Montpellier Dance Festival: June 24-July 9

One by one the dancers enter, performing short solos portraying inner landscapes, and soon the compiled effect of the solos becomes overwhelming.

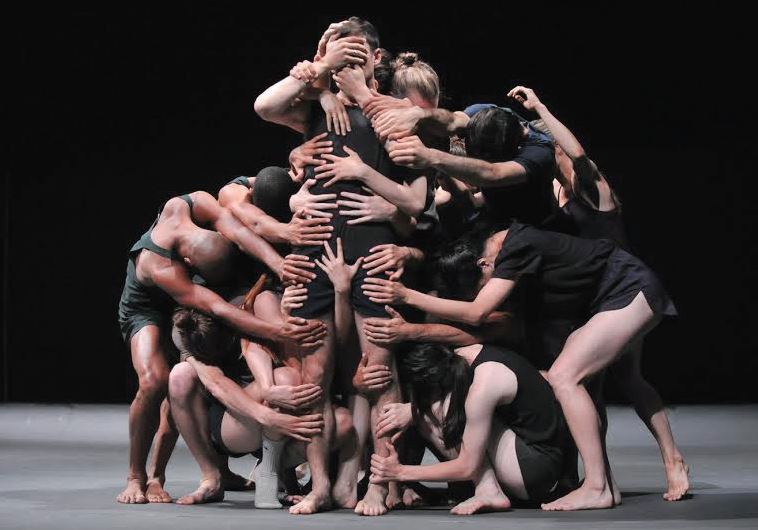

Ohad Naharin's ‘Last Work.’(photo credit: GADI DAGON)Updated:

Ohad Naharin's ‘Last Work.’(photo credit: GADI DAGON)Updated: