NUR-SULTAN – Frustrated by endless pros and cons of various fiscal policies presented at a meeting, Harry Truman once famously demanded, “Someone bring me a one-handed economist!”

A similar thought arises almost inevitably when speaking of Kazakhstan. On the one hand, the country appears to be making great efforts to modernize and democratize itself. On the other, the nation has had a sketchy history of, among other issues, human rights, fiscal accountability, corruption and social inequality.

And on an improbable third hand, Kazakhstan shares a 7,644-km. (4,750-mile) border with Russia and a 1,782-km. one with China. As a result, it cautiously occupies a uniquely precarious role in world politics. In fact, when this reporter asked Kazakhstan Ambassador to Israel Satybaldy Burshakov to explain his country’s delicate geopolitical status, he replied simply, “About 7,000 kilometers explains it.”

For the moment, the country enjoys relatively warm diplomatic ties with today’s three great world powers: China, Russia and the United States.

What about Kazakhstan and Israel?

It also shares common interests and close ties with Israel. In fact, it is not unusual to hear praise for the Jewish state. Borat notwithstanding, antisemitism in the country is relatively unknown, as is jihadism. Though the country is 70% Muslim, it is legally and culturally secular. The country’s politicians have been known to brag about how, in developing its capital, it is only “second to Israel” when it comes to having planted 50 million trees.

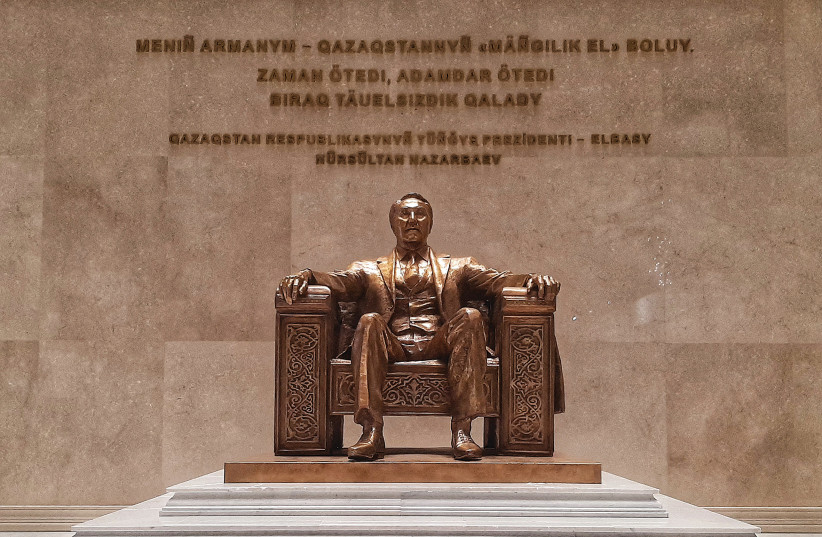

That capital is Nur-Sultan, named after the country’s first president, Nursultan Abishuly Nazarbayev. Though he resigned under pressure in 2019 after 29 years in power, his influence is still felt. Raised and trained in the former Soviet Union, Nazarbayev in many ways symbolizes the clash of old and new.

The capital city is brand new. Design and construction started from scratch on virtually empty ground 30 years ago. Its streets are dotted with architecturally triumphant structures. While today the country often utilizes ancient history to help define its Kazakh identity and a sense of peoplehood, it is striving to become a player in the modern world as a new entity. A voter on Election Day summed it up, saying, “For years our history was imposed on us. Now we define our own.”

Kazakhstan's history

KAZAKHSTAN IS a former Soviet republic, the historical and social implications of which are enormous. Within days of the USSR’s collapse in 1991, Kazakhstan declared its independence.

The transition from a Communist to a more open, free-market economy was undertaken immediately and instantaneously. One might even say brutally. As one government minister explained, “It was very painful, but if you have to amputate a limb, it’s important to do it quickly. The pain will be great, but it will be over faster.”

Other significant factors reverberate until today as a reflection of Kazakhstan’s former place under the Soviet umbrella. Some 600,000 Kazakhs died as Red Army soldiers in World War II; the Soviet Union used its southern neighbor as a literal dumping ground for the massive detritus of Cold War-era nuclear weapons testing; Kazakhstan became a largely unwilling home to some of the cruelest inventions of the Stalinist Gulag; and the country became the forced home of millions of Russian speakers in a Soviet-controlled policy of population transfers.

