Terra Incognita: Israel is at its most and least integrated moment in the Mideast

Israel was always going to be a janus-faced country because of its nature.

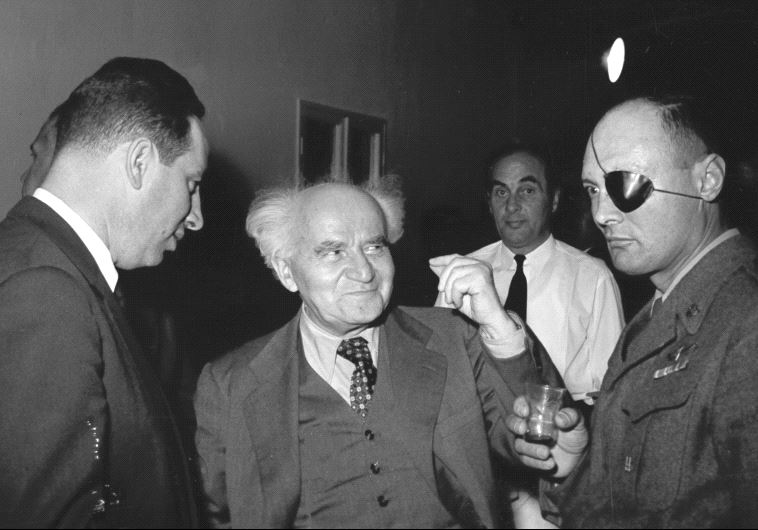

From Left: Shimon Peres, David Ben-Gurion and Moshe Dayan(photo credit: AVRAHAM VERED / IDF AND DEFENSE MINISTRY ARCHIVES)Updated:

From Left: Shimon Peres, David Ben-Gurion and Moshe Dayan(photo credit: AVRAHAM VERED / IDF AND DEFENSE MINISTRY ARCHIVES)Updated: