Borderline Views: Remembering Rabin – peacemaker or assassinated PM?

He was, also, the prime minister that signed the Oslo Accords, signaling a structural change in the way that Israel related to the Palestinians.

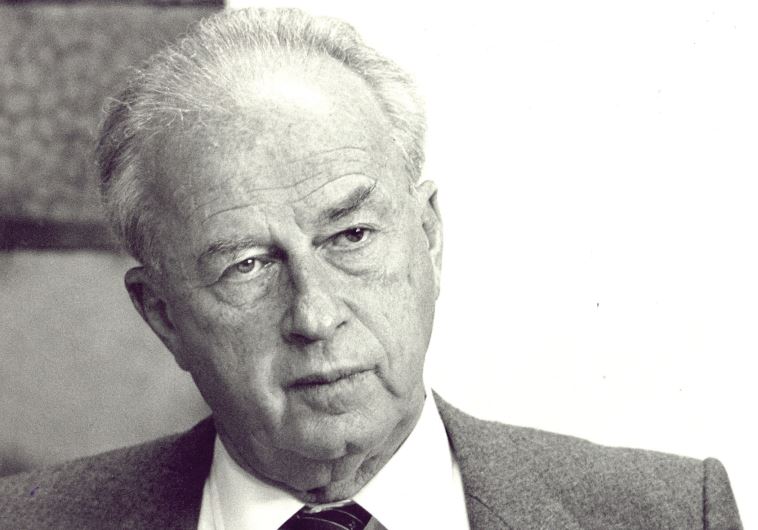

Yitzhak Rabin in 1985, then defense minister(photo credit: DAVID BRAUNER)

Yitzhak Rabin in 1985, then defense minister(photo credit: DAVID BRAUNER)