Hebron matriarch Menuha Rochel still inspires 128 years later

A hundred and twenty- eight years after her death, she is still an inspiration.

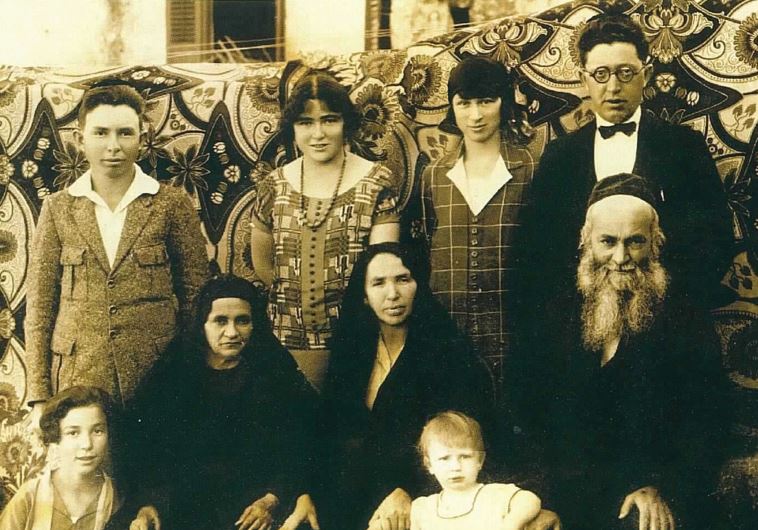

The Slonim family, descendants of Menuha Rochel, before the 1929 Hebron Massacre(photo credit: JEWISH COMMUNITY OF HEBRON)Updated:

The Slonim family, descendants of Menuha Rochel, before the 1929 Hebron Massacre(photo credit: JEWISH COMMUNITY OF HEBRON)Updated: