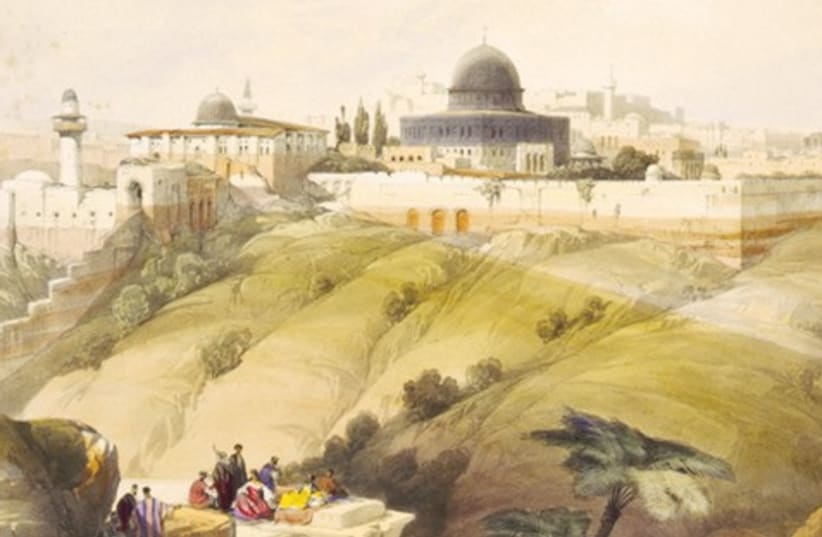

Later, Twain was to compile his twice-weekly reports on his travels into a tome called The Innocents Abroad, the front cover of which is currently on display at the National Library. The “Dreamland – American Travelers to the Holy Land in the 19th Century” exhibition offers a fascinating glimpse of what explorers, pilgrims, researchers and tourists from the States thought of Palestine of the time.Twain is in good company in the “Dreamland “display, with fellow scribe, Moby Dick author Herman Melville as well as feted explorers Eli Smith and Edward Robinson and former US president Ulysses S. Grant. There is also a delightful late 19th-century diary of a trip here kept by a teenaged Theodore Roosevelt, who himself occupied the Oval Office some 23 years later.Mind you, Twain’s expectations of finding a land flowing with proverbial milk and honey might have been fueled by Scottish artist David Roberts’s 1839 pastoral sketches of the Holy Land. But while, publicly, the Scot enhanced the mystique and romance of the landscapes here, privately he expressed an entirely different impression.“I have often laid down my pencil in despair,” is just one poignant description of the artist’s reaction to the squalor and desolation he found here, taken from his eastern journal account, which is housed in the National Library of Scotland, in Edinburgh.“Dreamland” was initiated by the US-based Shapell Manuscript Foundation, which specializes in historical documents from the 19th and 20th centuries relating to the United States and the Holy Land. Many of the items on display at the National Library normally reside at the Beverly Hills City Library in Los Angeles.“This exhibition looks at the Holy Land from an entirely non-Jewish point of view, in terms of 19th-century American visitors,” explains Dr. Milka Levy-Rubin of the Hebrew University’s Department of History. “They weren’t all devout Christians but, once they were here, they all realized they had arrived in the Holy Land.”Considering the lack of basic Western amenities in the Middle East back then, the number of Americans who traipsed over here is impressive. According to Levy- Rubin, technology also lent a helping hand. “Before the mid-19th century, before steamboats started making long voyages, if you headed east from America you were dependent on the winds blowing in the right direction,” she says. “With steamboats you knew, give or take a day or two, when you’d arrive at your destination.”In fact, Ottoman-ruled Palestine started opening up to the West in 1799, when Napoleon invaded from Egypt, and took most of what is now our coastline, as far as Acre. Of more lasting importance was the fact that the first systematic survey of the Levant was undertaken, at the time, by Bonaparte’s engineers and geographers. This produced what was to become known as the Jacotin Map, a copy of which is currently on display at the National Library.“This set off a pattern of modern research and mapping,” explains Levy-Rubin, adding that religion came into the picture here too. “There is scientific and research exploration, based on the biblical texts, which try to validate the stories in the Scriptures.”In addition to reliable long-distance means of marine travel, other technological innovations also had their say in the development of Palestine as an increasingly popular vacation choice. “Trains came into the equation,” says Levy-Rubin. “You could travel here from Turkey and Syria and get around more easily.”Western presence in the Holy Land also began to increase as the Ottoman Empire began to wane, and various Western powers, including the United States and Britain, began to establish a toehold here. After the British sent a well-equipped party to survey and document parts of what is now central Israel, the Americans subsequently dispatched naval commander William Francis Lynch, in 1847, to seek out the source of the Jordan River and explore the region around the Dead Sea.Lynch’s party, in fact, covered much of the route later taken by Twain, which took in Lake Kinneret, the Jordan River down to the Dead Sea, then across the Judean Desert, via the isolated mountainside monastery of Mar Saba and Bethlehem, to Jerusalem. After resting in Jerusalem for a while, Lynch and his group continued on to Jaffa before heading back north to Tiberias and Lake Hula, and thence to Damascus, Baalbek and finally Beirut.The report Lynch eventually submitted to the United States government, entitled “Narrative of the United States’ Expedition,” a copy of which is in the exhibition, includes the first accurate maps of the Jordan River and the Dead Sea. He also brought back geological and botanical specimens and observations about ornithological areas of interest.As the Holy Land became an increasingly attractive excursion proposition, various individuals and commercial enterprises began to exploit the lure of the Middle East. One such was a certain H.A. Dickson, who set up a peripatetic facility which he called Dickson’s Palestine Museum. The blurb for the traveling show attempts to bring in the crowds by proffering “a Collection of Curiosities, Reptiles, Fruits, Stones &e.” It goes on to inform the public that “Mr. Dickson, having had five years experience of Arab life, is better able to give a full description of the manners and customs of that Country, than any one that has merely travelled through it.”In fact, Dickson and his family had lived in Jaffa and had been victims of a brutal attack there, which led to their Stateside return. Dickson was evidently a hardened marketing man and was quick to see the commercial possibilities offered by providing the public with “a thrilling narrative of that awful night.” Around 20 years later, the Holy Land started to become a fixture of adventurous – and no doubt well-heeled – Americans’ foreign travel interests when Englishman Thomas Cook began offering organized “Grand Tours” that took in the Nile and much of Palestine.And the rest is history.

• For more information about the “Dreamland – American Travelers to the Holy Land in the 19th Century” exhibition: 658-5027 and www.nli.org.il