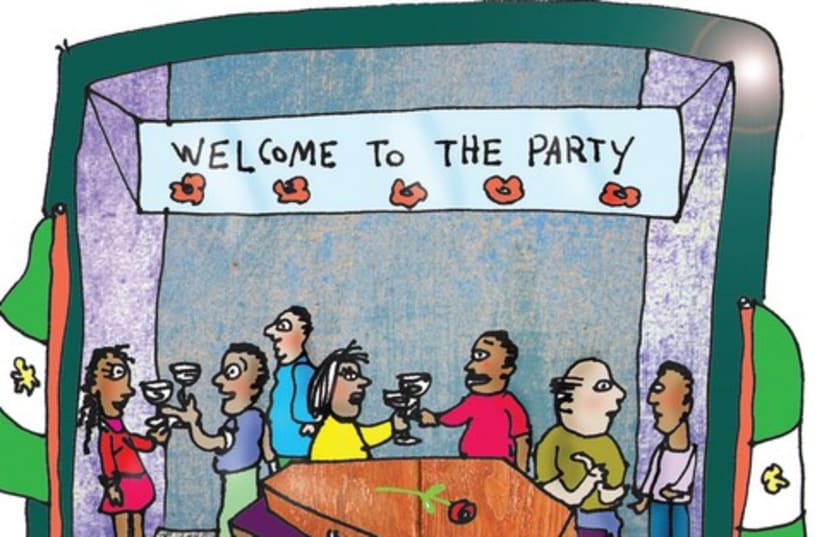

A friend’s mother passed away not very long ago. Before this, I’d remained largely unschooled in the customs that accompanied the loss of a loved one in these parts. So in a sense, I think of the week that followed as something of an education.Jewish custom demands that the burial take place as quickly as possible; this, of necessity, suspends the natural inclination to grieve until the necessary arrangements are made. My friend and one of her brothers live in the United States; a second brother was abroad for work. All three dropped everything to return for the burial as quickly as possible, while trying to coordinate the procedures that needed to be put in place. There isn’t time to grieve; there’s scarcely time to catch one’s breath. By the time one has the opportunity to step back and take stock, the burial is already over.There’s something very comforting about the custom of sitting shiva, I think. Emotions are processed together by those for whom the departed meant the most.Visitors stream in and out, sharing warm memories and fond recollections. Sitting shiva helps mediate the process of grieving. It doesn’t make that process easier – nothing can do that – but it makes it more bearable, more meaningful.My friend’s mother had been unwell for many years.Her passing was not quite a shock, but still, nothing can prepare one for the moment when it does occur. Bedridden, in time she came to require the constant assistance of an adult carer. I’m guessing that in her last few years, her carer became a close companion, given their close proximity from one day to the next. The carer was doing her job, of course. But it would be silly not to acknowledge that the two must have formed an emotional connection. The carer, a part of the family, was bereaved as well. You need not take my word for this; the biological family thought of her in these terms, too.Which created something of a problem. Like many in her position, the carer’s status in the country was determined by her employment, and her employment alone. Thus, from the moment of her erstwhile employer’s passing, she had 30 days to pack up and leave.She doesn’t want to go. She makes her living in this country, and she’s made a life in this country. It isn’t a great living; the hours are long, and the work is challenging.But it suits her needs. There are complicated arguments about the morality – or otherwise – of “importing” foreign workers to do the jobs that Israelis won’t do because the pay is so poor, but I’ll gloss over these. Whether fair or not, it is correct to say that the carer made a choice (of sorts) to work in the country.And it is also correct to say that thanks to bureaucracy, she is about to leave the country, and not by choice.Bureaucracy, by its very nature, is faceless, impassive, monolithic. For this reason, one should hardly be surprised that the laws in Israel remain as they are despite attempts to replace them with something more sensitive and human. Still, there’s something cruel about the way it rips apart the life of a person in mourning. Not just cruel for the parties concerned, but cruel for the country as well.Think about it this way. There are many elderly, unwell people here in circumstances similar to those of my friend’s mother. The economics of geriatric care mean that there is any number of carers in a similar position. The situation is unhealthy, and it is a shame that there seems to be a lack of willpower to do something about it. You can think about it from the perspective of the family of the departed, too. No doubt, they appreciate the emotional, physical and practical support their loved ones received in their last days, the knowledge that the carers tried to make the twilight a slightly more bearable time.When I went to pay my condolences to my friend’s family, their hearts were only partly in the process of sitting shiva as they would have wished. They were taking turns making telephone calls, searching for information, advice, anything that might be of help to their mother’s caregiver. It’s dreadful, having misery heaped upon their bereavement. But that’s the way it is.It’s an exaggeration, I suppose, to suggest that the bureaucracy of the Jewish state is taking the meaning out of a proud Jewish tradition. But not a huge exaggeration, I think.

