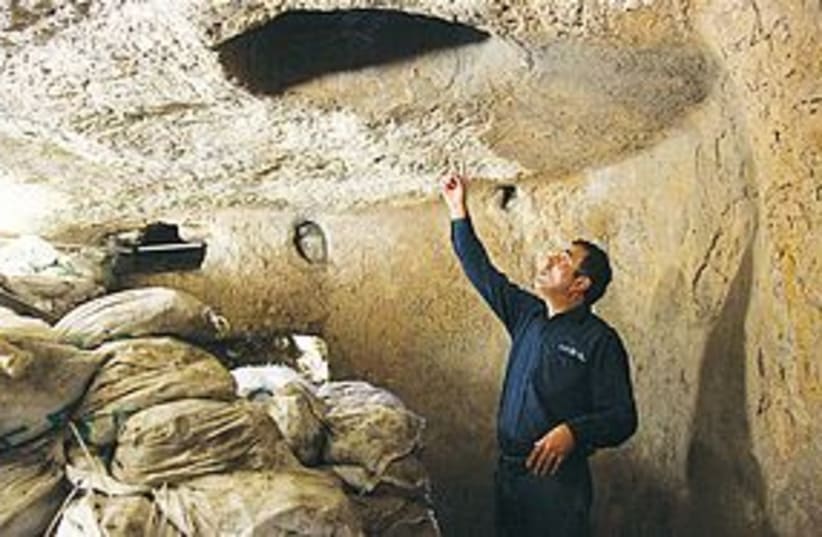

RELATED:Second Temple main street discovered2,000 year-old intact carving of Cupid found in JerusalemArcheological work in the Western Wall Plaza has often led to violence in the past, such as in February 2007, when construction of a temporary bridge to the Mugrabi Gate entrance of the Temple Mount sparked violent protests not just in Jerusalem but across the Muslim world. The Jerusalem police, however, told The Jerusalem Post it was “very quiet” in east Jerusalem all day on Tuesday.The channel was an early drainage system for the city of Jerusalem, which emptied into the Shiloah Pools on the southern end, in today’s Silwan neighborhood. Archeologists believe that the other side of the channel is near Damascus Gate. The channel was extensively excavated more than 100 years ago by British explorer Charles Warren in 1867 and archeologists Bliss and Dickey in the 1890s. The southern section of the channel has been open to the public for many years, but this was the first time that it was discovered that it is a continuous channel, about 600 meters long altogether.Much of the channel had already been excavated by previous explorers, said Eli Shukron, the archeologist overseeing the project for the Israel Antiquities Authority.After additional budget was made available for the excavation work, IAA started excavations seven years ago in cooperation with the City of David park and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority.Shukron led the Post on a tour of the channel following the announcement on Tuesday afternoon. The channel is about 1/3 of a meter wide and ranges in height from one to two meters, and is between 15 to 20 meters underground. The channel’s clearing also allowed archeologists to see the lower stones of the Kotel that are currently underground, though Shukron dismissed the Kotel stones as the least exciting part of the project.“You know the Kotel already; that’s already been overdone,” he said, hurrying past the bottom of the Kotel to point out an underground mikve (ritual bath) and an ancient manhole.“Every rock has a story here,” he said, gesturing to a large boulder in the ceiling. He explained that the boulder had fallen into the arch of the ceiling during the Roman plundering of the city in 70 CE and serves as physical testimony to the violence of the times.“What this gives us is an understanding of the conditions of the roads in Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. How did the city work? How did the city live? Here you’ve got something important, something interesting, something that you can relate to,” he said.Shukron also pointed out the remnants of previous explorations, including old wires and writing on the wall in French. He stressed that the channel did not go anywhere near the Temple Mount or the mosques, in contradiction to some claims. The channel follows the Tyropoeon Valley, which is the lowest area in ancient Jerusalem. “That’s why I can’t go up to the Temple Mount, because the Temple Mount is high. There’s no way that a drainage pipe could reach there,” Shukron explained.The rabbi of the Western Wall, Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz, strongly denounced claims that the channel was an attempt to disrupt the delicate status quo in the area.“No one is digging their way underneath the Temple Mount, both because it’s explicitly forbidden according to Halacha and because it’s simply not possible” he said. “Every attempt to claim that the digging will damage the holy area is an outright lie, whose only goal is unnecessarily and dangerously fanning the flames in a place that is holy to all of the religions.”The NGO Ir Amim has expressed concern about the project over the past years.“Any archeological work of the Old City and its immediate environs is a highly sensitive political issue, not only an archeological issue,” said Sarah Kreimer, the associate director of Ir Amim. “The work should be done with maximum transparency, and in consultation with all of the parties who are connected to the Old City. By carrying out the work in a secretive and non-transparent way, it leaves [room] open for a lot of suspicion and rumors.”She faulted the project for being unclear about the funding of the project and the permits for digging. A few years ago, residents of Silwan appealed to the Supreme Court, accusing the IAA of operating with an incorrect archeological permit that would not allow such extensive excavations. The Supreme Court rejected the petition.IAA acting spokesman Itzhak Rabihiya told the Post that the IAA had received all of the correct permits throughout the seven-year project.Final work on the channel will be completed in the next few months and Shukron hopes it will eventually be open to the public, perhaps as soon as in the next year or two.“This is a part of the story of the city, that there were roads and there were places to park and there were pedestrians,” he said.Even Josephus, the Roman historian who documented the final moments of Masada, describes the importance of the drainage channels, which provided a hiding spot for the last Jews fleeing from the Romans during the siege of the city. The channel has the remnants of pots and living areas, leading historians to believe some Jews hid in the channel for significant periods of time.“The Romans killed some of them, some they carried [away as] captives, and others they made a search for underground, and when they found where they were, they broke up the ground and killed all they met with,” Joshephus wrote.Today, 20 meters below the Western Wall plaza, it’s possible to see the stones that were broken by the Romans as they searched for the last remaining Jews, and to visualize the layout of the city as it stood 2,000 years ago.

