Pulpits and politics

While some rabbis will draw on the headlines in their High Holy Day sermons, others will completely eschew mention of current events.

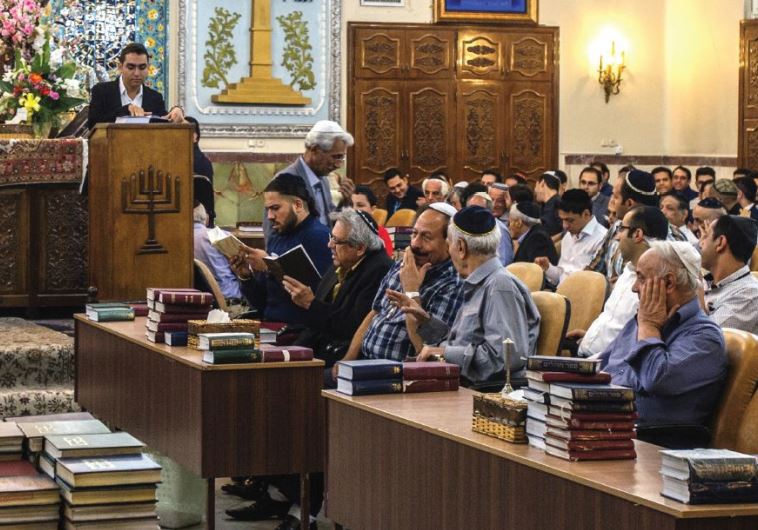

Iranian Jews celebrate Rosh Hashana last year at the Yusef Abad Synagogue in Tehran(photo credit: OLEKSANDR RUPETA / AFP)

Iranian Jews celebrate Rosh Hashana last year at the Yusef Abad Synagogue in Tehran(photo credit: OLEKSANDR RUPETA / AFP)