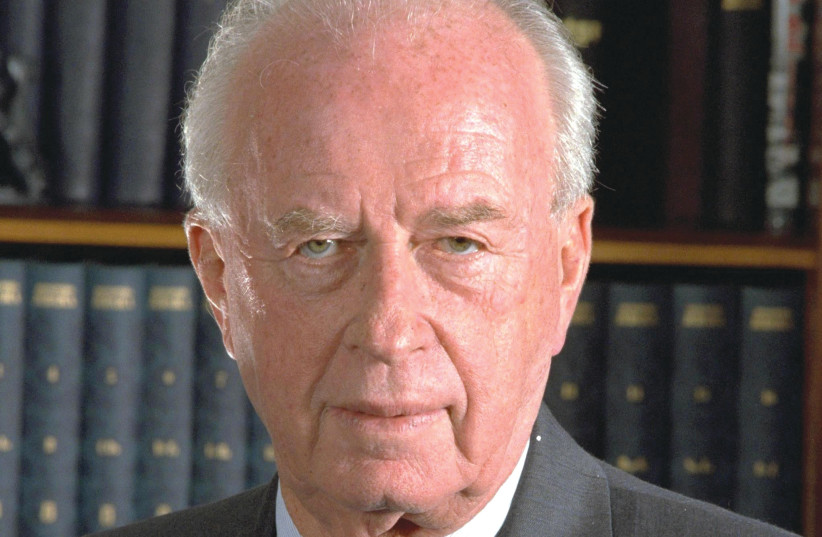

The facts are well-known. On November 4, 1995, Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin was gunned down by an anonymous Israeli Jew, Yigal Amir, at the end of a huge demonstration in the Malhei Yisrael Square (now Rabin Square) in Tel Aviv. The demonstration was in support of the Israeli premier for his efforts to make peace with the Palestinians and specifically for the signing of the Oslo Accords. The assassination was met with almost universal shock and incomprehension. That a Jew – a religious one at that – could kill the elected leader of Israel in cold blood was going to take a long time to absorb, if ever.

Now, 27 years on, this shocking event is in danger of being forgotten. Proof? For the 70th anniversary of Israel’s Independence Day, a presentation was released by the Education Ministry of the government under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu, highlighting major events in Israel till then. The assassination was not mentioned or even hinted at. Moreover, half of Israel’s nine million inhabitants were born after that event. How would they remember Rabin’s murder if at all, especially when their elected leaders did not mention it?

Enter Danny Paller. Musician, theater maven, politically engaged. American by birth but Israeli by choice.

“I had done a number of projects,” he says, “but when I thought about it I said to myself none of them have really been personal, none have been about how I feel about things. I had written a Purim play (a rock opera, translated to Hebrew and aired on TV), a comedy about Jerusalem, a play about two women pirates. They were all interesting pieces, but my heart was not really in them. I wanted something that was connected to who I am.

“Then I thought about the assassination of Rabin, and it appealed to me on many levels. It was a very dramatic time for us. It happened in the week my wife gave birth to our first daughter. A few days later the assassination happened. So it was like emotional schizophrenia. It was one of the pinnacles for us as a married couple – the birth of a child, the investing in the future – and simultaneously this traumatic event. It was horrifying, although at that time we didn’t know how ‘successful’ this assassination would be. As it turned out there were many things that could be, or were, attributed to that event: to the collapse of the Left, to the shift of the country to the Right, and so on.

“So why did I return to that moment? I never thought of leaving Israel. But as time goes on, I feel that I have compromised elements of my soul and my aspirations for this place. Now I could put my finger on that moment when the compromise began. You saw what we were capable of as a society.

“I wanted to write something more personal and that was the moment. I wanted, too, to write for the generation that came afterward. Part of our wishes is that we’ll bring this to the schools and gap-year programs, offer ways in which the younger generation could deal with this event. In many ways, the youngsters are so innocent. They don’t know what was the potential, let alone what devastation was caused by this one act. But for those of us who experienced it, we were aware that something had changed in society. There is a value in going back, naming it, touching it, owning it. It is part of our story, it is part of who we are. If you want to build anything here, you have to acknowledge that there are forces like that and that there are people like that. Against seeing what this society has achieved and can still achieve, you have to look at this dark side. You have to go there.”

Paller found a suitable partner to write a full-length play in Myra Noveck. She had written a number of screenplays that showed that she was a very astute observer of the political situation of the country. She did the historical research and wrote the story with Danny.

“She is also a storyteller,” observes Paller. “Myra and I teamed up. It was a real joint effort. We agreed for all the same reasons, the main one was that you have to look at the dark side of our society. The key question for us was how to tell the story. We did not want this to be a polemical piece, one way or the other. We wanted everyone to see themselves in the mirror. All the voices of that period had to be made relevant. We wanted to get into the head, mostly of Rabin and Yigal Amir, but also Hagai, Amir’s brother, and Noa, Rabin’s granddaughter. They are real people. You meet them, hear them, see them; it’s their drama. You’re stepping into a story that is both a family drama but also a national drama.

“In many ways they mirrored who we were: the people. The way the cabaret is set up, it’s very much a collision course. Early on you get to see them, and as the drama proceeds, the tension between who Rabin is and what he represents, and Yigal Amir and his thinking. It’s a tension that comes to a head. We tried to put a lot of nuances in that would give you a sense of how complex the situation was. Some of that is expressed in the staging, some of it in the lyrics, some in the texture of a song.”

The production, titled NOVEMBER, is billed as a musical drama on the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin and “a collision course between its two main characters – warrior-turned-peacemaker Yitzhak Rabin and his assassin, 25-year-old law student Yigal Amir. It delves into the psyche of a deeply divided country, and explores issues very much at play in our contemporary world: polarized political discourse, demonization of the Other, the role of incitement, the battle between hope and fear.”

The first reading of NOVEMBER was held in Jerusalem in November 2016. Running about two hours, Act I takes place during August-October 1995, and Act II on November 4, 1995, the day of the assassination. The mostly musical play is based on true events that inspired the book and lyrics by Danny Paller and Myra Noveck, with music composed by Paller.

This was not the first attempt to make a public statement in an artistic form about Rabin’s assassination. There was a film in 2020 titled Yamim Nora’im (in English it was called Incitement), although it focused mainly on the biography of Amir. It had been very controversial, critics believing that it humanized Amir. Paller found something similar: “We had people who did not want to participate in the play because Yigal Amir is on the stage. We humanize him. Our take is that these are not monsters, these are people. They have to be seen as people.”

The play went through a number of transformations.

“Originally we wrote it in English, and there was as much dialogue as song,” recalls Paller. “Songs were very important for the emotional sense, and for the nuances of character development. But when we did a reading in English, we realized that we really wanted to do it in Hebrew for the sake of the intended audience. It has to be an Israeli work. I found a translator, Shahaf Ifhar, and once we had it in Hebrew we looked for a director.”

The director they found, Erez Hasson, was already known for his unconventional approach to the stage. He turned the play into a cabaret, making it necessary to cut out most of Noveck’s dialogue, while keeping the architecture – the “bones” – of the story that Noveck and Paller had developed. He also took out men’s roles, making it an all-female cast.

Didn’t Paller think it was peculiar to present such a tragic event through a cabaret? Surely it deserved something more serious.

Paller is adamant: “Some of the greatest music in the world is around tragic events. Half of opera, for example. I was groomed on Stephen Sondheim musicals. My favorite work of his is Sweeney Todd, which is about cannibalism. Cabaret is pushing the envelope as far as it will go. One of the things this shows is what muscle music has for creating theater and telling a story. But it also challenges an audience.

“We have four women who show up at the theater. None of them is Rabin or Yigal Amir. They’re four women and they take on a role and then come back to their table and have a drink. It’s a cabaret evening. All four of these women play all of the characters. There are no men, and there is no assignment of an actor to a role. They all play all the roles.

“One of the reasons is that from the get-go, we wanted to eliminate the conventional thinking that says that Rabin had a lower voice, or that Yigal Amir wasn’t very tall. This is not about that. In the movie, an actor played Yigal Amir and looked a little like him. We negate all that. This is about storytelling. These are women telling a story. They step into a role, and then they step out of it. You buy it, because that moment is happening and that moment is dramatic. This is part of what we want, in order to make it dramatic and surprising.”

Despite the theatrical handling of the story, Paller insists that: “It’s all based on facts. The reason that it works as theater is because the audience is emotionally involved. Ultimately it is them on the stage.”

Paller is helped in his production by a group of professional actors with a wide range of experiences in professional theater, from musicals at the Cameri Theater to experimental fringe theater, from children’s musicals to televised concerts.

Among the scenes that Paller mentions to show the accuracy of the story is one where Amir is debating with his law school colleagues about what is the real law. Is the real law Israeli law or is it Jewish law? The song, which ‘Amir’ sings to elaborate this, unpacks the rabbinic law of din rodef (pursuing the felon), using his fellow students as his actors and staging the debate as an event. This scene underlines the complexity of the situation leading up to the assassination, which involves legal, religious, social and psychological dimensions.

For now, the play is being produced in Jerusalem’s Beit Mazia, which Paller describes as a perfect location. He has booked upcoming performances at Tzavta Theater in Tel Aviv (July 17), HaDofen Theater in Petah Tikva (July 14) and a return to Bet Mazia (July 20), with more shows around the country beginning in September.

How well the play will be received by the wider audience that Paller envisions is in itself part of the issue. Will Israeli audiences, especially the younger generation, be open to this quirky, off-beat production about one of the most disturbing events of Israel’s recent past? Will audiences understand that the controversy that this cabaret exposes is essentially theirs? ■