Rising nationalism vs globalization and how it affects the Jews

The Jewish Policy Planning Institute will convene its annual conference next week to deliberate key issues and make policy recommendations.

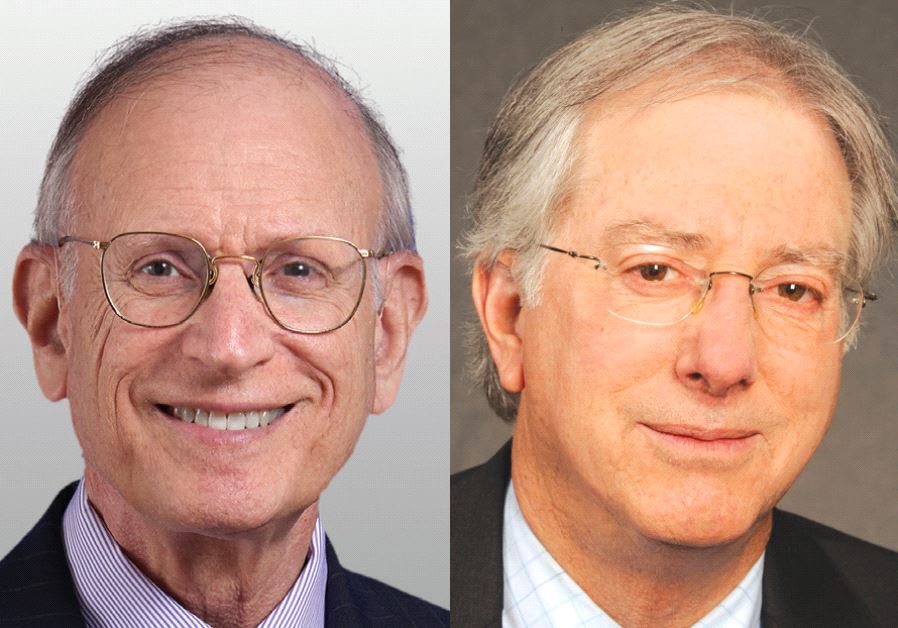

JPPI co-chairman Stuart Eizenstat and JPPI co-chairman Dennis Ross(photo credit: PR/THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE)Updated: Read More

JPPI co-chairman Stuart Eizenstat and JPPI co-chairman Dennis Ross(photo credit: PR/THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE)Updated: Read More