They needed to be there

Over 3,500 foreign volunteers fought in the War of Independence.

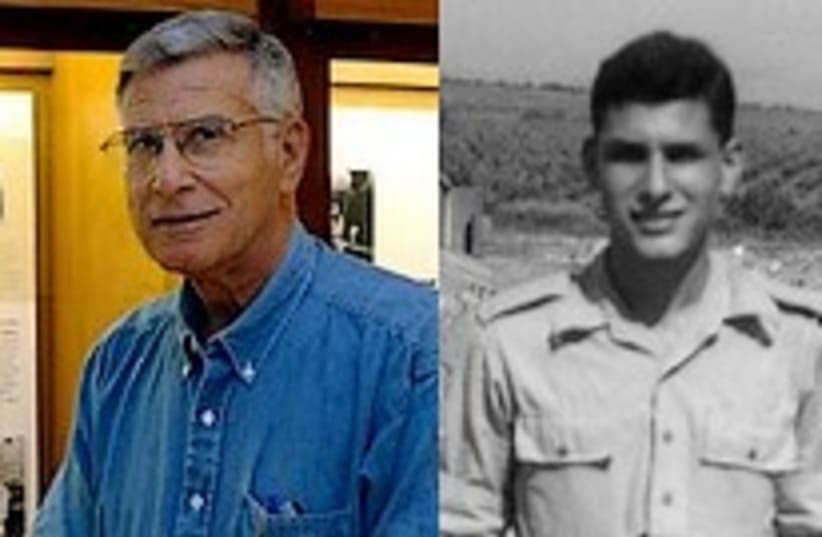

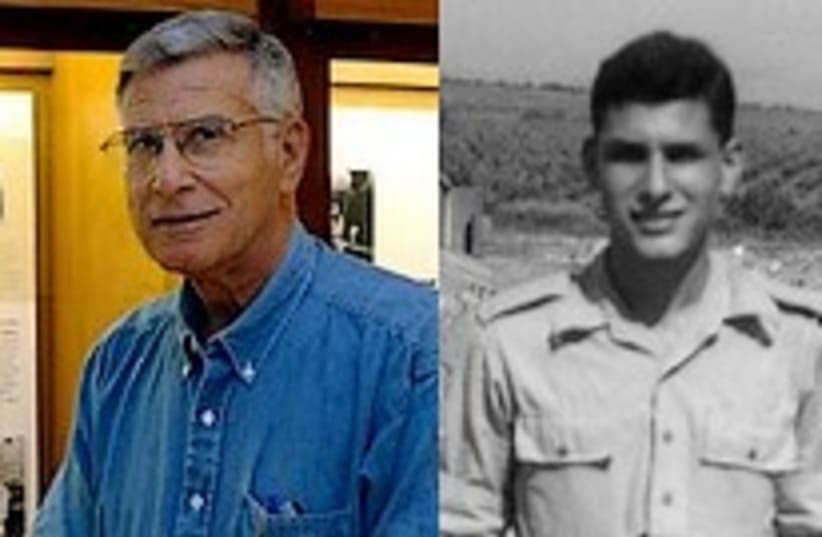

It is 60 years since Ralph Lowenstein finished his freshman year at Columbia University in New York and made his way to a kosher butcher shop in Paris looking to volunteer in Israel's War of Independence.

After a month in England on an exchange program, he arrived in Paris in July 1948. He knew what he wanted to do but not where to do it. "I never knew any French at all; I only knew the word for Jew was Juif," he explains in a telephone interview. "I looked in the phone book and there were only two listings that started with the word Juif. I went by Metro to the first one and it turned out to be a kosher butcher."

After a good laugh at Lowenstein's expense, one of the customers directed him to the newly opened Israeli embassy, and there he signed up.

'It's not a dream'

Lowenstein is one of the 950 Americans and 300 Canadians in Mahal (an acronym for mitnadvei hutz l'aretz, volunteers from abroad) who served in the Israeli army and air force in 1948. Another 240 Americans and Canadians volunteered on the Aliya Bet ships, which brought Jewish refugees to Palestine in 1947 and 1948. (In total, Mahal attracted 3,500 volunteers, according to Smoky Simon, chairman of World Mahal. Simon, a volunteer from South Africa, now lives in Israel.)