Shabbat Goy: Good Grief

One shouldn't be surprised that bureaucratic laws in Israel are faceless, impassive, monolithic despite attempts to replace them.

A friend’s mother passed away not very long ago. Before this, I’d remained largely unschooled in the customs that accompanied the loss of a loved one in these parts. So in a sense, I think of the week that followed as something of an education.Jewish custom demands that the burial take place as quickly as possible; this, of necessity, suspends the natural inclination to grieve until the necessary arrangements are made. My friend and one of her brothers live in the United States; a second brother was abroad for work. All three dropped everything to return for the burial as quickly as possible, while trying to coordinate the procedures that needed to be put in place. There isn’t time to grieve; there’s scarcely time to catch one’s breath. By the time one has the opportunity to step back and take stock, the burial is already over.There’s something very comforting about the custom of sitting shiva, I think. Emotions are processed together by those for whom the departed meant the most.Visitors stream in and out, sharing warm memories and fond recollections. Sitting shiva helps mediate the process of grieving. It doesn’t make that process easier – nothing can do that – but it makes it more bearable, more meaningful.My friend’s mother had been unwell for many years.Her passing was not quite a shock, but still, nothing can prepare one for the moment when it does occur. Bedridden, in time she came to require the constant assistance of an adult carer. I’m guessing that in her last few years, her carer became a close companion, given their close proximity from one day to the next. The carer was doing her job, of course. But it would be silly not to acknowledge that the two must have formed an emotional connection. The carer, a part of the family, was bereaved as well. You need not take my word for this; the biological family thought of her in these terms, too.Which created something of a problem. Like many in her position, the carer’s status in the country was determined by her employment, and her employment alone. Thus, from the moment of her erstwhile employer’s passing, she had 30 days to pack up and leave.She doesn’t want to go. She makes her living in this country, and she’s made a life in this country. It isn’t a great living; the hours are long, and the work is challenging.But it suits her needs. There are complicated arguments about the morality – or otherwise – of “importing” foreign workers to do the jobs that Israelis won’t do because the pay is so poor, but I’ll gloss over these. Whether fair or not, it is correct to say that the carer made a choice (of sorts) to work in the country.And it is also correct to say that thanks to bureaucracy, she is about to leave the country, and not by choice.Bureaucracy, by its very nature, is faceless, impassive, monolithic. For this reason, one should hardly be surprised that the laws in Israel remain as they are despite attempts to replace them with something more sensitive and human. Still, there’s something cruel about the way it rips apart the life of a person in mourning. Not just cruel for the parties concerned, but cruel for the country as well.Think about it this way. There are many elderly, unwell people here in circumstances similar to those of my friend’s mother. The economics of geriatric care mean that there is any number of carers in a similar position. The situation is unhealthy, and it is a shame that there seems to be a lack of willpower to do something about it. You can think about it from the perspective of the family of the departed, too. No doubt, they appreciate the emotional, physical and practical support their loved ones received in their last days, the knowledge that the carers tried to make the twilight a slightly more bearable time.When I went to pay my condolences to my friend’s family, their hearts were only partly in the process of sitting shiva as they would have wished. They were taking turns making telephone calls, searching for information, advice, anything that might be of help to their mother’s caregiver. It’s dreadful, having misery heaped upon their bereavement. But that’s the way it is.It’s an exaggeration, I suppose, to suggest that the bureaucracy of the Jewish state is taking the meaning out of a proud Jewish tradition. But not a huge exaggeration, I think.