Kazakhstan is still tied to Russia in significant ways, particularly in defense and quasi-military operations. And the country recently used that connection when the chips were down.

On January 1, 2022, without any prior notice, the price of LP gas in Kazakhstan doubled in response to the lifting of subsidies, an action the government now readily admits was a mistake. Demonstrations against the price increase started peacefully but quickly turned violent.

The government continues to blame unnamed terrorists. Yet even some political activists who helped organize the early demonstrations admit that people with outside interests hijacked the demonstrations. It’s not clear if both sides agree on who those outsiders were.

As the protests became riots and the riots grew in intensity, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev called on Russia for help. With the aid of Moscow, the police/military crackdown was brutal. Activists blame the quick, violent escalation on political frustration. They point to decades of citizen powerlessness and lack of government action to address legitimate concerns. At the same time, the world was barely emerging from two years of the COVID pandemic, and people’s nerves worldwide were frazzled.

Eventually, shoot-to-kill orders were issued. According to Human Rights Watch, quoting the General Prosecutor’s Office, 213 civilians and 19 security officials were killed. More than 4,600 were reported injured and an unknown number were arrested or held for questioning.

In a startling move, under powers assumed by the president, Kazakhstan’s Internet was completely shut down. That created a shock wave whose repercussions paralyzed the economy. Ambassador Bulat Sarsenbayev recalled the period, saying people couldn’t get money from their banks, use apps for payment, travel or conduct business in any way. Although he somewhat sentimentally recalled that his own family was brought closer together because, “When you only have the essentials, maybe a loaf of bread and loved ones around, you see what’s really important.”

It’s unlikely his rosy viewpoint was widely shared. However, once the violence subsided, the government – either forced to respond or genuinely motivated to do so – reacted swiftly. The price of gas was again lowered to its original price, as low as 61 tenge (14¢) per liter, lower than the cost of production. (As a resource-rich nation, Kazakhstan enjoys some of the world’s lowest fuel prices.)

Beyond the brutality, the government also responded with a wide-ranging set of proposed reforms, although politicians take pains to point out that reforms were in development before the riots.

Those proposed reforms were packaged in the June 5 referendum. The referendum itself was a vote on amendments to 31 articles of the country’s constitution, plus an additional two new articles, all told, affecting eight of nine sections of the country’s founding document.

It is a hugely ambitious vision. Some say too ambitious, and beyond the capability of voters to comprehend. Other critics say it is mere window dressing. After all, there have been four major sets of constitutional amendments in the country’s 30-year independent history that have done little to rectify power imbalances, corruption and repression.

Perhaps this time is different, seeing as the current referendum contains proposals far more radical than previous “adjustments.” The newly passed amendments are aimed at increasing citizen representation, limiting presidential powers and expanding the judiciary, all in a meaningful and wide-ranging way, at least on paper.

Skepticism is often a handmaiden to cynicism. It remains to be seen if only one or both of those instincts are appropriate to the current situation.

The referendum didn’t exist in a vacuum. There is also the Ukraine war to consider. Here things get very tricky and there are still more “on the other hands” to consider.

Foreign Affairs Committee Chairwoman Aigul Kuspan raised some eyebrows earlier this month at a press briefing. When speaking of the fraternal nature of Slavic peoples, she said the danger of nationalism is that it can lead to Nazism. In fairness, it should be noted that she was talking through an interpreter, but the translated words seemed to parrot those of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

However, there are strong signals that Kazakhs are just as shocked by Russia’s destructive war against Ukraine. For example, according to a May 17 report in the Russian Vedomosti newspaper, immediately after the invasion began, a major Kazakh ore producer in Rudniy was providing 70% of the ore used by the Russian MMK Iron, Metal and Mining Company, completely cut its supply. As a result, MMK, some 340 km. away, had to shift its source to an ore producer almost 2,000 km. away.

It’s difficult to say if the move was based on solidarity with Ukraine or animosity toward MMK. In any case, the move has certainly complicated business for the Kazakh ore producer.

There are other examples of “other-handedness” in play. However, First Deputy Chief of Staff to President Tokayev said in a March 29 interview with Brussels-based Euractiv media network that Kazakhstan, despite being in the Eurasian Economic Union with Russia, would not “be a tool to circumvent the sanctions on Russia by the US and the EU.”

With the approval of last Sunday’s referendum, Kazakhstan has a rare opportunity to improve the life of its citizens while supporting and promoting peace. It’s okay to be skeptical, but it would be cynical not to wish it well.

The writer was a guest of the Republic of Kazakhstan.