Let no one tell you that city folk can’t enjoy the quiet life. True, on a recent trip to Shaharut, north of Eilat in the southern wilderness of Ovda, we didn’t fall asleep as soon as the sun went down. But we were definitely up with the dawn, in time to watch murky skies fill with streaks of light as a brilliant orange sun rose behind Jordan’s Edom Mountains.

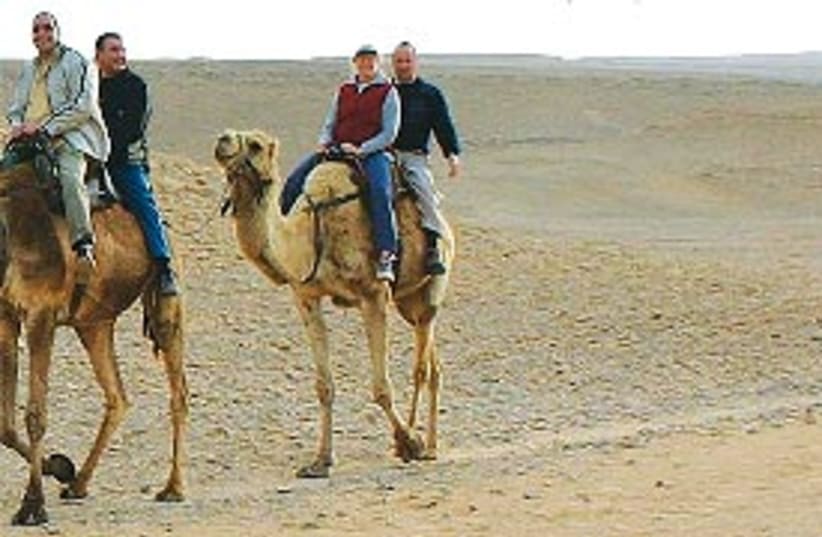

It had been my idea to write about camel rides at Shaharut after friends from Philadelphia told me how much fun it could be. Yet as the day drew near I was petrified at the thought of climbing onto such a large beast — and getting off afterwards! So I planned to watch as my better half mounted and to walk alongside as he rode.

When the time came, however, head guide Yaniv and his assistant Ely wouldn’t take no for an answer and insisted I board Jedid (’new’ in Arabic), a 20-year old male camel. Although Jedid turned out to be a sweetheart, at the time I couldn’t help screaming. Ely chided me gently, telling me that if I hadn’t made such an awful noise, it would have been much easier to mount.

Nevertheless, once on my trusty steed there was nothing to fear. I find horseback riding very uncomfortable, but a camel’s sway more closely resembles a human stride, and Jedid’s legs moved up and down in an elegant gait. Warned previously not to pet his face, in case he became frightened, I settled for patting my camel’s long neck during the trek.

We passed a strange circle on the ground lined with stones stuck deep into the rocky soil; it was one of many in this region. Experts believe that these ancient circles formed worship sites — perhaps, suggests Yaniv, from a time when people prayed to their ancestors.

As long as our path was level, the trip was so easy I could watch the ground looking for the rare plant here and there. Assistant guide Ely picked a small yellow flower from a rare green plant and gave it to me to sniff. It was called scented oxeye, and the fragrance — peaches perhaps? — was heavenly. Ely told me that it was wonderful in tea and is believed to cure headaches, stomach aches, and all kinds of other ills.

The most common plant in the landscape, however, was the bean caper, actually a collection of tiny trees. Some tour guides call the small, succulent leaves Mickey Mouse ears, which they do, indeed, resemble. Bean capers store water in their leaves, and are capable of shedding them in the summer to direct water to their main stalk.

Bean capers can live hundreds of years in a little community that works together to reproduce. But when it comes to competing for survival, it is every bush for itself. That’s why some plants sport green leaves together with dead-looking branches: those that weren’t able to make it.

It was terribly windy, and as we began climbing Mount Shaharut I held onto my glasses with one hand and precariously grabbed the saddle with another. I knew that a camel’s spread-out feet prevent it from sinking into the sand, but this part of our trail included navigation of an ascent that consisted of rocks instead of sand. Nevertheless, Jedid was a real trouper and both of us made it safely to the top of a cliff about 600 meters above sea level. After carefully tying the camels to the rocks, we sat down under a desert overhang, called a znir.

The overhang, and all of the rock in this region, is chalky limestone. Relatively soft, the limestone was created from animal life that thrived under the Tethys Ocean here 200 million years ago and eventually sank to the bottom. Because it is so soft, water pouring down the mountain sides during a flood wears away the rock and creates unusual shapes like the znir.

Mount Shaharut is located within a large nature reserve called Shmurat Metzukei Shayarot, which translates as Convoy Cliffs Reserve. The name has a double meaning: the terrain is hamada, a special desert landscape which is largely barren and sports hard rocky cliffs. It also refers to camel caravans that passed through this area for thousands of years. Indeed, as late as the 1980s Beduin women led camels on an ascent through the Shaharut Mountains to the springs at Yotvata.

When these caravans returned in the afternoon, with camels carrying jars of water on their backs, they would look back at the twists and turns in the ascent and see their own shadows. That is probably why the ascent was known as nakeb a dil in Arabic (Shadow Ascent).

