Alternative reality: The 'What Ifs' of Jewish History

A history professor delves into the world of Jewish counterfactual history – like what if Israel had been established in East Africa?

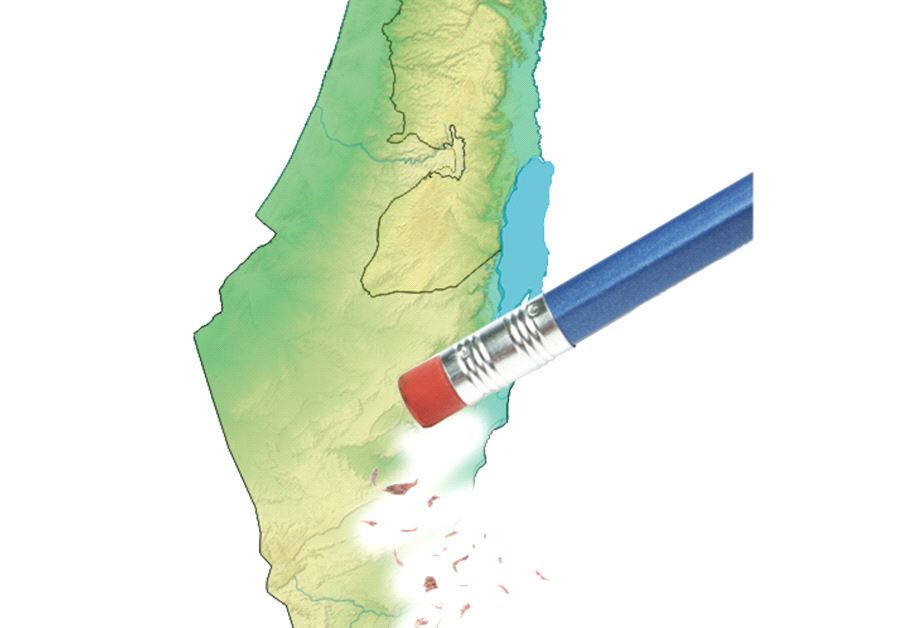

Erasing the state of Israel illustration(photo credit: OLGA LEVI)

Erasing the state of Israel illustration(photo credit: OLGA LEVI)