A Jerusalem breath of fresh air

A permanent exhibit on interaction among scientific fields has joined the Hebrew University Givat Ram campus’s outdoor displays of nature.

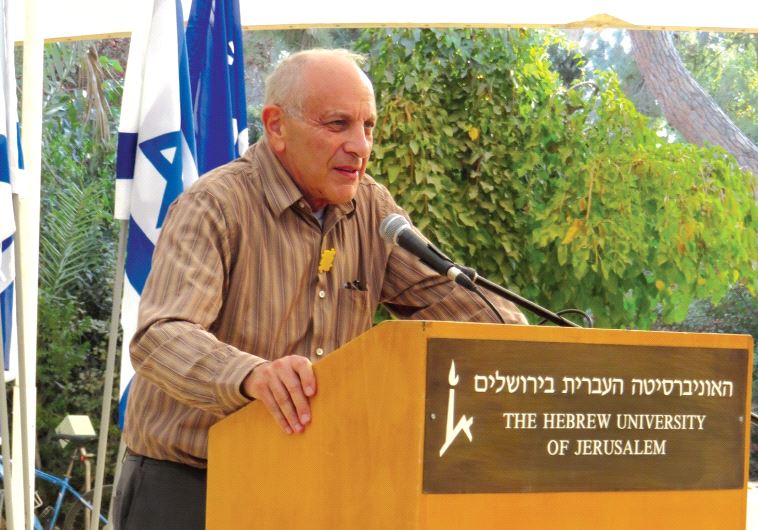

PROF. JEFF CAMI (Kimchi) speaking at the opening of the exhibit.(photo credit: JUDY SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH)

PROF. JEFF CAMI (Kimchi) speaking at the opening of the exhibit.(photo credit: JUDY SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH)