Into the half-calculated chaos of a student protest, Jacobo follows a charismatic leader and “a girl with skin like a young western honey mesquite.”

Novelist David Hirshberg has chosen to take him in from an unusual, not fully modern community with origins even more exotic than the neighboring Navajos. “You couldn’t find it on a map, there were no records in the county archives, and we buried our dead without permits, up on a hill, from which you could see both the mountains to the west and the Rio Grande to the east.”

In his childhood, Jacobo hears myths from his father which involve ghastly medieval-sounding dangers and which end in rescue by a self-sacrificing humanoid called the Holyman.

After such a beginning, Jacobo’s Rainbow can count on the reader to accept some more mildly farfetched ideas such as a secret passage into the basement of a university building that the student protesters have taken over. The invaded building belongs to the University of Taos, near New Mexico’s border with Colorado.

Hirshberg’s name is a pseudonym but the publisher’s own publicity on the web doesn’t conceal his real name. He was in college during the Johnson administration in America, and sets Jacobo’s Rainbow during those years; as an alumnus of similar age, I can confirm that Jacobo’s point of view – as a new kid among the college radicals – is authentic.

Like the protagonist of Hirshberg’s debut novel, My Mother’s Son, Jacobo is involved in the action as a kind of junior participant, an apprentice or protégé. He is not uncritically committed, and a firm-armed friend named Herzl shares his reservations.

What do the rebelling students really want? “Thinking back on it now,” says Jacobo, “this might’ve been the first time I’d experienced a situation in which I had to evaluate someone’s motives as opposed to simply accepting their actions at face value. I was on that cusp between childhood and adulthood.”

The leading student activists are a firebrand named Myles and his mutually abusive girlfriend Claudia. Also present for the seizure of the university building is Mir, the honey-skinned girl, along with Jacobo, who – like his biblical namesake – is a dreamer.

The other followers are less of a vivid presence in the book, so that on the one hand telling the characters apart isn’t too difficult, but on the other hand the realism surrenders a bit to a dreamlike selectivity of focus.

The novel’s dialogue too could be described as dreamlike, as a way of excusing occasional words or constructions that aren’t normally heard from real people in real life. For example, there’s Herzl describing Fridays at the school cafeteria of his youth: “‘If you can believe it, these guys took out their antipathy toward fish on me,’ he said. ‘And recess was something to be feared, as they’d wait for me and pummel me with food and fists.’”

And after Jacobo leaves college, the way the narrative jumps months into the future, ignoring much that must have happened along the way, is as quick and smooth as a dreamer’s change of scene.

At that point, Jacobo meets another ally and his name is Hank. Hank seems to complete a trio of protectors for Jacobo, following the mythical Holyman and the formidable companion Herzl.

Herzl’s name goes unexplained for a while, but once the novel has made some progress in capturing the reader, explanations emerge and so does a heartfelt element of the novelist’s agenda. Jacobo discovers that he knows more Jews than he realizes. Why hadn’t he recognized that “Ben Venisti” means “the son of Venisti”? (Well, it doesn’t. Maybe that’s Jacobo’s mistake but I wish I could be sure it isn’t the author’s.) And Hirshberg draws a bold line connecting the Free Speech movement on the college campuses of the 1960s with communism and antisemitism.

Clearly, the reader is meant to see today’s campuses and today’s political intersectionality reflected, if not rooted, in the ‘60s, with Herzl’s girlfriend Mir complaining that “an antisemite can hide behind the curtain of anti-Zionism and not be accused of being a bigot.” Mir suffers from cancel culture, not yet known by that name, as a news report she has submitted to a local paper about goonish anti-war demonstrators is spiked.

The politically motivated squelching of the news report is all the more painful because previously Mir’s coverage of the student uprising at the University of Taos had been snapped up by Life magazine.

By reminding us that well-intentioned idealists were sometimes duped half a century ago by intolerance masquerading as high morality, it warns us that similar intolerance is once more entrapping the college kids.

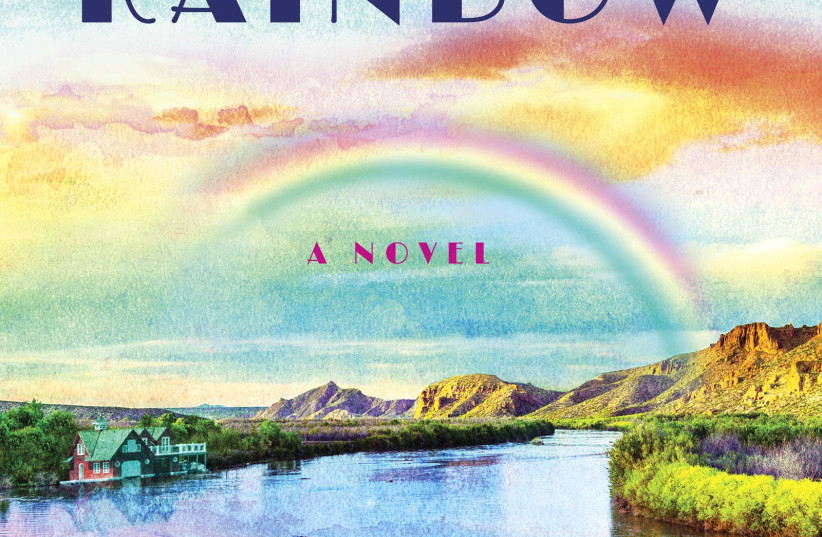

JACOBO’S RAINBOW

By David Hirshberg

Fig Tree Press

340 pages, $19.95