Presumably we will be referring to, if not harping on about, this coronavirus age and its implications for many a year hence. And while it has become, to say the least, a tiresome subject, the fallout thereof is also having some intriguing impact on the work of artists across the globe.

For nigh on six decades, the Jerusalem Artists’ House has made a habit of putting some envelope-pushing stuff out there, featuring established artists and newcomers taking their first collection steps alike. The new four-parter runs a broad gamut of styles, cultural and ethnic baggage, disciplines and social intent.

Jerusalem Artists’ House director Ruth Zadka observes that the latter stood the artists, and their presentation, in good stead as the pandemic, and accompanying official strictures, wore on and on. “I can’t tell you how many changes we have been through while we waited to see when we could actually reopen,” she says. Zadka was not just talking about the logistics of getting back to work and opening the doors of the century-plus old edifice on Shmuel Hanagid Street, once again, to the public.

“This synergy has been developing for over a year and a half, long before the pandemic, and the installation changed time after time,” she adds as we enter one of the larger display areas, the majority of which is taken up by a pinkish skin-colored dress on a headless manikin, with a train that snakes several meters across the floor tiles. “It’s a bit Hellenistic,” Abergel proffers although, personally, I couldn’t see the connection with the realist sculptural school of thought that was all the rage in Greece and the regions it conquered and impacted on for three centuries, from the late 4th century BCE. Then again there is definitely something statuesque about the figure, and the puce colored material does put one a little in mind of a marble texture.

There are some intriguing conceptual and biographical junctures in “Prestige.” The title, for starters, infers the improbable juxtaposition of two seemingly disparate worlds. “One of the things that Marcelle and I relate to is the place of fashion, and chic, which is very present in the haredi world, with all its [social] codes,” Dery explains. That, I suggest, would come as quite a surprise to many secular Jews, and others, who presumably equate haredi apparel with a strictly conservative monochromic mindset.

Dery says she and Bitton were conscious of the inaccurate stock view of their community by outsiders, and were keen to set that to rights. “That is why we wanted to bring the nuances to center stage, not just the so-called black and white aesthetic.” Dery dips into her own bio. “I think of my grandmother, who made aliyah from Morocco. She was chic personified,” Dery laughs. “She was into Dior – which has a strong presence here – creams and clothes, and she spoke French to her children.”

She took no little stick for her sartorial predilection. “People made fun of her. They said she was a snob, and why didn’t she speak Moroccan. It was only after she died that I realized how much fashion and finesse were important to her, even with all the socioeconomic challenges they had to face here, after leaving their comfortable life in Morocco behind.”

Dery and Bitton employ a multisensorial approach to conveying their personal and artistic message. One of the rooms features a long, slender glass-topped display table which holds dozens of oddly-shaped narrow-necked glass containers partially filled with aromatic liquids that traverse a gradated color spectrum that works its way from yellow and amber through to pink and variants of red. That is yet another nod to feted French fashion designer Christian Dior, and the world of haute couture in general, and serves to convey the hitherto little known interest in haredi women’s circles in stylish threads and accessories.

“It reminds you of a means of display, or a memorial table,” Bitton explains. “You know, when there is an azkarah (anniversary of the passing of a family member), people gather to remember the deceased, and to eat and be together.”

Dior comes into view yet again. “Dior had this range of perfumes which was very distinctive,” Bitton continues, adding that the exhibition furniture was inspired by similar real commercial world furnishings. “Quite a few of Christian Dior’s stores had a table just like this, with a very concentrated perfume series. The series is called Maison Christian Dior, the House of Christian Dior.” That brings us back to the domestic theme that runs right through “Prestige.”

In truth there are quite a few threads in the installation seams. “These two artists both have a deep knowledge of the Torah, the Kabbalah and other religious material,” says Zadka. “There is this fascinating interwoven mix between that and the outside world, art and fashion.”

There is indeed, complemented and enhanced by some alluring, and even tongue-in-cheek visuals. One wall sports a highly individual reading of a classic Dior print starring Bitton in a trademark Dior getup, flowing floral dress, delectable high-heeled shoes and all. Therein also lies some feminist intent, which crops up across the work. “I am there measuring the costume,” Dery notes. “That is a role which was normally taken by a man.”

Fans of late British actress Audrey Hepburn and, in particular, one of her best-known pieces of celluloid Breakfast at Tiffany’s should get a kick out of the 12-minute, four-scene video the artists duplicated from the 1961 romantic comedy. They simply transplanted the action to Mea She’arim, pretty seamlessly, with Bitton in Hepburn’s character of Holly Golightly even sporting some Givenchy-style headgear. It makes for fun viewing.

