A (religious) woman’s place

The controversial sentiments about women in the army as expressed by some leading national-religious rabbis recently might indicate a new culture war.

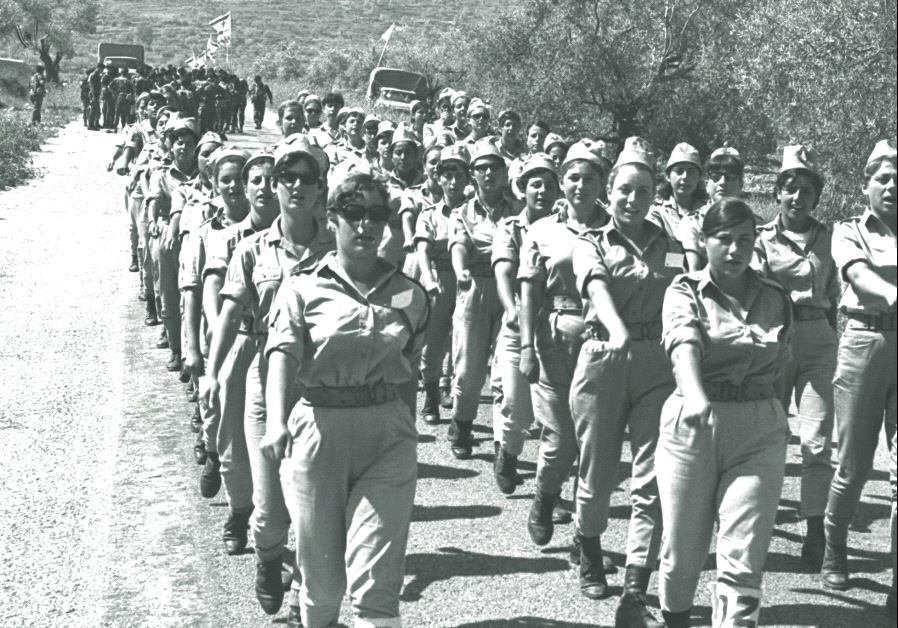

IDF women soldiers marching near Jerusalem, 1969(photo credit: MOSHE MILNER / GPO)

IDF women soldiers marching near Jerusalem, 1969(photo credit: MOSHE MILNER / GPO)