [protest] because they didn't think it would actually happen," Gal explains.

Evelon says that construction will start in earnest in April. "[The resort] is scheduled to open in September 2009, and has already been delayed. We signed an agreement with the government and must open according to the contract," Asher says.

Despite the prevailing feeling that the fate of Palmahim Beach is sealed, activists believe their battle is not in vain. "I really think it's possible to protect the beach," declares Lustig. "We can't give up, we have to stop it."

if(catID != 151){

var cont = `Take Israel home with the new

Jerusalem Post Store

Shop now >>

`;

document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont;

var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link");

if(divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined')

{

divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e";

divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center";

divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "40px";

divWithLink.style.marginTop = "40px";

divWithLink.style.width = "728px";

divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#3c4860";

divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff";

}

}

(function (v, i){

});