The Lilliputians in Swift's Gulliver's Travels may have been speaking Hebrew

Linguist links nonsense language to Hebrew in Swift's classic of English literature.

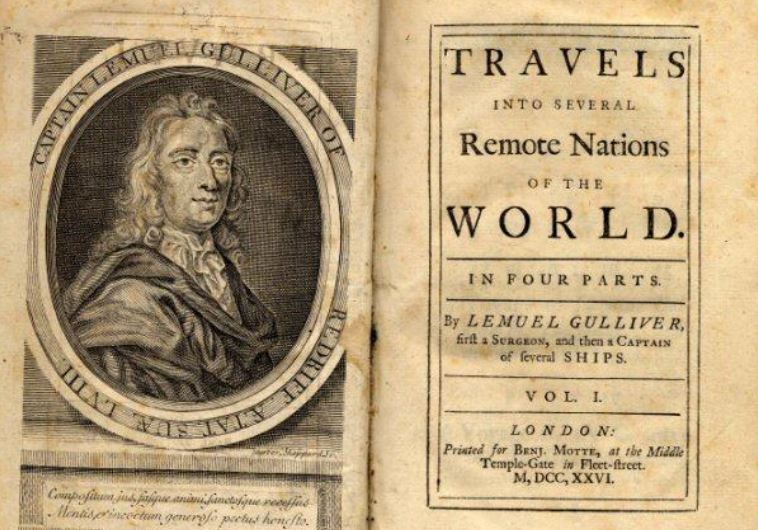

Title page of first edition of Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift. (photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)Updated:

Title page of first edition of Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift. (photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)Updated: