The school year has started, and with it a collection of worries and uncertainties about what awaits us this year in the education system, as long as COVID-19 is still here. Adding to these worries is a continuous feeling that for over a year, our children haven’t really progressed in certain subjects, and that the lack of frontal learning has caused considerable knowledge gaps.

One issue that concerns many parents is homework.

Parents have a significant role in encouraging their children to do homework, study for exams and submit assignments. But this role is more about "what not to do." Let's talk about it once and for all: Should we help them with assignments or are we hurting them more than helping?

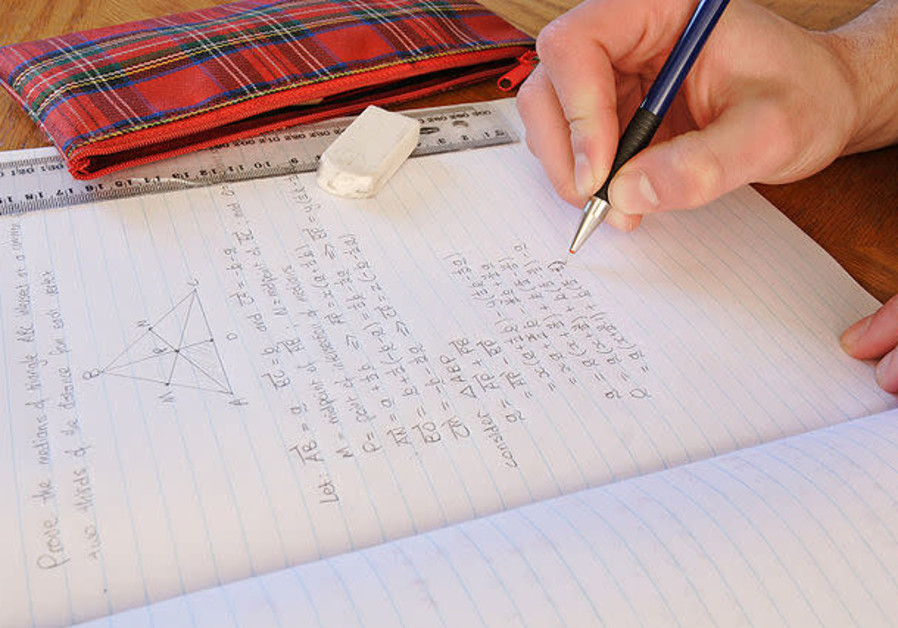

Many parents feel helpless in the face of this great enemy called homework. As children advance from grade to grade, parents become lost in the maze of math exercises they’ve forgotten how to solve, and questions in history, geography and language. Add in the hopeless feelings of parents during COVID-19 - lessons not learned information, tools and skills not acquired, knowledge gaps that have opened up.

What to do?

Parents immediately enlist various private tutors to help their children stay in a good spot in the Israeli rat race.

"No choice" they say, all children are privately tutored - why should my child be left behind?

Why do children even do homework?

Children are given homework that aims to develop independent learning skills. Really, what happens is far from learning, and even further away from independence.

Recently, I was privileged to watch, as a parenting instructor who is also the mother of a teenager in high school, a situation that was very interesting to me. A large group of teens came to our house and saw the book (my daughter's summer reading assignment) on the table.

They piped up: "Wow, when did you start reading? I haven't even bought the book yet.” "I bought the book two weeks ago, and put it in a drawer.” "I actually tried to read, I sat on the couch for two hours and fell asleep. I got to page two."

I smiled to myself as I thought about what their parents would have said if they had heard this chatter.

Let's face it, no matter what we do, they won't read any books this summer, and yet I think they’ll learn a lot just for the sake of it: a lesson in dealing with an unwanted reality.

And so, there will be someone who’ll read the summary, and succeed in creating the impression that he read the entire book, another will use personal magic and make a parent read it and give over the plot. Some will say that he forgot what he read sometime at the beginning of the summer, and a few students will read and maybe even enjoy the book. Either way, it won’t matter what we parents think, say or do. The substance can’t be chewed for them, and certainly not swallowed.

So, what can we do to help our children?

1. Make sure it really is assistance.

What does our child really ask for when requesting help? Listen carefully to the request, and not to what you think is needed. We tend to offer a finger but give a whole hand. How tempting it is to just do it and solve the problem!

It's so much faster and simpler for us, but will it help our child? Connect them to their strengths and help them feel self-sufficient. Ask more questions, give fewer answers.

2. Allow yourself to trust them

It doesn’t always seem that way, and children/teens don’t always give us the feeling that they can be trusted. Still, when we don’t let ourselves get out of the "responsibility" chair and leave it empty at times, our child won’t freely volunteer to sit there.

Once our children understand that we’re here for them, but not in their place, we’ll slowly begin to see them develop a sense of responsibility. Remember it’s a muscle and doesn’t happen instantaneously. It’s a process.

If we show patience and if we trust in their ability to develop the muscle gradually, give them support along the way and express appreciation for their efforts, they’ll develop responsibility.

3. Start when they’re young

Get the kids used to having a natural and logical outcome for every life choice they make. The "price" to pay in second grade is much less painful than the price in high school.

Parents guide kids from when they’re toddlers, giving advice, hugs, support and encouragement. Over the years the solutions are supposed to come from them, and for the most part they are better than the ones we offer. Help them believe in their ability to come up with the best solution.

And no matter how tempting it is to say, please avoid the horrible sentence, "I told you so!" if you offered good advice and they chose another way. Home is our children's safe training ground for their adult lives. Let them "practice."

Experts’ opinions are divided about the importance of homework in students' lives, and yet, we make sure they learn math, history and English, and prepare them for life. Homework isn’t the issue. Let us cultivate in our children a belief in their abilities to overcome any problems throughout life.

Lizzie Porat is a parent group facilitator at the Adler Institute and a lecturer in the field of family studies in the academic track in education and society.