See the latest opinion pieces on our page

The agreement sets up an aggressive inspection regime. It provides the International Atomic Energy Agency access to all of Iran’s nuclear sites, including the supply chain and any sites deemed suspicious. The IAEA will be able to carry out surveillance at Iran’s uranium mines and mills for 25 years, at its centrifuge production sites for 20 years. And IAEA protocols, which Iran has agreed to sign, provide the agency with additional inspection authorities.Yet, while there are reasons for skeptics to be surprised by what they thought would be a really bad deal, there are also quite worrisome aspects to the framework agreement, the first and foremost being that the Iranians have yet to commit formally to anything of real substance, preferring to postpone signing off until the finalization of the deal at the end of June.In coming days we will probably be seeing the Iranians publicly rejecting elements of the detail-rich US fact sheet, which Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, in a tweet, has already called a “spin.” Even if the key parameters are implemented in full, none of Iran’s nuclear facilities – including the Fordow center buried under a mountain – will be closed altogether. None of the country’s 19,000 centrifuges will be dismantled. Though Tehran’s existing stockpile of enriched uranium will be reduced, it will not necessarily be shipped out of the country.Iran’s nuclear infrastructure will remain intact, though some of it may be mothballed for 10 years. When that period ends, the Islamic Republic could instantly become a threshold nuclear state. Iran will also be allowed to keep an undetermined number of centrifuges at Fordow, though it will not be allowed to enrich uranium. The quality of these centrifuges is unknown. If the Iranians can keep 1,000 high-quality centrifuges intact at Fordow, this could reduce Iran’s breakout time to just three months, according to Scott Kemp, a nuclear expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Another problem is that Iran will be allowed to engage in “limited research and development with its advanced centrifuges” at Natanz, according to the State Department fact sheet. Israeli officials are concerned that these advanced centrifuges could immediately be put into use if the deal breaks down.There is also the question of sanctions. The US had originally hoped for a calibrated reduction in sanctions, in which Iran would have to earn each additional concession. That was seen as a constraint on Iranian behavior, and it was repeatedly stressed by US Secretary of State John Kerry to the Iranians. Though it is still unclear, because information is still fragmentary, the US seems to have softened its terms on this key issue.Not only is no mention made of Iran’s development of long-range missiles that could only be used to carry nuclear warheads, the key parameters are silent on Iran’s support for terrorism, not just in the Middle East but in far-flung locations such as Buenos Aires and Burgas.Indeed, while talks progressed between Iran and the P5+1 (the US, Britain, France, China and Russia plus Germany), Reza Naqdi, the commander of the Basij militia of the Revolutionary Guards, declared that “erasing Israel from the map” is “nonnegotiable.”Ultimately, a nuclear deal with Iran, like any deal, relies on the good intentions of both sides. An expansionist Islamic Republic that is actively involved in nearly every military conflict in the region and that publicly calls for the destruction of Israel is hardly a reliable partner. The skeptics have every reason to remain skeptical.

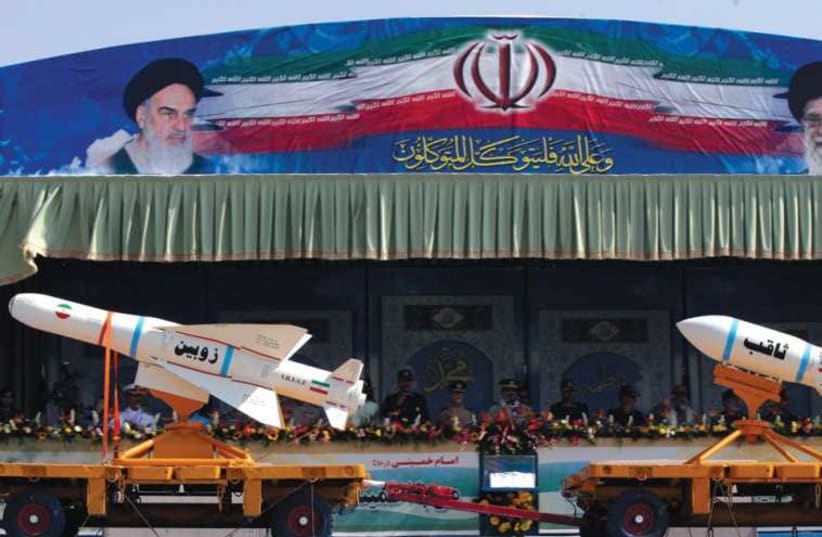

The Iran deal

Many self-appointed skeptics said they were pleasantly surprised by the key parameters for an agreement on Iran’s nuclear program released on Thursday.