This Normal Life: Snub from Cairo

Ahmed, our tour guide, clearly didn’t know what to make of us; He definitely realized that something about this typical “American” family was odd.

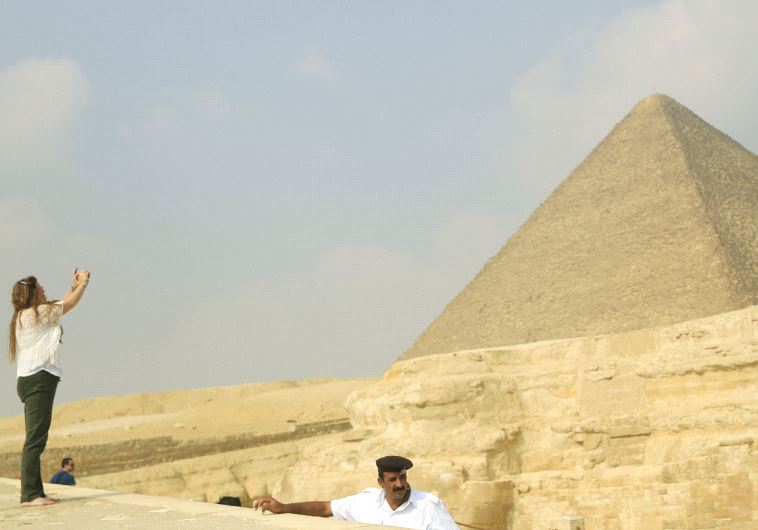

A tourist takes a photo of the Giza Pyramids on the outskirts of CairoUpdated:

A tourist takes a photo of the Giza Pyramids on the outskirts of CairoUpdated: