The killers of Yatta

While the small village outside Hebron has produced four people who have attacked and murdered Israelis, a surprising Jewish connection is also found.

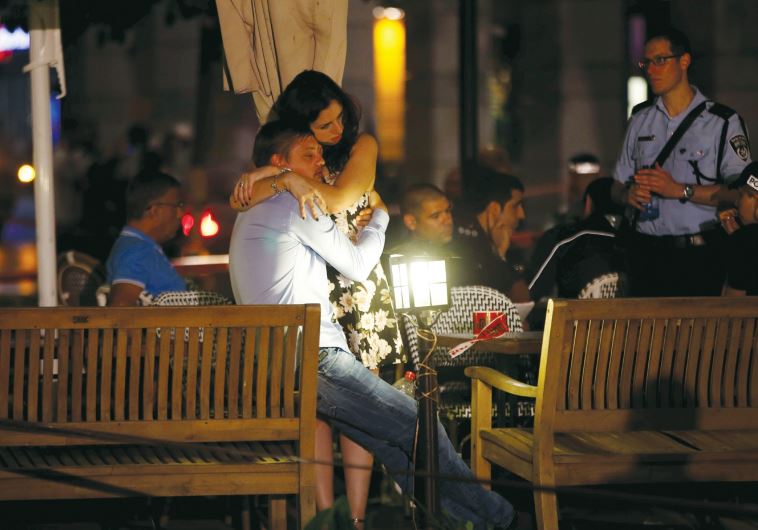

A man and woman comfort each other following the terrorist attack in Tel Aviv last weekUpdated:

A man and woman comfort each other following the terrorist attack in Tel Aviv last weekUpdated: