| More about: | Sarit Hadad, Jewish Agency for Israel, Sudan, Ethiopia |

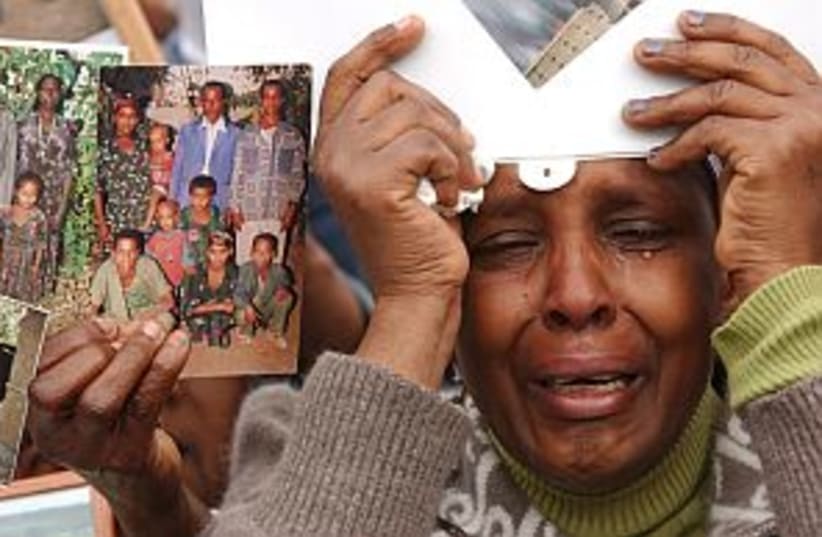

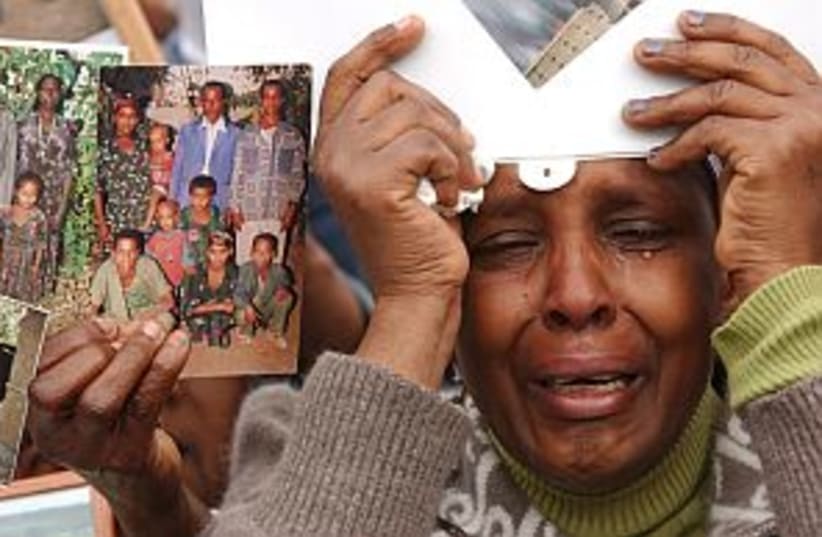

Ethiopian Christian faces deportation

Government demands proof that Dejjan Gavrai helped Jews immigrate.

| More about: | Sarit Hadad, Jewish Agency for Israel, Sudan, Ethiopia |