2,000-year-old channel cleared under J'lem’s Old City

Western Wall rabbi seeks to soothe tensions by denying that project is really an attempt to excavate beneath Temple Mount.

RELATED:Second Temple main street discovered2,000 year-old intact carving of Cupid found in JerusalemArcheological work in the Western Wall Plaza has often led to violence in the past, such as in February 2007, when construction of a temporary bridge to the Mugrabi Gate entrance of the Temple Mount sparked violent protests not just in Jerusalem but across the Muslim world. The Jerusalem police, however, told The Jerusalem Post it was “very quiet” in east Jerusalem all day on Tuesday.The channel was an early drainage system for the city of Jerusalem, which emptied into the Shiloah Pools on the southern end, in today’s Silwan neighborhood. Archeologists believe that the other side of the channel is near Damascus Gate. The channel was extensively excavated more than 100 years ago by British explorer Charles Warren in 1867 and archeologists Bliss and Dickey in the 1890s. The southern section of the channel has been open to the public for many years, but this was the first time that it was discovered that it is a continuous channel, about 600 meters long altogether.Much of the channel had already been excavated by previous explorers, said Eli Shukron, the archeologist overseeing the project for the Israel Antiquities Authority.After additional budget was made available for the excavation work, IAA started excavations seven years ago in cooperation with the City of David park and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority.Shukron led the Post on a tour of the channel following the announcement on Tuesday afternoon. The channel is about 1/3 of a meter wide and ranges in height from one to two meters, and is between 15 to 20 meters underground. The channel’s clearing also allowed archeologists to see the lower stones of the Kotel that are currently underground, though Shukron dismissed the Kotel stones as the least exciting part of the project.“You know the Kotel already; that’s already been overdone,” he said, hurrying past the bottom of the Kotel to point out an underground mikve (ritual bath) and an ancient manhole.“Every rock has a story here,” he said, gesturing to a large boulder in the ceiling. He explained that the boulder had fallen into the arch of the ceiling during the Roman plundering of the city in 70 CE and serves as physical testimony to the violence of the times.“What this gives us is an understanding of the conditions of the roads in Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. How did the city work? How did the city live? Here you’ve got something important, something interesting, something that you can relate to,” he said.Shukron also pointed out the remnants of previous explorations, including old wires and writing on the wall in French. He stressed that the channel did not go anywhere near the Temple Mount or the mosques, in contradiction to some claims. The channel follows the Tyropoeon Valley, which is the lowest area in ancient Jerusalem. “That’s why I can’t go up to the Temple Mount, because the Temple Mount is high. There’s no way that a drainage pipe could reach there,” Shukron explained.The rabbi of the Western Wall, Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz, strongly denounced claims that the channel was an attempt to disrupt the delicate status quo in the area.“No one is digging their way underneath the Temple Mount, both because it’s explicitly forbidden according to Halacha and because it’s simply not possible” he said. “Every attempt to claim that the digging will damage the holy area is an outright lie, whose only goal is unnecessarily and dangerously fanning the flames in a place that is holy to all of the religions.”The NGO Ir Amim has expressed concern about the project over the past years.“Any archeological work of the Old City and its immediate environs is a highly sensitive political issue, not only an archeological issue,” said Sarah Kreimer, the associate director of Ir Amim. “The work should be done with maximum transparency, and in consultation with all of the parties who are connected to the Old City. By carrying out the work in a secretive and non-transparent way, it leaves [room] open for a lot of suspicion and rumors.”She faulted the project for being unclear about the funding of the project and the permits for digging. A few years ago, residents of Silwan appealed to the Supreme Court, accusing the IAA of operating with an incorrect archeological permit that would not allow such extensive excavations. The Supreme Court rejected the petition.IAA acting spokesman Itzhak Rabihiya told the Post that the IAA had received all of the correct permits throughout the seven-year project.Final work on the channel will be completed in the next few months and Shukron hopes it will eventually be open to the public, perhaps as soon as in the next year or two.“This is a part of the story of the city, that there were roads and there were places to park and there were pedestrians,” he said.Even Josephus, the Roman historian who documented the final moments of Masada, describes the importance of the drainage channels, which provided a hiding spot for the last Jews fleeing from the Romans during the siege of the city. The channel has the remnants of pots and living areas, leading historians to believe some Jews hid in the channel for significant periods of time.“The Romans killed some of them, some they carried [away as] captives, and others they made a search for underground, and when they found where they were, they broke up the ground and killed all they met with,” Joshephus wrote.Today, 20 meters below the Western Wall plaza, it’s possible to see the stones that were broken by the Romans as they searched for the last remaining Jews, and to visualize the layout of the city as it stood 2,000 years ago.