Were the Nazis inspired by US legislation?

Before and during World War II, the US had quotas for Jews in universities and Americans were highly conscious of race.

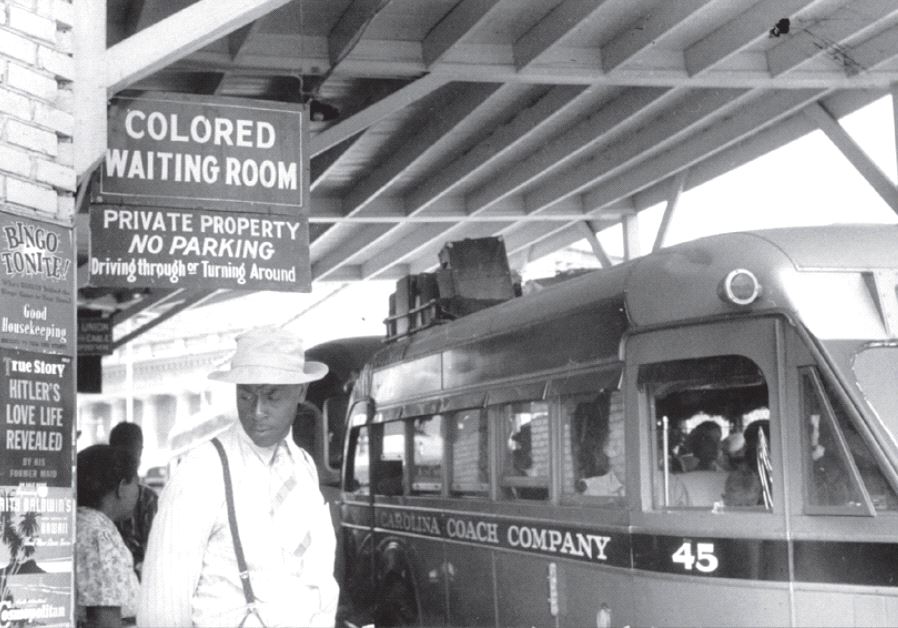

German jurists studied the Jim Crow laws in effect in the southern states(photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

German jurists studied the Jim Crow laws in effect in the southern states(photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)