As the 60th anniversary of the war drew near, I sought out 10 of the American and Canadian volunteers, or their surviving relatives. I wanted to know why they went, what it meant to them then, what it means to them now.

Like other volunteers Lowenstein had a mixture of motives, but chief among them was his strong Jewish background. He grew up in an observant family in Danville, Virginia; his mother had been a Hadassah president; and the Orthodox rabbi in Danville, with its Jewish community of 50 families, was young, inspirational, and very Zionist. At Columbia he joined the Intercollegiate Zionist Federation of America.

In 1948 he seized the unique opportunity to be present at the creation of a Jewish state. "It was 1776 in this country. No other Jew, even though Jews fought in subsequent wars, like the Six Day War, no one else could ever have fought in a war of independence."

His parents knew he'd gone to Europe but not why. He recalls that when he was about to board a ship carrying 2,800 refugees to Israel, "I put a letter in the mailbox in Marseilles just before I went up the gangplank... My mother nearly had a nervous breakdown. They pulled every string to get me back that they possibly could, but by that time I was in the jaws of a bureaucracy and the army." Within 10 days of his arrival, with no training, Lowenstein found himself in a half-track with eight or nine other soldiers, being shot at by Arabs as they rode to a nighttime battle in Galilee.

"It doesn't take more than a minute or two to realize it's not a [bad] dream," he tells me. His unit was the 79th battalion of the Seventh Brigade, a motorized unit with armored cars, half-tracks and machine guns - but no tanks. Lowenstein became a half-track driver and the unit was dispatched all over Galilee for night attacks. The battalion spearheaded Operation Hiram, a campaign that cleared Galilee of Syrian, Iraqi and Lebanese troops in October 1948. By the end of December, with fighting in Galilee over, he returned to the US. He was back in Columbia for the spring semester.

"I rejoined my class and graduated with my class, made up the work in the summer and most people didn't even know I'd been gone."

The experience, brief as it was, had lasting results for Lowenstein: "First of all a tremendous feeling of self-confidence... I always felt there was nothing I couldn't accomplish." And a lifelong commitment to Israel and to Judaism, a commitment he has done his best to pass on to children and grandchildren. His daughter, a member of the city council in Ann Arbor, Michigan, studied for a year at Hebrew University, is fluent in Hebrew and visits Israel at least three times a year.

Ralph Lowenstein is a retired dean of the journalism school at University of Florida-Gainesville and the author of five books, one a novel based on his experiences in 1948. In recent years he has spent much of his time organizing the Museum Project, an exhibit about the North American Mahal veterans that is located at the Hillel House in Gainesville.

Having collected questionnaires from 500 of them, Lowenstein has a fairly complete roster of these veterans, a task that has been complicated by the secrecy with which the veterans were recruited or volunteered. Despite president Harry Truman's immediate recognition of the new state proclaimed by David Ben-Gurion on May 14, 1948, the State Department remained pro-Arab and anti-Israel. It strictly enforced an arms embargo to the Middle East, and passports of Americans traveling abroad were stamped, "Not valid for travel for the purpose of serving in a foreign army."

'Do you want to help your people?'

Paul Kaminetzky (now Paul Kaye), a volunteer on the Aliya Bet ships, describes an encounter in early 1947 that sounds like the opening of a bad spy novel.

"I come home from the service and I'm getting ready to go to college. I'm working in a record shop and I get a phone call, 'Do you want to help your people?... If you want to help your people be on the corner of 39th Street and Lexington Avenue Thursday at such and such a time. A man in a black leather jacket will come by with a newspaper.'"

If the man drops the paper in the waste basket, go home, you're being followed, the mystery caller continued. If he puts it under his arm, go with him.

"I thought it was my sister, she's a practical joker," Kaye continues. He checked with his sister Millie and his friends, none of whom had made the call. The next day, "I stand on the corner and a guy walks by with a black leather jacket, he puts the newspaper under his arm. I follow him around the corner, as instructed."

