Yeshayahu Leibowitz: Idol smasher or idol maker?

The brilliant Yeshayahu Leibowitz – one of the most admired and the most despised thinkers in the history of the State of Israel.

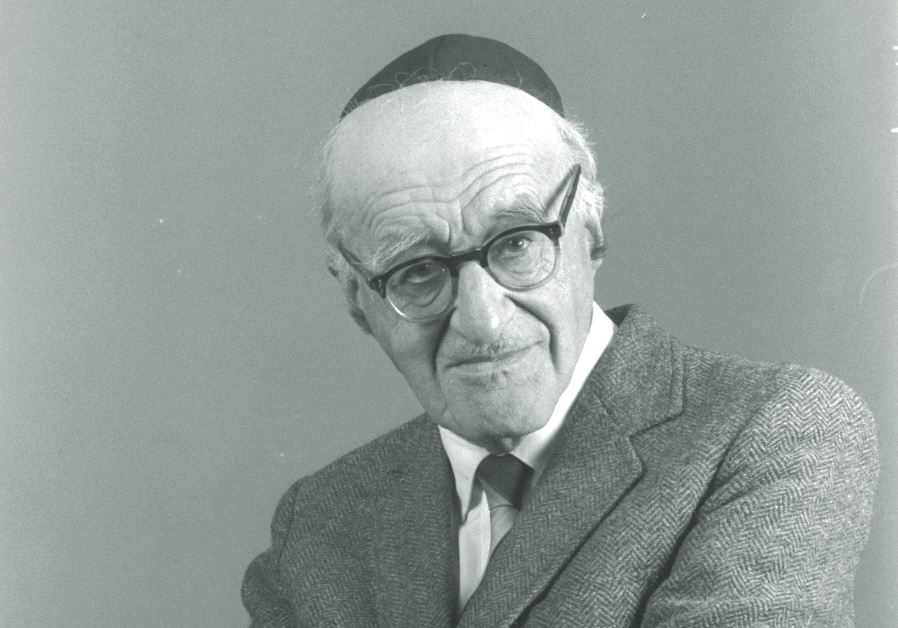

Prof. Yeshayahu Leibowitz: An unattainable path(photo credit: SA’AR YA’ACOV/GPO)

Prof. Yeshayahu Leibowitz: An unattainable path(photo credit: SA’AR YA’ACOV/GPO)