Report: Fearing riots, prisons locked down amid deterioration of Palestinian hunger-striker

Muhammed Allan, who has been on hunger strike for 59 days, has been put on a respirator according to hospital spokesperson.

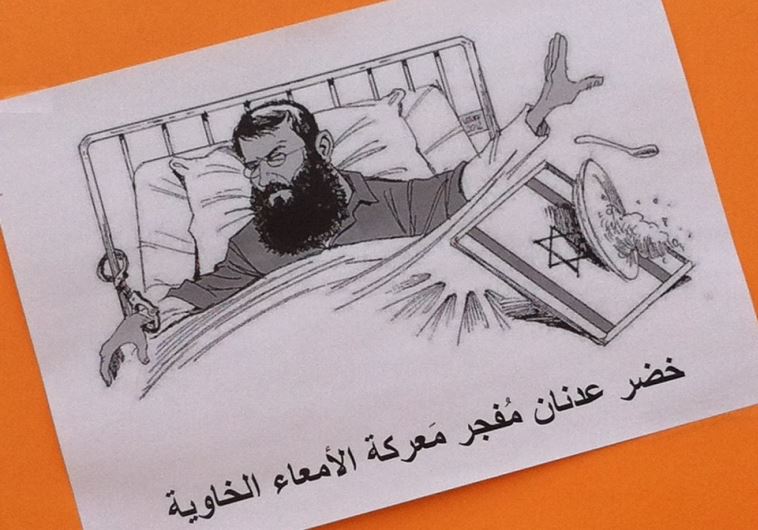

A handout supporting a Palestinian hunger striker.ByJPOST.COM STAFF, YASSER OKBI/ MAARIV HASHAVUAUpdated:

A handout supporting a Palestinian hunger striker.ByJPOST.COM STAFF, YASSER OKBI/ MAARIV HASHAVUAUpdated: