Think About It: Twenty years on

I dislike the term “Rabin’s heritage,” though I believe that Rabin’s assassination in itself has certainly turned into part of the Israeli heritage.

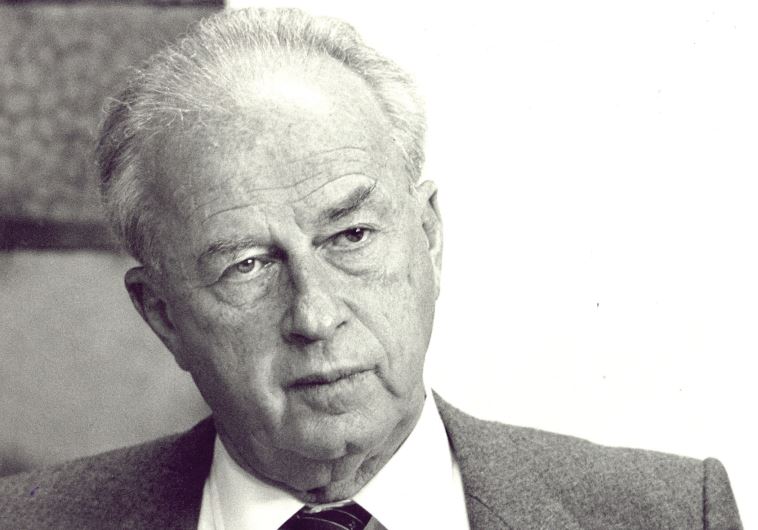

Yitzhak Rabin in 1985, then defense minister(photo credit: DAVID BRAUNER)

Yitzhak Rabin in 1985, then defense minister(photo credit: DAVID BRAUNER)