What happens after genocide?

For a Tutsi survivor of the Rwandan genocide, educating his people about the Holocaust is his own form of therapy.

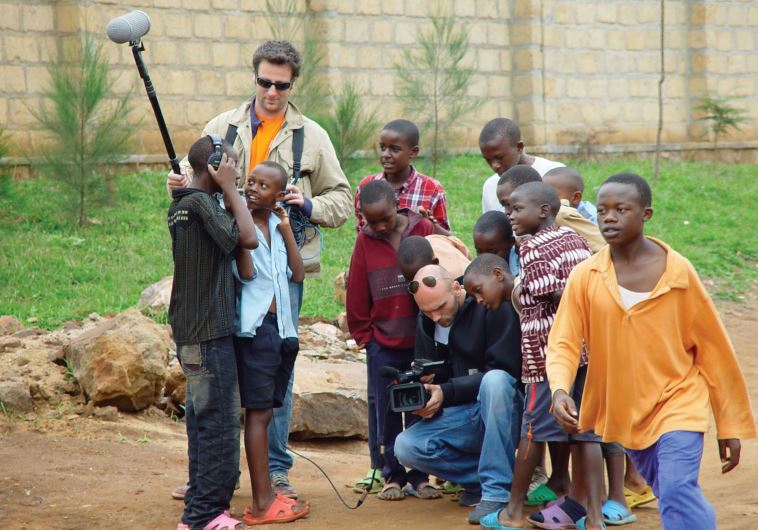

Ygal Egry (crouching) during filming in Kigali with sound engineer Frederic Cristea(photo credit: YGAL EGRY)Updated:

Ygal Egry (crouching) during filming in Kigali with sound engineer Frederic Cristea(photo credit: YGAL EGRY)Updated: