Decision-making at times of war and peace

Former NSC chief Uzi Arad’s decades-long battle over the past and future of the National Security Council.

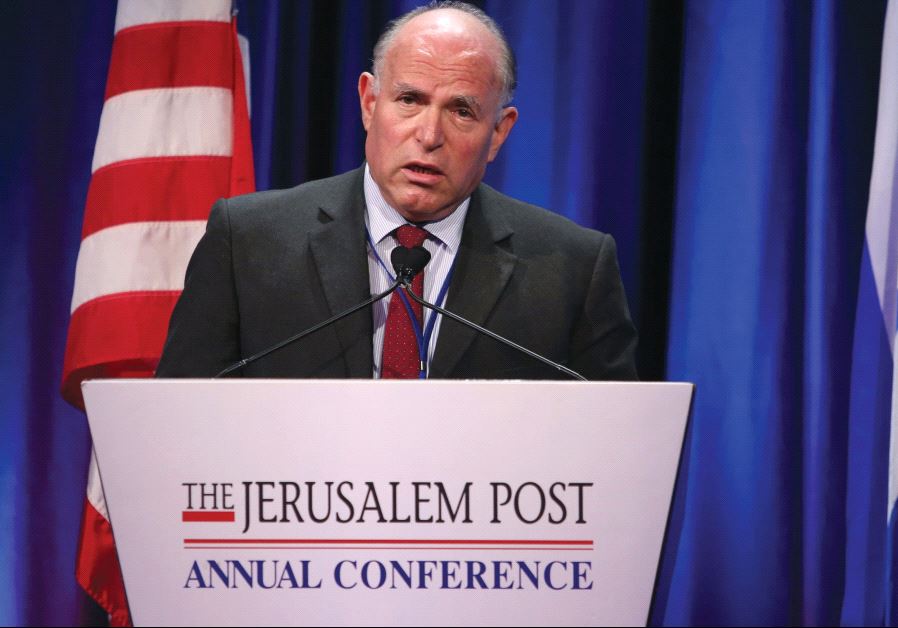

FORMER NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL chief Uzi Arad.(photo credit: MARC ISRAEL SELLEM/THE JERUSALEM POST)

FORMER NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL chief Uzi Arad.(photo credit: MARC ISRAEL SELLEM/THE JERUSALEM POST)