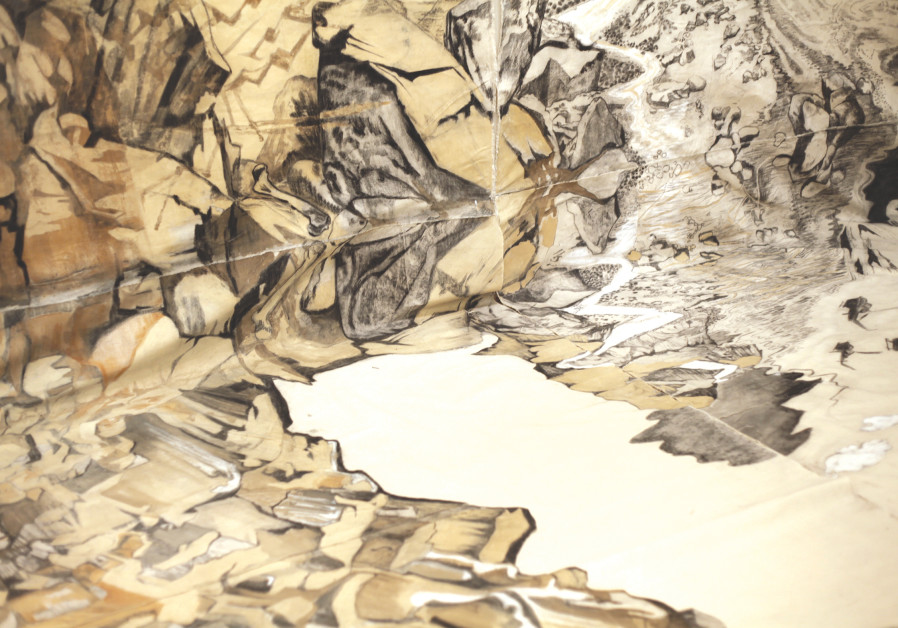

NETTA LIEBER SHEFFER’S site-specific “Six Extremities” is a very different kettle of fish. There is much to take in there and the cloth-based installation has one looking every which way, suddenly espying a stairway leading nowhere in particular, a cascading pile of rocks or a river lazily meandering its way through a valley. There is a sense of chaos which, Lieber Sheffer explains, portrays something of the way we live in these increasingly technology-monitored times.

In fact, the artist dips into art history, and digs out an exciting visual innovation from the 18th century to get her highly contemporary message across. “This is a sort of tribute to the panoramas of the 18th and 19th centuries – cyclorama is a more accurate term – which created illusions. That was the main form of mass entertainment before the cinema.”

The first purpose-built cyclorama was created by Irish painter Robert Barker as a way of capturing the 360 degree view from Calton Hill in central Edinburgh, Scotland. The first cyclorama building was opened there in 1787.

Fast forward a couple of centuries or so and we have a very different zeitgeist to ponder. “I wanted to show something from the 21st century without relating to a specific place or a particular event. It is entirely a sort of cut and paste effort, with excerpts from here and there, from the past and present.”

The Lieber Sheffer cyclorama vehicle has the hall shrouded in cream-colored canvas with shapes and scenes drawn using tints that vary between earthy browns and black. It is a pretty organic base. “I use soil from three different parts of the country and, of course, charcoal,” she says. “I wanted to have a natural feel to the work.”

The data-suffused era in which we all live today informs the busy layout but, as curator Shlomit Breuer chillingly notes, an ulterior motive lurks. That is nothing new. “People were looking to channel the public’s consciousness, just like they do today. There are all those technological means for doing that today.”

There may be a feeling of pandemonium in the array of images, and incongruous interfaces, but Breuer feels there is some rationale to the visual bedlam. “It is a sort of map. Today everything is mapped out. That also comes into this.”

The public will be invited into the space and to walk betwixt the images. It will be interesting to see how visitors take it all in, and how they cope with the concentration challenge presented by such a multifarious seemingly illogical eyeful.

HANA JAEGER’S niftily named “Wait Times are Longer than Usual” spread of paintings, curated by Dan Orimian, convey a feeling of morbidity and isolation, and possibly a sense of impending doom. Many of the characters depicted shy away, or detach themselves, from the world around them, preferring to retreat into their hoodies, or shut out the sounds of actual life around them with the help of earphones. That is a pretty quotidian element of life, with so many of us keeping the world – which we may construe as being threatening – at bay. Even before the virus made its way across the world, large numbers of public transport users donned earphones or headphones and/or buried themselves in their cellphone screens. Today, more than ever before, there is a tendency to looking inward rather than focusing on and, possibly by definition, opening ourselves up to the perils that may lay out there.

That introspective hideaway element is also front and center in Shir Handelsman’s “Born, Never Asked’ installation and video diptych, curated by Nira Pereg. And, while that may conjure up depressing thoughts of lockdown and a lack of freedom of movement, Handelsman says he gained much insight from the enforced confinement. “I am a basically optimistic person, and I am always on the lookout for new things, and positive things, in life,” he laughs.

That comes through patently in his entertaining video work “Who Owns the Sun?”

“My home also became my studio and, being shut away there, I started to look outward, to see how I can access the outside world even though I can’t be there physically.”

Sisyphus would have identified strongly with the intrusively percussive Stress Fractures mechanized sculpture. The well-named, double entendre and all, work comprises a 150 kg. slab of limestone with five hammers hacking away at it, driven by an electrical mechanism buried in the base. It seems like a pointless exercise and offers a stark counterpoint to the video.

“This is not really effective,” Handelsman remarks philosophically. “The hammers are working away without really bearing fruit.” A parable on everyday life? “Definitely,” the artist concurs. “Then again, look at this,” he says, referring to a small pebble-sized piece of limestone that detached from the rock, even at this early stage of the sculptural dynamics. “Who knows what will happen to it over the next two months?” Hope springs eternal.

Zadka has done her institution, and the public, proud with this impressive lineup of works which should make for gainful, pleasurable and stimulating viewing through to May 22 – pandemic and political shenanigans permitting.