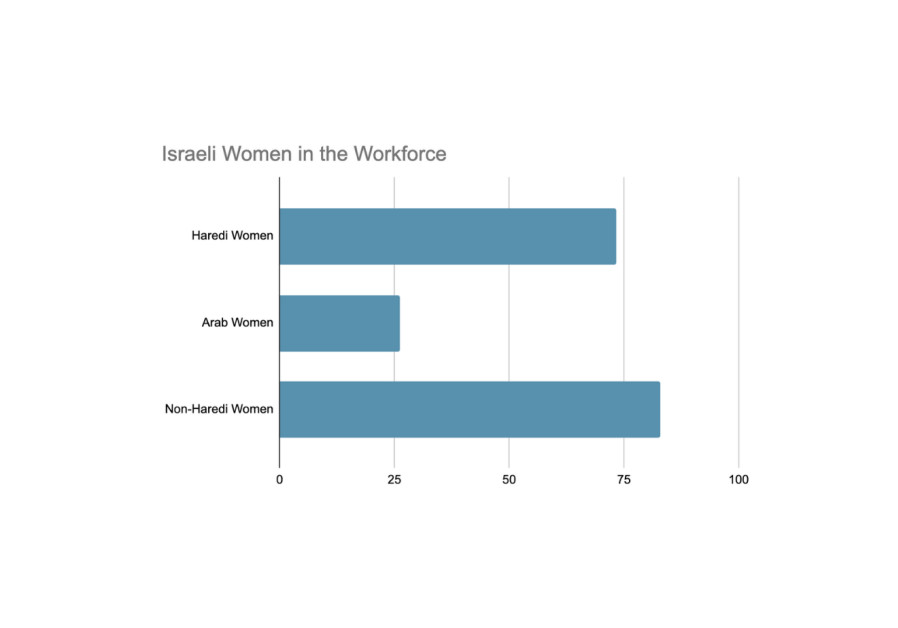

This is fascinating as 83% of non-haredi women are employed in Israel, making the employment difference between haredi and non-haredi women not overly drastic.

Haredi women, often the breadwinners in their households, are employed across a range of industries and cities, and the history of these women in the workplace spans several decades. Following the Holocaust, haredi men felt that haredi longevity was dependent on lifelong learning of Judaism, and therefore increased their devotion to full-time study – something their wives would have to fund and support. This led to women becoming the breadwinners in their families. As a result, according to the Israel Democracy Institute, by the 1990s, two-thirds of haredi women were employed.

In terms of industry distribution, a 2015 survey from the Central Bureau of Statistics revealed 44% of haredi women worked in education, making it the most favored industry. In second place was health, welfare and social services at 19%.

It is unsurprising that haredi women are largely employed in education, as haredim often train women to become teachers within haredi schools. Nevertheless, according to this 2015 survey, many haredi women have been flocking to the burgeoning tech and start-up sector. From 2014 to 2018, the tech industry saw a 52% increase in haredi women workers (the tech industry itself also greatly flourished during these years, possibly accounting for this rapid increase).

Those in education generally both live and work in cities where haredi schools are present. However, some haredi women commute to Tel Aviv to participate in the tech world.

While cultural shifts within the haredi world could account to some degree for these employment trends, a 2003 reduction in child allowances also helped contribute to further the increase of women in the workplace. Moreover, since haredim emphasize large families with men as lifelong learners, women often serve as breadwinners and mothers simultaneously.

“THE PARTICIPATION rates of Arab women are low relative to those of Israeli Jewish women,” according to Volume 10 of the Israel Economic Review. Although the participation rate of Arab women in the workforce “doubled between 1970 and 2010 – from 10% to 20%,” it remains low compared to Jewish women.

When looking at women in the workforce there is a clear disparity between Jewish women and Arab women. Now only 26.3% of Arab women are integrated workers in the labor market, according to research done by Dr. Hanna Hamdan-Saliba and Adv. Gadeer Nicola from Kav LaOved.

This low statistic can be attributed to a number of factors – from Arab fathers working more than haredi fathers and cultural differences that prize the Arab woman’s role as a mother. Furthermore, the lack of public transportation services to and from some Arab towns to workplaces as well as less-than-adequate childcare options also contribute to this situation.

As Israel exits the pandemic and the economy continues to flourish, it will be fascinating to continue to track the employment trends for women from all sectors.