TAU art gallery explores roots of 'selfie' phenomenon with 'Prima Facie' exhibition

The Prima Facie exhibit at Tel Aviv University highlights leading international and Israeli artists’ different approaches to portraiture.

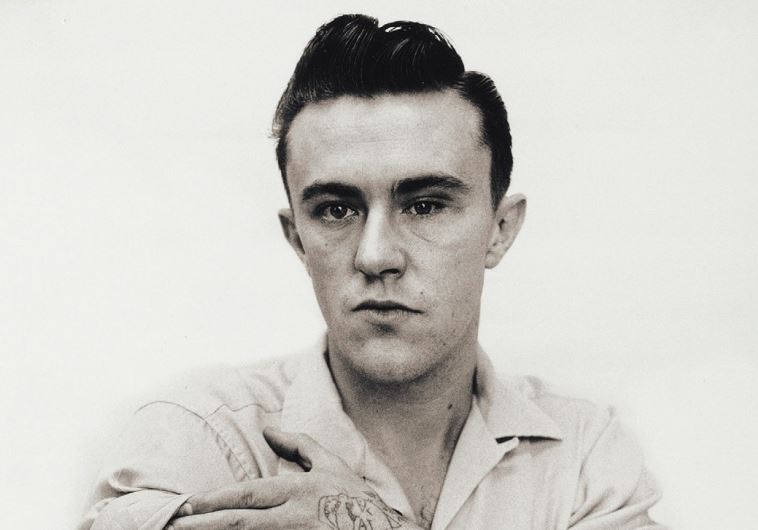

Dick Hickock, Murderer, Garden City, Kansas, April 15, 1960. (photo credit: RICHARD AVEDON)Updated:

Dick Hickock, Murderer, Garden City, Kansas, April 15, 1960. (photo credit: RICHARD AVEDON)Updated: