Helping lone soldiers find their feet

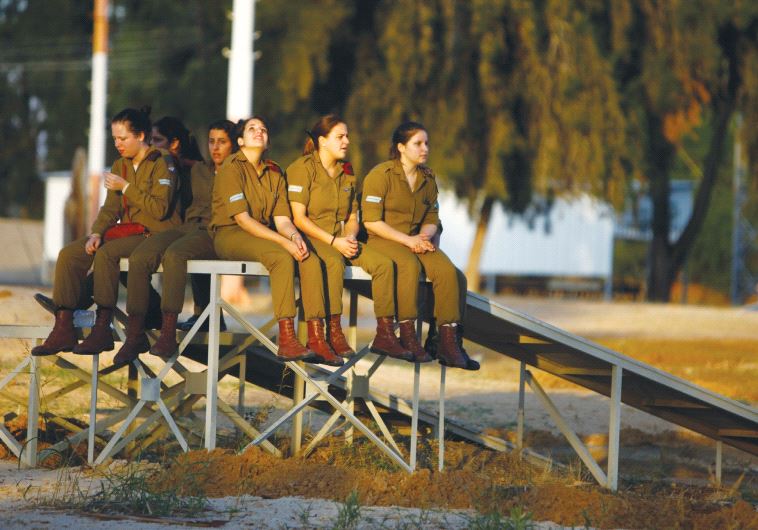

This is the life of a Lone Soldier, someone who gives up the familiarity of everything they know to defend their ancestral nation.

A FAREWELL to arms. What happens after it’s over? For the lone soldier, it can be difficult.

A FAREWELL to arms. What happens after it’s over? For the lone soldier, it can be difficult.