Today it is called as Ma’aleh Shaharut, and it could be clearly seen on the mountains to our right. Some of the camel caravans on the ancient Nabatean Spice Trail, over 2,000 kilometers long and stretching from India and Arabia to the port at Gaza, also traveled the ascent.

Across from us, in the setting sun, we could see the Arava. A narrow strip eight to 10 kilometers wide and 175 kilometers long, the Arava stretches from the Dead Sea all the way down to Eilat. It was fashioned as part of the Syrian-African rift, a gigantic fault line running from Turkey to Uganda. Incredibly intense tectonic forces pushed the ground down — creating the Arava — and at the same time raised mountains parallel to the rift. The mountains of Edom on the rift’s eastern side are especially striking, for they rise steeply to a height of up to 1,500 meters.

At the time, Jordan’s mountains and those in Eilat were part of one huge mountain ridge. Ever since the split, the granite mountains in Jordan have moved steadily northwards — one to two centimeters a year for the last 25 million. Thus the mountains that should have been across from where we sat, now faced Kibbutz Ein Yahav to the north.

Patches of green in the Arava we saw before us were the kibbutzim Yotvata, Grofit, Ketura and Lotan. Lotan is very ecology minded, and runs workshops for working with mud, botanical gardens and recycling. Delicious watermelon from Arava settlements start the season; farmers also grow wonderful peppers, onions, melons and dates — including a special species called majul that can thrive in saline soil and are sold at an excellent profit in Europe. Yaniv told us that Israel’s expertise in growing on saline soil agriculture is shared generously with the Jordanians. Far across from us, we see the Jordanian village of Rahme.

Piles of limestone in hundreds of different shapes, from curlicues to flattish tops to designs only the hand of nature could create, were spread out before us. Jordan’s granite hills glowed with a deep red sheen in the afternoon sun, and minerals in the limestone and sandstone that stretch from Jordan to Israel turned the rocks a dozen different hues.

And then, it was time to leave.

I was delighted to be returning by camel and was the first to reach their tethering site — only to find the animals gone! They may have gotten tired of waiting, or perhaps they were thirsty (they can smell water dozens of kilometers away) and had managed to get away. We saw them in the distance, walking back to Shaharut. As we followed in their tracks, we picked up the blankets they had thrown off their backs, one by one! Jedid was too embarrassed by his behavior to talk to me when we returned about twenty minutes later (it takes far longer to camel trek then to walk), but I blew him a kiss nevertheless.

The large khan (inn) was hosting a group of soldiers, so we feasted on magluba (slow cooked chicken, rice and vegetables) in the smaller one. There were also plenty of salads made of fresh vegetables, some grown right at Shaharut.

Our dinner companions were a dozen young people, post army, who were walking different stages of the Israel Trail and who had met at overnight campsites.

Then it was time to head to our shack, a kind of pseudo-Beduin dwelling called a husha. (I’m told the word husha is a derivative of the Arabic term for ’sheep pen,’ but despite having to bed down on mattresses on the floor, our hut was very attractive with a thatch-covered porch. The toilets and showers are located in a pretty communal building and very, very clean.)

The lights went out when the generator turned off at 10 p.m. and we were up with the dawn. Finally, before we left, we enjoyed a wonderful, desert-type breakfast: light, healthy and filling.

Phone: (08) 637-3218 Camel rides 1-2 hours: NIS 75 adult, NIS 60 child. Dinner: NIS 60/NIS 45. Overnights include dinner and breakfast. Khan: NIS 180 per person; husha: NIS 480 per couple; guest house: NIS 500 per couple.

In the area:

On your way back to civilization, take your family for some nature fun on the dunes of Wadi Qasui, gigantic mounds of clean soft sand that are a stunning sight in the desert. The dunes have long, long ripples from top to bottom, wave-like lines formed by the wind and best viewed in the sun. Run up and down, or roll from top to bottom — what an absolute, thrilling treat!

To get there, leave Shaharut Desert Tourism, and turn right. Continue on this road about four kilometers and turn right at the T- Junction. On the right side of the road you will begin viewing some strange stone remains. Archeologists doing research in this area prior to construction of Ovda Airport a few decades ago discovered numerous ruins that included remains from houses, monuments and worship sites. Some dated back to the Neolithic period, 9,000 years ago, but most were Chalcolithic (4,000 years later).

Soon after you pass the last of the ruins, you will see a sign on your right that reads Tzukei Shayarot Nature Reserve. There is also a faded red trail marker and a pile of stones next to the road. Follow the dirt road all the way to the dunes, where you sure to have a blast.

To reach Shaharut Desert Tourism, travel to Neot Smadar on Highway 40, then go south on Highway 12. Follow the signs.

Shaharut Desert Tourism

Shaharut Desert Tourism is run by Yonatan Bergman, a complex character who combines a love of simplicity and nature with city knowledge and experience. The site does not pretend to be a Beduin tent encampment, as some do, but instead combines desert peace and a few modern amenities. Overnight lodgings are of three types: huts like ours, an actual room with beds and adjacent facilities, and mattresses on the floor of the largest khan, which is separated into personal ’rooms’ with curtains. Camel trips can be individualized: I like to learn about flowers and animals; you may want to focus on another aspect of the desert.

| More about: | Philadelphia, Ovda Airport, Ein Yahav, Jordan |