What remains of Ararat

There might have been more to Ararat than benevolence. Noah saw a personal economic opportunity in a major real estate bonanza.

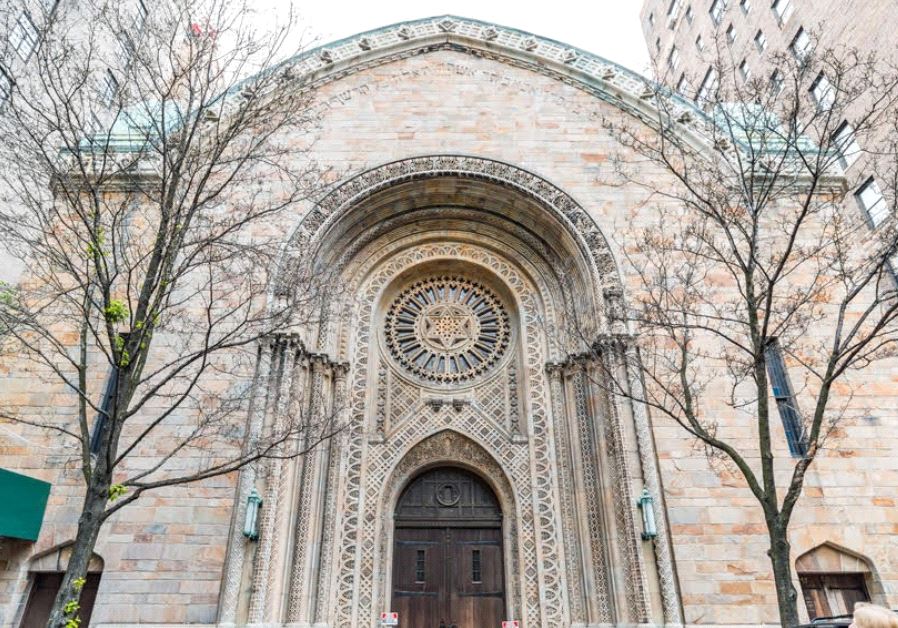

The entrance to B’nai Jeshurun on West 88th Street in New York City(photo credit: COURTESY OF B’NAI JESHURUN)

The entrance to B’nai Jeshurun on West 88th Street in New York City(photo credit: COURTESY OF B’NAI JESHURUN)