Ongoing efforts to limit damage to the ozone layer, and control the production of ozone-depleting substances have given humans a better chance of surviving a climate crisis, new research has discovered.

The peer-reviewed study, published in Nature Magazine, detailed how climate scientists examined the 1987 Montreal Protocol and the substances which it has prevented the production of since its ratification.

The Montreal Protocol is an international treaty that was designed to protect the ozone layer by ending the production of substances that had been proven to damage it. It has been ratified by 197 countries since its creation in 1987 and has been revised nine times.

Using a modeling framework that examined ozone depletion, climate change, damage to plants by ultraviolet radiation and the carbon cycle, the study explored the "benefits of avoided increases in ultraviolet radiation and changes in climate on the terrestrial biosphere," the abstract explains.

Through examining the modeling framework, the climate scientists discovered that if the Montreal Protocol had not been implemented, the planet would be on track to heat up by an additional 2.5°C by the end of the 21st century.

The current best-case scenario that has been outlined by climate scientists today – based on a current 1°C increase so far this century – predicts that the earth will heat up by 1.5°C by the end of the century, meaning that had the Montreal Protocol not been signed into effect, humanity could have been facing 3.5°C degrees of increased global heating within the next 80 years.

Curbing the production of one particular substance, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), is what has primarily helped give humanity a chance to limit global heating to 1.5°C, the goal set out by the Paris agreement.

Before 1987, CFCs were used in insulation foams, fridges and aerosol sprays in large quantities. Their production was dramatically reduced after the protocols were signed, and they were banned for use in 2010. However, CFC emissions continue to leak into the atmosphere from insulation padding in older buildings.

Although significantly reduced, CFC emissions are still a threat to the atmosphere today, as their unregulated use still takes place in various parts of the world.

In 2018, scientists spotted a resurgence of CFC-11 levels in a rogue insulation production in eastern China, Nature reported in a 2019 study. Upon the confiscation of the materials and demolition of the factory, global CFC-11 levels once again fell to the expected amount.

The research on ozone layer damage was carried out by teams in the UK, US, and New Zealand, and was based on a theoretical rise in CFC use at a rate of 3% a year, starting from 1987.

The teams found that had CFC use continued to rise, the Earth would already be experiencing the worst-case global warming scenarios, which today are only expected to happen if international leaders fail to meet their pledged net-zero CO² commitments.

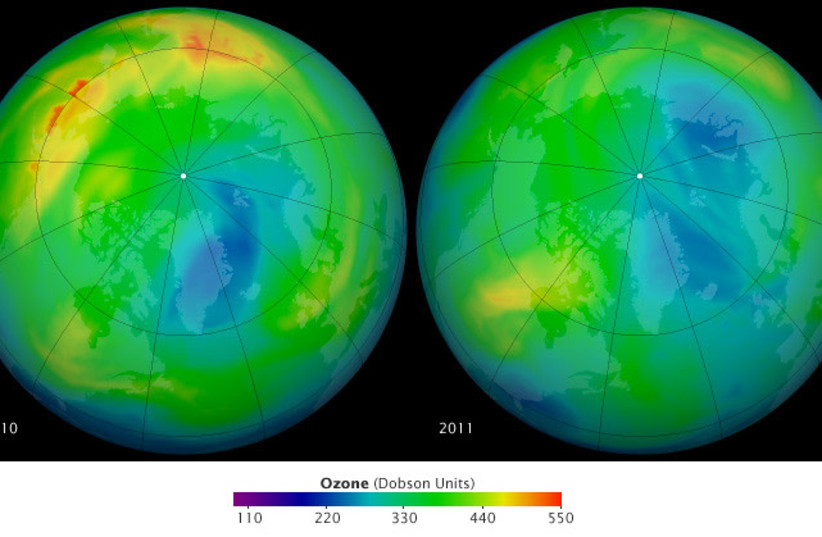

The ongoing depletion of the ozone layer, which protects the planet from ultraviolet radiation, would have meant that the Earth could no longer absorb CO² from the atmosphere, which would have further increased global warming.

Speaking to The Guardian, the study's lead author Dr. Paul Young of the UK's Lancaster University said that "with our research, we can see that the Montreal Protocol’s successes extend beyond protecting humanity from increased UV to protecting the ability of plants and trees to absorb CO².

“Although we can hope that we never would have reached the catastrophic world as we simulated, it does remind us of the importance of continuing to protect the ozone layer."