The man, Akiva Skidell, got to the point quickly: A ship was about to sail from the US to pick up Holocaust survivors in Europe and bring them to Palestine, in contravention of a British blockade. "Would you volunteer to go over?" Skidell asked. There were risks; the British government threatened up to eight years in prison or heavy fines for those smuggling illegal immigrants.

"I said let's go," Kaye answered. With his background in the US Navy in World War II, he joined the crew of the SS Tradewinds as third engineering officer. Renamed Hatikva, the ship sailed from Baltimore, picked up 1,450 refugees in Italy and steamed into the eastern Mediterranean, where it was stopped by a British warship. All 1,450 passengers and the crew were interned first in Cyprus, then in Atlit, near Haifa. Kaye escaped from this camp, made his way back to New York and a year later volunteered as an engineering officer on another ship, the Pan York. This time there was no British blockade; it sailed into the now-independent State of Israel with a boatload of new citizens.

Why did you go, I ask Kaye.

"We have to go with the dream. It was a dream to me [returning to Jerusalem and Zion]. And to make a state, good Lord, who would have thought? So I said, 'Let's go.'"

'I was filled with rage'

Si Spiegelman was another who didn't tell his parents when he volunteered for the IDF. He was only 18, and his decision grew directly out of his personal experience and the fate of his family in Europe during World War II.

Spiegelman was 12 when he, his parents and sister escaped from German-occupied Belgium in 1941. His father was a successful diamond merchant; he credits his mother with the decision to leave. "She was always very warm and supportive but tough. Tough. That's why we survived. At a time when nobody believed it [what the Germans would do], she went around telling people what was going to happen."

The family got to France and with the help of smugglers whom they paid, crossed the border between occupied France and Vichy France illegally.

"They [the smugglers] got 20 people together and then in the middle of the night we crossed the border. We saw the watchtowers, the machine guns and the search lights. If you were caught, they turned you back to the Germans. I remember it very vividly; it was three, four in the morning; we crawled on our bellies across the wet grass."

Eventually they made it to the US (after four years in Cuba), but most of Spiegelman's family in Antwerp - aunts, uncles, cousins - died in the Nazi death camps. "I can't describe to you [how] I lived after that," Spiegelman said, about learning some of the details. "I was filled with rage, I wanted to do something."

He joined the Zionist youth movement and through an organization called Land and Labor for Palestine, enlisted in the Hagana.

Arriving in Israel in July 1948, he was stationed in the Beit She'an area. Much of the fighting was over by then, and Spiegelman wound up in a small unit guarding a hill called Tel Radra and seeing almost no action - just as well, since his entire training consisted of firing one round with a Sten gun and several more with an old Italian rifle.

Spiegelman went on to an MBA and a career as a management consultant. About the time in Israel he says, "Still I call them the best days of my life. Being part of the creation of the state was a privilege, to have lived in that moment in history. Israel never owed me anything. I owed Israel."

'Especially because of the Holocaust'

During World War II, Mitchell Flint had been a US Navy pilot who had flown many missions over Japan and shot down a Japanese plane. He would eventually become a lawyer and open his own practice in Los Angeles, but in 1948, he recalls, "I was going to the University of California, very active in Hillel... I knew the war was coming and because I was a fighter pilot and especially because of the Holocaust, I decided to volunteer."

Flint got to Czechoslovakia in June 1948, where he trained on the Czech version of the German Messerschmitt (called the Avia) before arriving in Israel where he flew the Avia and crashed one of them ("The Avias had a lot of things wrong with them, they cracked up very easily"). Later he flew Norsemans and Spitfires, bombing Egyptian troops in the Faluja pocket (a place in the Negev that saw heavy fighting), ferrying supplies to Sdom and doing reconnaissance of Syrian airports.

'He didn't ask us, he told us'

Americans and other foreigners were a mainstay of the Israel Air Force in those early months and years. Rudy Augarten had flown fighter planes in World War II, shot down two German planes, was himself shot down over France and captured, but escaped and made it back to Allied lines. In July 1948, after his junior year at Harvard, he traveled to Israel, joined the infant IAF and shot down four Egyptian planes.

Augarten died in 2000. His sister, Tobie Specht, remembers his feelings about the war. "He was determined to go to Israel to fly, he felt he had to." Given the long period during which he'd been missing in action in World War II, his parents were especially upset at his decision. Still, his mind was made up. "He didn't ask us, he told us," she recalls.

Tom Tugend was another vet who felt the tug of Israel. He was studying at Berkeley and got in touch with the business agent in the butchers' union (butchers were apparently destined to play a key role for American volunteers) who had Hagana contacts. He was told, "Sit tight, we'll get back to you," but when nothing happened he went to New York and located recruiters who moved more quickly. "Okay, that's great, can you leave tomorrow?" they asked. In Israel he was part of an English-speaking battalion that fought at the Faluja pocket and elsewhere in the Negev.

'I knew I had to do it as a Jew'

Lou Laurie, a Canadian Navy veteran, had already volunteered and was aboard the Pan York in 1948 when it stopped at a DP camp near Marseilles to pick up Jewish refugees and bring them to Israel. Laurie had been recruited while living and working in Quebec City. When he saw who these refugees were and what they had been through, "I knew I had to do it as a Jew," he says.

In Israel Laurie fought in an English-speaking unit, the 72nd battalion of the Seventh Brigade, a battalion commanded by fellow Canadian Ben Dunkelman; in one of their battles, they seized Tamra Hill, a high point in Western Galilee, in a bayonet charge. In his subsequent career as a photographer, businessman and inventor, he has never forgotten the emotion that inspired him in 1948. It was as if the DP camp "was emblazoned in our minds."

Another of the Canadian volunteers, Joe Warner, was working as a pharmacist-apprentice when the UN partition plan was approved. That night he couldn't sleep. "I was completely sure this was a war that the Jews had to win," he says; if they didn't, "it would be very bad for every Jew everywhere in the world."

Soon he was in New York knocking on the doors of Jewish organizations in an effort to volunteer - and not finding anyone to take him. In frustration he returned to Toronto, where he was promptly signed up by a Canadian businessman recruiting for the Hagana.

Hilde and Max Goldberg met in Bergen-Belsen after its liberation by the British army. Hilde, a Dutch Jew and a nurse, was running a child-care center, first with the British Red Cross and then with the American Joint Distribution Committee. After completing medical studies, Max, a Swiss Jew, "thought he hadn't contributed anything to the Jews and he joined UNRRA, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency," Hilde explains. Among his duties was inspecting Hilde's child-care center to make sure the kids were getting enough milk "and he began to inspect that day-care center more and more," she remembers.

They got married and moved to Switzerland, but Hilde didn't care for the Swiss; she jumped at the invitation from the Hagana for the two of them to come to Israel as medical volunteers. "Israel was very close to our hearts and when they asked us, of course we went," she recalls. They landed in March 1948 and were immediately sent to the front lines, at Mount Gilboa, outside Afula.

Another nurse-volunteer from New York was Naomi Kantey, née Levin ("My parents were socialist-Zionists, I was brought up in that kind of a household.") In hospital she took care of Leon Kantey, a South African who was wounded at Ramle; they were married in Tel Aviv in 1949.

'The only thing I could feel was that we had to win'

Augustine (Duke) Labaczewski had been in the US Merchant Marine during the war and would remain a seaman until the 1990s. Duke, a non-Jew, was a close friend of Mike Pearlstein's; they'd lived in the same Philadelphia neighborhood. When Pearlstein decided to volunteer for Aliya Bet, he invited Duke to join him. Soon the two of them were on the SS Tradewinds, bound for Europe and then for Israel. Duke had a background as a baker and in Lisbon he baked matza so the crew could celebrate Pessah. In Israel he trained with the Palmah and saw action in Galilee, near Tiberias.

When I ask why he volunteered, Duke answers, "I think that when you see six million [Jews] are killed, how can you not go?" During the fighting, he says, "The only thing I could feel was that we had to win, there was no losing there."

Given the attitude of the State Department, volunteers knew that on their return they would face questioning by the FBI. In Europe en route to Israel, they were given new names and new passports so that their passports would not show an Israel entry stamp. Most returned without incident, but the US government did prosecute three men who acquired and shipped weapons to Israel - Hank Greenspun, Al Schwimmer and Charlie Winters.

Greenspun smuggled weapons to Mexico for shipment to Israel. Schwimmer, a TWA flight engineer and licensed pilot, arranged for the acquisition of 15 surplus heavy transport planes, and organized the Air Transport Command that ferried planes and arms from Czechoslovakia to Israel. Ben-Gurion called his efforts "the Diaspora's single most important contribution to the survival of Israel," according to Ralph Lowenstein's Museum Project. Schwimmer and Greenspun were each fined $10,000 and lost their civil rights.

Ironically, the only American actually jailed for violating the embargo was a Christian, Charlie Winters. He sold three surplus B-17 bombers to Israel and was sentenced to 18 months in prison. He wanted to be buried in Israel and after his death in 1984, his remains were transferred to Jerusalem for burial in the Christian Alliance Church cemetery, adjacent to the 19th-century Templer cemetery in the German Colony.

A different generation

The generation of men and women who volunteered in the War of Independence was very different from American Jews today. Some of them knew Europe and their European relatives firsthand, having come to the US as children or teens in the '30s and '40s. Even those born in America grew up with the languages of Europe, especially Yiddish, ringing in their ears. No wonder that the Holocaust triggered in them a mixture of rage and resolve, while the creation of the State of Israel gave them a way to act.

It's no slur, just the plain truth to acknowledge that military service has gone out of style for American Jews. This process began in earnest during the 1960s when young men of all religions (but especially better-educated ones) sought deferments to avoid Vietnam. I was among them; I got a two-year deferment for service in the Peace Corps in Africa, another two years for graduate school and a final, one-year deferment as a New York City teacher.

At the end of March 2008, The New York Times published the names and pictures of 1,000 Americans who died in Iraq in 2007 and the first months of 2008. I scanned the ranks of these men and women for Jewish names. Surely there must have been a few, but I searched in vain for a single Cohen or Goldman or Schwartz or Epstein or Siegel.

Many of the volunteers for the War of Independence came out of World War II, probably the last war in which American Jews served in mass numbers. They had military experience, military knowhow and the self-confidence that comes from having survived in battle. Theirs was a generation that took military service as a matter of course.

The Americans who came to Israel in 1948 were also different from the 60,000 Israelis who served in the war. By 15 or 16 most Israelis, except for the ultra-Orthodox, had already joined the Gadna, the youth battalion of the Hagana. They knew what the new country faced; they were defending their own homes. Moussa Yarconi, born and raised in Jerusalem, told me about traveling on the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem road when it was under constant fire from Arab troops. "Fear?" he said to me about the emotions of such a journey. "Of course, fear, but so what? Jerusalem was our home."

But the Americans who volunteered were not fighting for their homes. They were a tiny fraction of all American Jews. They were less than 1 percent of Jews who served in World War II. They knew the danger but volunteered anyway; 40 of them, 29 Americans and 11 Canadians, died in the War of Independence.

Si Spiegelman puts it this way: "My story is probably not an exciting one. People love to hear about battles and about blood and gore. I did what I was told to do. Had they told me to go to Faluja and get shot, I would have gone to Faluja. But I wasn't told. That's how it works out. The important thing is that we were there."

This month hundreds of Mahal veterans from the US, Canada, South Africa, the UK and elsewhere came to Israel to celebrate the 60th anniversary of independence. For many it will be their last trip. The stories of these men and women in their 80s who at 18 or 22 risked so much - many going off to war without saying good-bye to parents - provide an answer, finally, to my question, "Why?" They came, I think, because they needed Israel as much or more than Israel needed them.

if(catID != 151){

var cont = `Take Israel home with the new

Jerusalem Post Store

Shop now >>

`;

document.getElementById("linkPremium").innerHTML = cont;

var divWithLink = document.getElementById("premium-link");

if(divWithLink !== null && divWithLink !== 'undefined')

{

divWithLink.style.border = "solid 1px #cb0f3e";

divWithLink.style.textAlign = "center";

divWithLink.style.marginBottom = "40px";

divWithLink.style.marginTop = "40px";

divWithLink.style.width = "728px";

divWithLink.style.backgroundColor = "#3c4860";

divWithLink.style.color = "#ffffff";

}

}

(function (v, i){

});